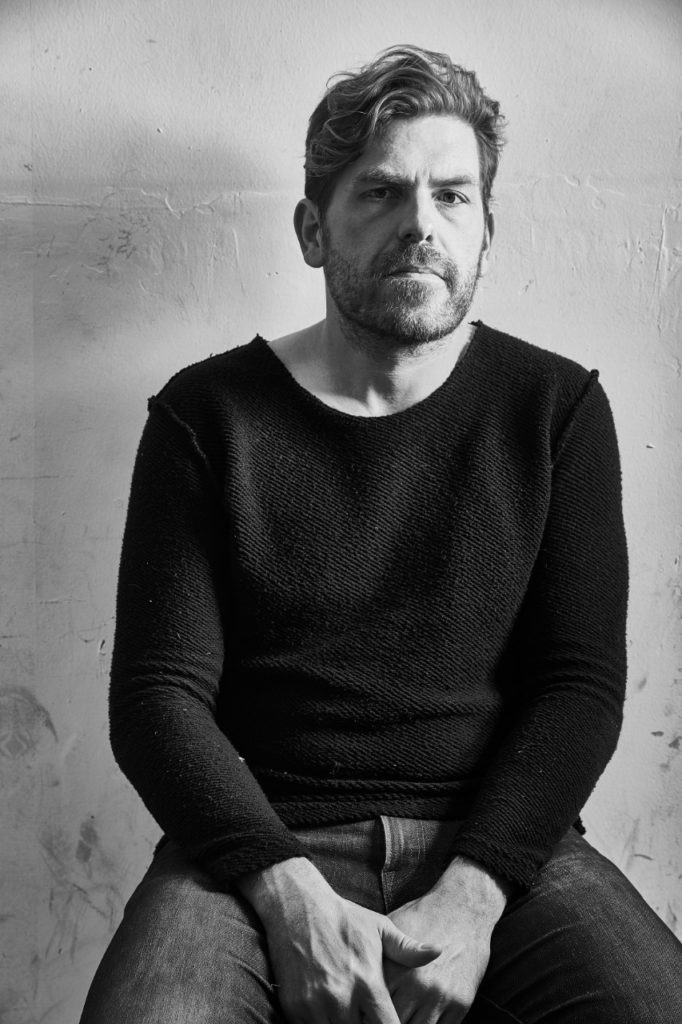

The last time I spoke with Ted Hearne was in 2014; the subject was The Source, his collaboration with Mark Doten inspired by the work of whistleblower Chelsea Manning. Now, Hearne has returned with a new album, Place — a collaboration with Saul Williams, in which Hearne addresses questions of gentrification in Brooklyn’s Ft. Greene neighborhood. It’s a work that involves countless vocalists, found audio, and a complex structure; it also involves moments of sublime beauty. I talked with Hearne about the genesis of Place and how he developed the themes contained within it.

There’s a moment in “Hallelujah in White” where the music briefly shifts into an ecstatic pop register. It’s one of many moments on Place where your handling of genre (and genres) feels particularly expansive. How did the stylistic variety of this work come about?

Thank you! Yes, the music is a kind of stylistic patchwork. This is true of many of my pieces, but in Place there are some strong left-turns in style that directly contribute to the sense of conflict or dialogue happening within the text.

The musicians on this album each come from their own place, and those different origins are, of course, reflected in their different approaches to music. I wanted to find a way of coaxing those approaches into a bulbous and wild bricolage. Audre Lorde says that difference “must be seen as a fund of polarities between which our creativity can spark like a dialectic,” and that image of hers was an inspiration in this process.

The piece deals with appropriation of style, drawing attention to a sort of displacement and gentrification that may occur in music. This is seen in Hallelujah in White: This poem references the Hallelujah Chorus from Handel’s Messiah (a crown jewel of the vocal/classical repertoire but also a piece with personal associations for me because my mom was involved with a Baroque music ensemble when I was growing up in Chicago.) The ecstatic pop-gospel register you mention comes directly from working with the astounding vocalist Isaiah Robinson who is a longtime collaborator of mine, but the use of stylistic signifiers (not just in the vocal register but in the rhythms and interpretation of the music) are meant to work with the conflicts and questions at the heart of Saul’s poetry.

Can the societal hierarchies and patterns that influenced the creation or reception of music be separated from the music itself? Are the same ideologies responsible for structures of systemic racism — redlining, displacement, housing insecurity — inextricably embedded in a piece like the Messiah?

You collaborated with Saul Williams on Place. What was that process like, and how was working with him different from your previous collaborations with other artists?

Saul Williams is one of the smartest and most inspiring artists I’ve ever met, let alone worked with, and it was a total honor to put together this piece with him. I’d been a fan of his since his 1998 film Slam, and Saul has been confronting issues of gentrification and corporatization through his work for decades.

I met Saul while working on a piece with him and the Mivos Quartet as part of a collaboration on the incredibly omnivorous Liquid Music series up in the Twin Cities. We hit it off, and I Ioved how he approached our collaboration with both openness and committed specificity. I asked him to work with me on Place because, well, I wanted the chance to set more of his brilliant poetry, but also because like me he had spent formative years in Fort Greene, and like me he had since moved to LA. I thought it would be interesting to see how our personal cartographies drew the same places differently, and was excited to think about the ways these maps could be represented in music.

Our process of writing Place became the form of the piece. I started by writing text for the first part, and then Saul responded/reacted to what I gave him with the text for the second part. After I wrote music for both parts and we workshopped the material with the musicians, we put together the third and final part together (also with text by Saul). It was a new and invigorating process for me, because instead of composer+librettist collaborating to form one cohesive vision, it was essential to this piece that the identities of composer and librettist remained distinct, because we were talking to each other.

Also, Saul’s impact on the piece coming into fruition was vast and went beyond the usual scope of a librettist. Along with Patricia McGregor, who directed our first production at BAM, Saul played an important role with the singers and instrumentalists who were performing the music, provocative and inquisitive with questions and challenges, and continuously interpreting and re-interpreting his words throughout the process, always finding new ways to contextualize our decisions in the present moment. His background as a performer and musician helped with this as well I’m sure.

Listening to “Interview,” one hears what sounds like a collage of audio from numerous sources. How did you arrive on these particular excerpts — and this particular approach?

When we were starting work on this piece, the director Patricia McGregor sat down with an interview with me about the project. Looking back at the transcript, I was shocked at the incomprehensibility of my own responses to her questions! Even basic questions about why I was drawn to the topic of place, or my own experience living in Ft. Greene, stumped me and I couldn’t find any meaningful words in response. This spoke to a type of paralysis.

The track “Interview” is about questioning the ways I was raised to conflate my whiteness with neutrality, and beginning to confront how generations of racism and privilege may be an inherited force on the day-to-day interactions that govern even my most personal relationships. A question of the impact of whiteness on identity. And then a total sense of unknowing in terms of what comes next. I was reminded of the writings of Eula Biss, a favorite essayist, who has said of her coming to grips with her inherited privilege, “I am wholly aware of my partial understanding.”

I wanted to find a way to portray my own inability to find language about this idea, so I turned to music alone, and made a collage of samples from music that was very important to me growing up. And of course there’s so much cultural and political information embedded in samples. In a way, it’s a blueprint of my personal identity, more than I could ever communicate in words.

You’ve discussed gentrification, and your own involvement in that, as being one of the themes of Place. Has the process of composing this — and now getting this album out into the world — had any effect on that?

The process of making this piece changed my own perception of my role in gentrification. It changed my understanding of gentrification itself — what I had thought of as a cause of displacement I now see as a symptom of larger forces. ‘Gentrification’ is one surface-level step in the pattern of a privileged class exerting their will on everyone else.

I feel more culpable, more complicit, than ever before. But I don’t know if writing toward this theme had any effect on that or not. I think these are complex questions that I will probably struggle with for the rest of my life, especially as I raise white children in the world. And that’s part of the work, isn’t it?

To what extent do you think the concerns you raise on Place are specific to your own experience, versus being more broadly applicable?

The first part of Place is a memoir. It’s about what it means as a white person to see the personal through the lens of the political. And it’s from the point of view of me, lying in bed with my young son, in the midst of a divorce, not being sure where I will live. It’s an experiment in confronting the whiteness that was a part of my identity all along, even when I had the privilege not to look for it. How much of that not-looking is part of what I learned generationally, and how much of it will pass down to my son?

But the second part of Place, with text by Saul Williams, is a rejoinder. No matter how woke or well-meaning, there’s a circling narcissism in the whole project that takes up space, and contributes to the same generations-old centering of the white male protagonist. In this second part, there is suddenly more space between the text and the music — Saul wrote words in response to my words, and then I wrote music setting those words. This dialogue then becomes the conversation of Place.

Numerous vocalists can be heard on Place, creating a sense of dialogue — sometimes very literally. Were there any challenges for you in reflecting the spirit of a productive dialogue in the spirit of this work?

The six vocalists featured on Place are truly incredible artists, each distinct in terms of their own musical background, but they’re all so open to experimentation and flexible in their approach to new work that my job writing for them was relatively easy.

But it was a challenge to figure out how to divide their singing roles, and how to unfold their voices as the music progressed. I wanted to allow every singer to communicate the richness of their unique perspective, while preserving the sense that this couldn’t be possible if the story was told through the self-reflection of the sole white singer (Steven Bradshaw). He needs to take up a lot of space at first, to then be de-centered by the other singers.

So I ended up giving Bradshaw the bulk of the lead vocals in Part 1, with four singers (Sophia Byrd, Josephine Lee, Isaiah Robinson and Ayanna Woods) formed as a choir of sorts, who mostly sing together but sometimes branch off for solo moments. The sixth singer, Sol Ruiz, is left completely outside the narrative, but fires back at the start of Part 2. From that point forward, the other singers each branch in different directions, which creates a texture that’s much more colorful, occasionally bordering on cacophonous. I feel like that type of patchwork — where musicians’ roles are always in flux, where the breadth of performers’ individual identities is honored to the point of unruly overlay — is often the most expressive analog to our daily life.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.