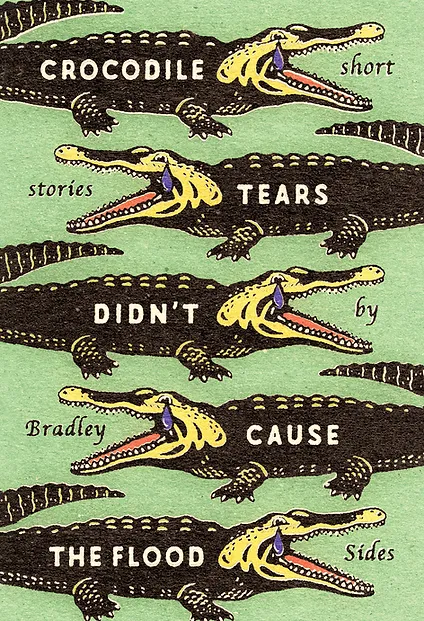

Today, we’re pleased to present an excerpt from Bradley Sides’s magnificently-titled new collection Crocodile Tears Didn’t Cause the Flood. Alexander Weinstein called the book “a traveling carnival filled with pond monsters, vampire girls, fire-breathing children, and minor apocalypses” — and that certainly has our interest piqued. Read on for a glimpse inside.

CLAIRE & HANK

(appeared originally in Necessary Fiction)

I. Before.

I can remember when I was a little kid, maybe six or seven, how all of Dad’s buddies used to make a fuss over Claire.

“Incredible.”

“Astonishing.”

“Absolutely miraculous.”

Their words.

I constantly reminded them that a Pteranodon wasn’t technically even a dinosaur, but they didn’t care. She was a giant prehistoric bird with a wingspan greater than any four of them put together. And she could fly.

It’s not like they ignored me during their visits. In fact, without fail, they’d summon me to their sides. “Hank,” they said, and they waved me over. Each time, I’d feel the smallest flutter in the pit of my stomach, thinking it was finally going to be my moment, that they were going to ask me something about the world—about myself. But when I went to them, always, they patted my head and asked if I might fetch them another ice cream sandwich or a cold glass of Kool-Aid.

All afternoon and evening, Dad and his friends took turns holding Claire’s leash, gazing at her, as she scooped down, harness-clad and all, into our pond to catch her own catfish dinner.

They had the best time watching her, too. Grown people squealing, laughing, and clapping because an ancient, human-sized bird with a toothless beak could fly and catch a few fish.

After I picked up all their sticky wrappers and crinkled cups, I sat on the bank and drew in the dirt or flicked pebbles at crickets. Anything to keep from looking up at her.

#

Dad was a paleontologist whose wife—my mother—had died during his only son’s birth. Searching for reason, for evidence, for distraction was part of him. It wasn’t so much in his blood; it was his blood.

On Christmas morning of 1981, instead of drinking hot chocolate or ripping the bow off my first bicycle, he dragged me out to excavate the far western corner of our backyard for fossils.

We were on our knees, tucked into one another to keep the cold wind from burning our faces. I held the flashlight, and Dad, with his hand shovel, dug as far into the cracked dirt as it would go, which was surprisingly far considering how it had been below freezing since the week after Thanksgiving.

Us prodding around in the dirt wasn’t a special activity. We did it just about every day. Still, Dad got excited, and he grew especially excited anytime we actually found something. He’d start screaming at the discovery of an arrowhead, the skeleton of a field mouse, or a calcified dog turd.

When he started up howling on Christmas morning, I thought Spike, the Dalmatian from next door, had probably visited earlier in the week and left us a couple of treasures.

Unlike usual, though, Dad wouldn’t stop shouting.

I was right beside him, but he hollered at me to bring the flashlight closer, and being the good son I was, I did what my father asked.

That was when I saw her, trapped in an enormous underground cave in our very own yard.

Dad wasn’t alone in his yelling then. I shook so hard I smacked the flashlight against the dirt and caused the lens to shatter.

Dad didn’t care. Truthfully, I don’t think he noticed.

In a soft voice I didn’t recognize as his, he started coaxing her out of her hole. “Come here, baby. Come on. I’ll take good care of you,” he whispered.

Claire didn’t seem scared at all as Dad reached for her. She held up her almond-colored wings, and with a couple twists and one long tug, she was back above the soil.

I almost started yelling again, but when she was eye-level with me, I was too scared to make any sounds. Just hard nose breaths I couldn’t help.

She squawked and strutted around for a bit, flapping clouds of dust and mites in

my face.

I hoped Dad would cover me with his coat, but he didn’t. Instead, he held out his hand for her to smell.

She went on up to him and rubbed her head against his calloused fingers.

That small sign of love—or maybe it was simple gratitude—was enough. He pushed me out of the way and led her inside our house like she was a newly-adopted golden retriever.

“How is she even alive?” I called breathlessly to him as he was opening the door.

“Miracle, son,” he shouted, not even looking at me. “Maybe one of those oxygen bubbles. Don’t matter how.”

Then, he slammed the door.

#

Once I was finally able to breathe normally again, I went inside. He didn’t give me any time to adjust. He told me I needed to give up my bedroom for a few nights—so Claire could have her own space to heal. A place she could make a nest and get comfortable.

Dad made me move out my few toys and clothes. I grabbed my pjs and sat on the worn plaid couch in the living room.

A terrible crash came from my bedroom. When I ran in to look, I saw Dad with a hammer and an ax, destroying my bed and dresser.

“Your sister might be able to use the wood somehow,” he said.

“My sister?”

“Yes. Claire.”

“Claire?”

“The Pteranodon.”

“The Pteranodon?”

He didn’t respond, so I walked back to the couch and sat down again, looking out at the snow beginning to fall.

He came to me a few minutes later and sat on the cushion beside me. “Be happy, Hankie. It’s Christmas morning, and you’ve got yourself a new sister.”

I rolled my shoulders.

“You should have some fun,” he said, reaching into his back pocket and retrieving a pair of scissors. “Go cut up your mattress. She’ll love nesting in those feathers.”

I took his offering. I should have stabbed her and just dealt with the consequences from Dad right then, but I didn’t. I did what he told me to do, trying the whole time to keep my tears to myself.

#

When January rolled around, Dad signed me out of school. He explained I needed to help care for Claire while he excavated the rest of the yard, looking for more Pteranodons. “Maybe we can have that big family I always dreamed of after all, Hankie,” he said.

Instead of buying me textbooks—or even boring little kid books about sharing and friendship, he said I’d be learning “life skills.” But there was a problem. The skills weren’t so much for my own life. They were all about Claire’s.

He showed me, for example, how to put on Claire’s harness so she wouldn’t fly away, which she had already tried to do at least a dozen times, and how much resistance to give her when she took flight.

After I mastered those two things, he taught me how to change her nest with newspapers each morning so she wouldn’t have to sit on her own filth, how to walk her in the yard, and how to muzzle her when she got too loud.

All of this I learned before I could tie my own shoes or make a proper peanut butter and jelly sandwich.

#

School wasn’t the only thing I had to give up because of her. My birthday presents soon went out the window. When August 17th rolled around each year, we took trips to a local park so Claire could get outside and fly around in big, open spaces on her Dad-made, duct tape and leather leash.

Dad finally got me some books to read for school after I was a couple of semesters behind, but they were all about birds, caretaking, and the prehistoric period. To make things even worse, they weren’t kid-friendly versions either. I could only figure out (maybe) ten words on each page. “A.” “The.” “Bird.” That was where I was.

I couldn’t join the soccer team or play baseball because Dad said I had to make sure Claire was taken care of.

Even my television habits had to change because the bright animation I preferred made Claire screech and shred the carpet.

I began to dream about the day I’d turn eighteen. It was going to be when I could—would—finally escape Dad and Claire.

#

On the morning of my big day, I didn’t even bother brushing my teeth. Or going to pee. Or brushing my hair. Or rubbing the sleep from my eyes.

I tore my blanket off, hopped up, slid on my shoes, and grabbed my plastic bags of clothes beside the couch—my couch—and I headed out the door.

The sun wasn’t all the way up, but I could still see Dad.

He was hunched over dead in one of his holes in the front yard. Already a mix of gray and light blue. He was forty-nine.

#

II. After.

Before I called the funeral home, I went to my old bedroom, which I’ll admit looked pretty cool with the mini-tree-house-looking space Dad had designed and painted, and I woke up Claire.

When I say I woke her up, what I mean is that I crept over to her nest and yanked one of her feathers real fast.

It’s hard to say if she could understand English or not, so after I told her Dad was dead, I led her out there to sniff him. She started squawking and flapping her wings.

I took her back inside, where she flew to the couch and squatted, and I went to the kitchen and called the number in the phone book beside the Harris and Sons Mortuary Services listing.

Some old man answered on the first ring. I told him who I was and that Dad, Hank Sr., was dead in a hole of his own making in the yard.

He said he was sorry for my loss—of course—and he’d be out soon enough, but he made me promise “the Triceratops” would be locked up.

“She will be,” I said, and I hung up the receiver.

Claire was glaring at me when I came back to the couch. Again, I’m not sure if she knew English, so I was a little scared by her look.

“Come on,” I said, grabbing her harness. “Let’s go for a walk in the yard.”

Her expression softened as I fitted it on her and we went out the door.

We walked beside the fence in silence for a couple of minutes, but that quietness was just fueling my rage. I lost it on her. Like totally lost it. I started yelling how she’d taken my dad away. How she’d taken my room away. How she’d taken my whole childhood away. I was carrying on so hard I was kind of spitting on her as I was looking down at her.

I bent down and, with my shaking, fumbling hands, undid her harness. “Go on! Leave!”

She gave me that same look she’d given me on the couch, and she started raising her wings.

With a few good pushes, she was up in the air.

“Gone on!” I yelled. “I hate you!”

She didn’t look back.

#

Claire didn’t come back for the funeral, but everybody asked about her. Dad’s buddies wanted to see her again. A couple of them had even brought her some catfish fillets wrapped in newspaper.

I told them she’d broken her harness because she was so sad about Dad and she’d left me just like he had. That hit them in the gut real good, I could tell.

They shoved the fish in my arms and said, before going to their cars, “In case she comes back.”

#

For a couple of nights, I thought about eating her fish, but each time I went to the refrigerator and unwrapped it on the counter, I covered it up again and shoved it back on the shelf. I was that way about pretty much everything. When I went in my old room, ready to take it back, I shut the door. When I grabbed a pair of scissors, with the determination of tearing a certain harness into a million pieces, I placed them back in the drawer.

I couldn’t sleep either. I laid awake, staring up at the ceiling and thinking about what I’d done to Claire. I started comparing how what I’d done to her was basically the same thing Dad had done to me.

I’d let her go.

I’d let her go, and I was all she had. All she knew. And she was helpless in the world.

I began having this recurring dream where I was walking out in the backyard at sunset, and when I looked up, there she was, flying back home. She landed right in front of me and dropped this ugly, fossilized, broken egg shell thing at my feet. I picked it up and inspected it. I can’t exactly explain why, but in my dream, I imagined it was one of her eggs from millions of years ago and she was telling me how badly she needed someone because, for her, there was no one else but me. Then, I hugged my sister, and when I wrapped my arms around her neck, it wasn’t with the thought of breaking it in half. It was to let her know I was sorry and could see we were both hurt. And together, maybe, somehow, we would be okay.

But, yeah, that was only a dream.

After I got all of Dad’s affairs settled, I thought about leaving like I’d originally planned, but I didn’t. Instead, I picked up his shovel and took to the rest of the unexplored yard, searching for something I’d never find.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.