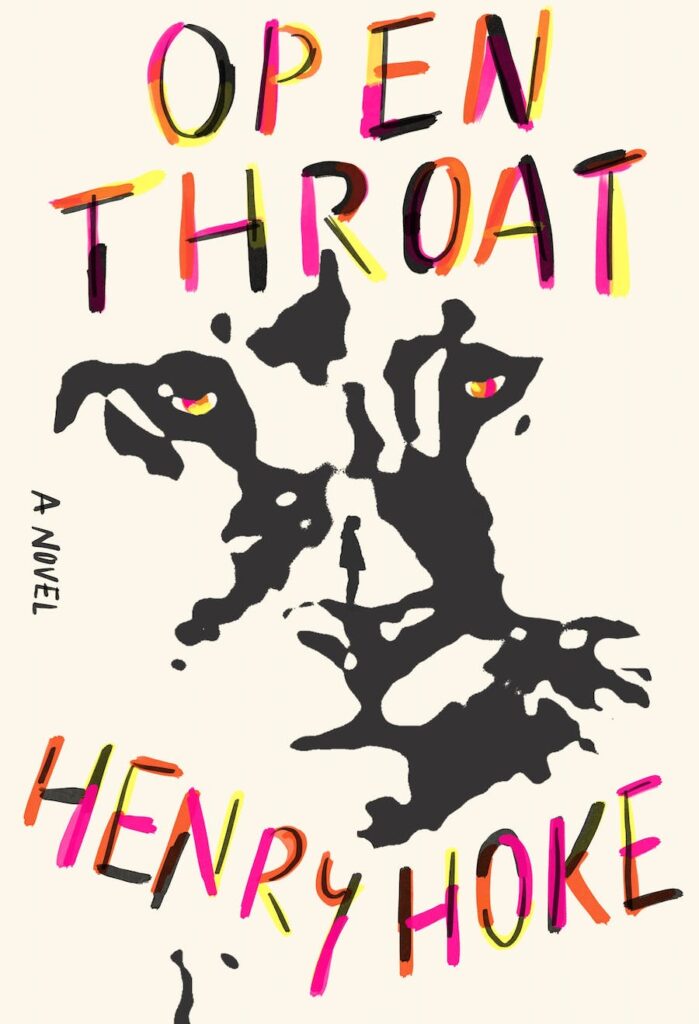

For almost as long as writers have been creating works of fiction, some have dared to imagine what non-human animals might have to say. Paul Auster’s Timbuktu is told from the viewpoint of a dog; John Hawkes’s Sweet William: A Memoir of Old Horse has an equine narrator. And who could forget the sections of Irvine Welsh’s Filth narrated by a tapeworm? It’s into that esoteric company that Henry Hoke comes with his new novel, Open Throat, told from the point of view of a mountain lion in Los Angeles — or “ellay,” in the sometimes fractured syntax of its narrator.

That’s not the only way in which Hoke reminds readers that the novel’s protagonist isn’t human. The mountain lion narrates the book in a series of sentence fragments, with little punctuation; it creates a sensibility that’s situated somewhere between free verse and the ever-popular “this novel is one long sentence” ethos. Though written out, that could make Open Throat look more intimidating than it is; the tone here is wryly comic, with a memorable opening sentence (fragment): “I’ve never eaten a person but today I might”.

Those nine words speak volumes, telling the reader plenty about both the narrator’s potential for violence and their general sense of anomie. In one sense, the novel that follows is about the conflict between those two impulses, as the narrator encounters humans friendly and otherwise, but also seems perfectly happy to remain relatively isolated, occasionally hunting an animal or snacking on a dead one. (In what I decidedly hope is an homage to Grouper, the lion at one point literally drags a dead deer up a hill.)

Open Throat follows an episodic structure, following its narrator as they interact with the residents of a tent city (“I’m the secret member of town,” they think), eavesdrop on humans wandering through the woods, and thinks back to its emotional and physical bond with another mountain lion, referred to only as “the kill sharer.” That last phrase is one one of several ways Hoke reminds the reader of the narrator’s perspective on the world; their description of cars as “loud metals” and of the highway as “the long death” are two others.

Gradually, these different threads come together; one of the humans the narrator sees early in the book carries out a shocking act of violence against the tent city. The narrator is also haunted by memories of their father and faces dangers from the natural environment as well — the mountain lion’s attempts to survive a flash flood make for some of Open Throat’s most gripping passages.

As the novel reaches its conclusion, Hoke ups the stakes in several ways, including riffs on theme park consumerism, internet fame, and mythology itself. The narrator makes a new friend who dubs them “heckit” — a nod to the Greek goddess Hecate — which adds an air of archetypes to the proceedings while also introducing the divine into the mix. Or, as the narrator states, “if you feel alone in the world/ find someone to worship you”.

Some of the human interactions that are mysterious to the mountain lion will be more familiar to this novel’s human readers, meaning that Open Throat can read at times like a stealth novel of circa-now Los Angeles. This feels in keeping with Hoke’s other books, which take big structural risks in unexpected ways: The Groundhog Forever is a time loop story about time loop stories, while Sticker uses a series of stickers to interrogate Hoke’s life, family, and hometown. That said, most great L.A. novels don’t feature the protagonists occasionally wondering about their capacity to eat a human.

There’s also another reason that plenty of writers have been drawn to animal protagonists: the way that humans treat animals can say plenty about a person’s character. Hoke isn’t out to make grand generalizations about humans and mountain lions here; some members of each species are portrayed sympathetically, while others come off as loathsome. Hoke avoids a dichotomous position here; instead, Open Throat plainly puts its characters at the center of their own decisions — wherever those decisions may take them. It’s an unexpected note of optimism in a story that bides its time before revealing where it stands on the tragicomic spectrum.

***

Open Throat

by Henry Hoke

MCD; 176 p.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.