Sometimes it’s the absent things that affect me most. But then, what does absence mean? As I write this, I’m alone in my apartment, surrounded by absence, and yet a whole array of nominally absent people, places, and things preoccupy my mind. Some are friends and family I spoke with yesterday; others are spaces that have long since been demolished. Maybe, then, this is the key: the line between presence and absence is no line at all. It’s a matter of perception, or of definition.

When we walk alone, we’re rarely alone: We have conversations in our past that we mull over in our present. We have imagined dialogues and remembered faces. Consider the way the title character in Saul Bellow’s Herzog composes letters he’ll never send to public figures and intellectuals. It’s as bold a delineation of this solitude and non-solitude as I can imagine. At our best or at our worst, we’re surrounded by the wakes of the people we know. Even so, that absence can be difficult to imagine, or to convey.

Something I’ve always admired are the handful of books that have attempted to evoke this through a precise marriage of prose, perspective, and structure. Michael Kimball’s Dear Everybody is, perhaps, the best example I can think of: It’s a collection of remembrances of a man who’s taken his life, assembled and arranged by his brother, who otherwise remains absent from the narrative. The surviving brother manages to be a presence simply through some of the narrative decisions that he makes, and the information that he reveals and opts not to reveal.

There’s a similar aspect found in Jami Attenberg’s Saint Mazie, the character of a documentary filmmaker whose investigations of New York’s history provide a narrative segue into the Depression-era narrative that occupies most of the book. Here, too, an absent character makes a mark on the arc of the book; here, too, that gulf between presence and absence is alchemically rendered into something mysterious and compelling. I’ve tried something like that myself, in a section of a novel that may or may not work. It’s one of the handful of ways that one can get at the fundamental unknowability of others; at least, it’s one of the handful of ways one can try.

***

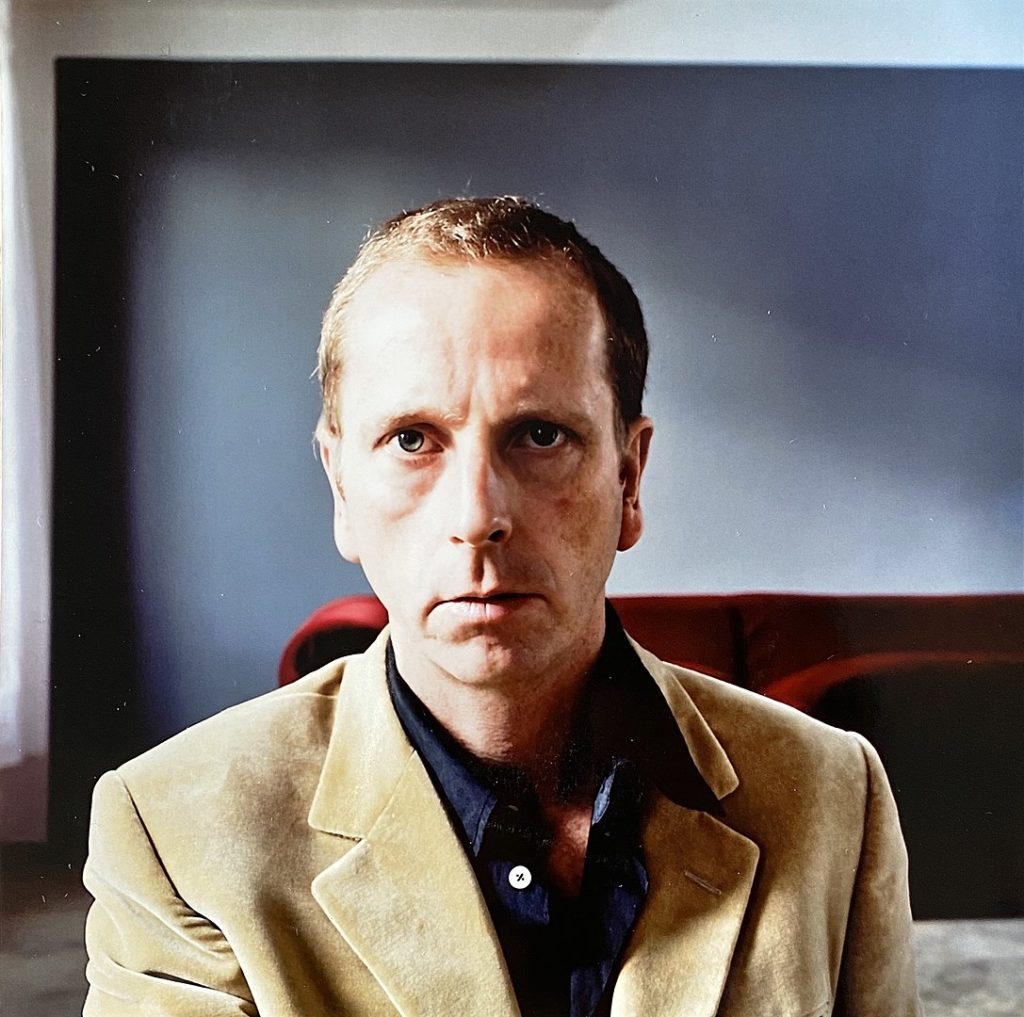

I never read any of Édouard Levé’s books during his lifetime. The English translations of his four books (from the French in which Levé wrote) were published after his death in 2007. In recent years, I’ve read all of them; what’s emerged is some of the most powerful writing I’ve ever seen on alienation, and some of the most powerful literary evocations of absence and presence I’ve ever read.

Levé is equally known for his work as an artist, and two of these four books, 2002’s Works and 2004’s Newspaper, follow rigidly conceptual guidelines which rigorously explore certain things, whether they’re theoretical art projects, news reports, or the life of a powerfully depressed man. There’s certainly a literary precedent for that: in his long essay in The End of Oulipo?, Scott Esposito cites Levé as potentially being “one recent French author who most exemplifies Georges Perec’s philosophy of exhausting a subject.” But Levé’s background in art interacts with his knowledge of literary movements in unexpected ways. Works is a series of 533 different potential art projects, which range from the whimsical (“64. A winter coat is made out of glowworms.”) to the detailed (“83. An artist paints the names of artists he knows on a canvas:,” which is followed by a massive list from Abelléa to Zurbaran) and arcane (“291. Dropped from the thirtieth floor, a camera films its fall.”). Some of the descriptions stretch across multiple pages, while others feel like potent aphorisms as much as potential artworks.

Newspaper is exactly as its title suggests: a series of short news stories, corresponding to the sections of a large metropolitan newspaper. Here, too, there’s a blend of irreverence and a deeply-felt pain. The sections abound with violent crimes, where people in positions of power abuse their authority and devastate the lives of those around them. But within the “Entertainment Guide” section, Levé describes several films, including one that sounds not unlike the 2001 Jet Li vehicle The One–which is not exactly something you’d expect to see alluded to within a work of conceptual art.

It’s when we get into his two later books, 2005’s Autoportrait and 2008’s Suicide, that this sense of absence and alienation becomes tremendously powerful. Almost overwhelmingly so: as translator Jan Steyn notes in his afterword for Suicide, Levé turned in his manuscript and, ten days later, took his own life. Steyn points out that the knowledge of this act when reading this book, and the questions it poses to its central character, makes it impossible for readers to “avoid projecting Levé’s questions back onto his own choice of death.”

Both Suicide and Autoportrait use very clear literary devices to evoke something universal. Autoportrait is composed of one long paragraph, in turn consisting of declarative statements. Some of these are bittersweet or candid: “I like slow motion because it brings cinema close to photography.” Others are wholly aware of the work in which they reside: “I am inexhaustible on the subject of myself,” which falls about halfway through the book. But there’s also this strange sense that comes with the candor with which Levé writes: to what extent is this an accurate portrait of its author?

There’s a device that’s cropped up multiple times in science fiction narratives in recent years–both the Black Mirror episode “Be Right Back” and the Battlestar Galactica spinoff Caprica have used it–focusing on the idea of reconstructing the deceased via their social media profiles. But even the most avid users of social media aren’t completely candid, which leaves an implicit question of how these absences define us. Anne Garréta’s Not One Day works within a similar space, overlapping absences and the personal; it contains a host of personal vignettes, but also reveals that at least one of them is entirely fictional.

Autoportrait was published in France in 2005; Garréta’s Not One Day was published there in 2002. There’s something unsettling about how both authors channel the same questions of veracity and unknowability that might arise after staring at one’s smartphone screen for too long. In Mother Night, Kurt Vonnegut famously wrote, “We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful about what we pretend to be.” For Levé and Garréta, that gulf between reality and pretending is the raw material for something less fearsome, something abounding with potential.

For Suicide, that incorporation of unknowability into the prose is heightened. Here, the book’s narrator addresses the book to a long-dead friend; many sentences begin with a use of the second person, and there are echoes of Autoportrait’s structure throughout. Many of the sentences here are also declarative: “You were such a perfectionist that you wanted to perfect perfecting.” But even when its central character’s suicide is not directly alluded to, its narrative weight is felt.

The range of actions and mental states described within Suicide pulls this book out of the realm of realism, arguably. At one point, the narrator describes a series of dreams that “you” has had. The narrator’s comprehensive knowledge of his subject’s everyday life goes above and beyond that of a loyal friend or biographer; instead, it’s almost telepathic. Unless one wants to read the narrator and the “you” of this book as two sides of one mind, two imperfect halves with the narrative spark emerging out of their discontinuities.

***

Absences can trip you up in another way. They depend on trust in the narrator, that this version of events, even with its absences and elisions, is reasonably accurate. In the case of Levé, the candor of Autoportrait requires an implicit belief that these events and observations are true–that this is, in fact a perspective which one can trust. They depend, in other words, on the presence of a reliable narrator.

In these matters, I have not been an entirely reliable narrator.

I never read any of Édouard Levé’s books when he was alive; that much is true. But those weren’t the only creative works Levé made. In the late summer of 2006, I traveled to four countries in northern Europe; along the way, I spent three days in the city of Helsinki. Helsinki was a little bit of a bust, honestly: I was traveling alone, and in most of the cities where I stopped that solitude didn’t feel overwhelming. In the case of Helsinki, it did. I walked awkwardly around the city’s streets and drank mediocre coffee. Upon my return, I pondered taking a number of the photographs I’d taken, interspersing them with narrative text, and turning them into some sort of short film.

For the record, that project now resides unmade in my own personal version of Works.

There was one clear highlight, though. I spent a day at the city’s contemporary art museum, Kiasma. The experience was tremendously affecting for me–so much so that one of the characters in my novel Reel is named after the museum. At the time that I was there, the museum was hosting ARS06, a group exhibition subtitled “Senses of the Real.” The most striking work, for me, came from Berlinde De Bruyckere, whose sculptures evoked unmade or unfinished animals, the organic and the impossible converging. But she was far from the only artist with work represented there.

Another of the artists with work in ARS06 was one Édouard Levé.

I will confess here that Levé’s art didn’t make an immediate impression on me. When reviewing the catalog of the show years later, I saw his name and realized that, yes, that was the same guy. Perhaps it was my lack of familiarity with the work he was referencing: the project on display, Transfers, involved contemporary re-creations of art from the Tours Museum of Fine Arts. I was unfamiliar with those works quoted; they were cover versions of songs I never heard, and so I had only an absence for comparison. Still, I was there; still, I saw this work.

It seems fitting, then, that Édoard Levé has been an absent presence traveling alongside me.

There are few authors, few artists, more suited to it.

Photo: Desamorais.v – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=104851877

This essay first appeared in Entropy.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.