During the Second World War, British troopers fighting in the African Theatre were issued suede boots with thick, rubber crepe soles that kept them from sinking into the desert sand. After the war, young British GIs brought their boots to dance halls and night clubs, where they became “brothel creepers.” Militaristic shoe design vanished and was replaced with woven patterns around the toe, single and double monk strap closures, and a thinner platform of about 1.5”-2.5”, usually in black or brown leather. Last year, couture fashion house Prada’s interpretation of the creeper nearly eliminated all links to not only its wartime origins, but its sartorial roots as well. Companies began manufacturing brothel creepers for mass consumption, their primary customers being the aforementioned GIs returning to civilian life, and working class youths looking to project a new public image. The coalescence produced the Teddy Boy subculture, the first of its kind in postwar England. What we wear says much about how we wish to be presented, and my research on the creeper brought me to the Teddy Boy, a pioneering subculture that linked style, music and attitude into one suit.

The first modern English subculture takes its name from a period that would have wholly ignored its principle membership of working-class youths and soldiers. The short reign of King Edward sees the emergence of extravagant fashions and a rigid class system, but also women’s suffrage and an interest in socialism. These Teddy Boys combed their hair a la Elvis and Roy Orbison, wore shoes made of rubber crepe used in desert combat, and thieved in suits that cost upwards of 20 GBP (about 370 currently). This is a subculture that helped establish a privilege of rejection, a privilege that skinheads, mods, and punks would adopt in their own worlds. While youths across the nation adopted a neo-Edwardian dress, it is this main irony that establishes the Teddy Boys as a subculture–and a very important one.

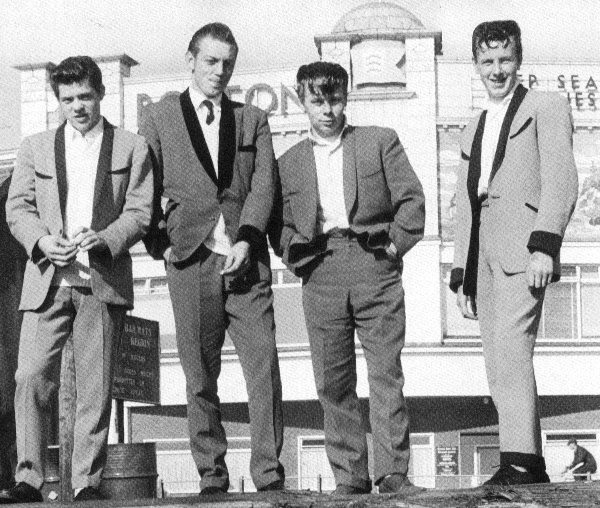

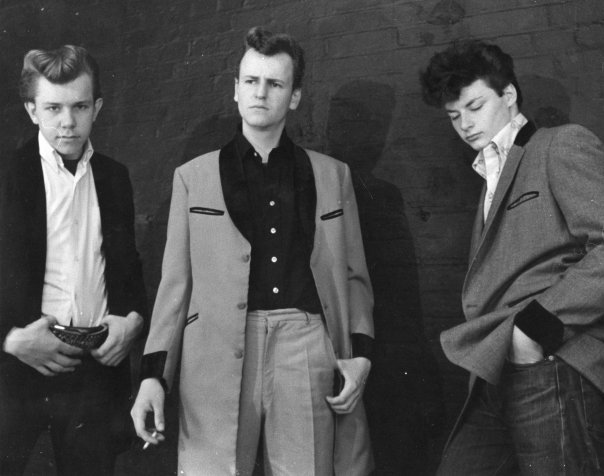

1950’s England saw increased dilapidation and depression in working-class neighborhoods, and the import of American rock n’ roll. Narratives of the post-war individual rebuilding the self are far and wide, though tales of how a style can communicate this are harder to find. The Teds’ drape coat–easily identified with their mid-thigh length, slim-straight silhouette, and velvet cuffs and collar, most recently seen by aristocrats and middle class alike on Downton Abbey–and “drainpipe trouser,” as they were called, rejected England as much as it celebrated and reestablished it. T.R. Fyvel writes in his 1963 essay, “Fashion and Revolt,” that the iconic quiff and “jelly roll” haircuts were “clearly symbols of masculinity.” “Dead-pan facial expressions” were of “special determination” amongst the working-class youth fresh from the navy ships. The teenagers growing up in war-torn England, who would proudly parade being an Edwardian–a Ted–were a new sort of Englishmen.

These working-class youths from England’s harsher neighborhoods adopted a style that brushed against their economic reality, exemplifying an attitude that set the foundation for each subsequent English subculture. The patterned brocade waistcoat and drape jackets were often made-to-order at local shops throughout England, and the footwear brands of choice were either George Cox and Robot (who still produce creepers today).This was the Teds’ way of breaking out of their exclusion from mainstream society. Fyvel’s article suggests that when Teds went broke for their outfit, they stole and burgled to keep up appearances, only further separating them from the upper classes. The mix of the hard crepe sole with the tailored trouser aimed to shake the working-class stereotype from their shirt sleeves. This only made them more exclusive, as disparaging remarks of the uniform warranted a good lashing, firmly establishing a public perception of the Teddy Boys as gang culture. The Ted was founded on the juxtaposition of hard and soft, wearing and owning what you wanted to be, but most definitely did not have.

“Ted” was a sort of side-long, cheeky glance and nod to the old culture they were rejecting. These youths were determined not to be marginalized by middle-class society any longer, no matter how they did it. Various websites dedicated to the history of Teddy Boys cite theft, beatings, and gang-on-gang violence, but the influence of American music and film are not to be discounted when discussing the stylistic and attitudinal proclivities of the Teds’. The pompadour was made popular by rock n roll in the states, and similarly imported across the pond. Cliff Richard, whom John Lennon once said was the beginning of post-war English music, performed a very American style of British rock often heard in dancehalls, wore his hair in a quiff and cradled the mic much like Elvis. Lennon’s band, too, has much to owe to American popular music. Quiff-adorned and Americana-obsessed, what kind of England were they dreaming of? More importantly, whose England? That question pervades the ideology and attitude of the Teds – if it was to be their England in the ‘50s, they would wear and do as they pleased. No one was going to tell them otherwise.

Ownership through rejection–and wearing it extravagantly–is established by the Teds, their hard-edged manners, and crisp tailoring. There was a “Teddy Boy Revival” in the 1970s, anecdotally confirmed on this site, and an apparent beef between punks and Teds over drape coats defiled by safety pins and Teddy Boy pride. It’s as if these punks, who’d had enough of England period, were now owning their England by rejecting another gang, one steeped in rejecting an England. Fast forward to 1988, and The Smiths’ final LP “Strangeways, Here We Come.” Nevermind that “The Queen is Dead” was originally titled “Margaret on the Guillotine,” but on the former LP’s opening track, “A Rush And a Push and The Land Is Ours,” our dear Morrissey croons, “A rush and a push and the land that / We stand on is ours / It has been before / So it shall be again.” The Mozzer continues to diatribe his home country, most recently about the 2012 Olympics, of which protest singer Billy Bragg showed the world this photo. Analyses of Morrissey’s irony aside, the man is quiffed, singing in front of a huge backdrop of a young English skinhead, the ‘60s most well known working-class English subcultural gang. Morrissey’s wonderful ability to mix the hard and soft, exemplified by the shirt and the young skin behind him, wouldn’t nearly be as hard if it weren’t for our young Teds, thieving some poor soul to recoup the cost of his suit.

When I look through my copy of Jim Jocoy’s We’re Desperate, or photos of old Teds on the internet, it’s easy to forget that I’m looking at something between memory and present. Kids still grow up attaching themselves to subculture, what is sometimes referred to as “youth culture,” and there are still Teds still kicking around. When does a trend, in its most sterile definition, become replaced with another? When do some become a movement? When you look at a photo of this guy [alan], or watch a video of this band, that old adage of coming and going is wont to return. The Teddy Boy, if only in look and appearance, never circled or left the block, but lurked in corners of the British cultural unconscious, helping establish what subculture is. These were the first loud British youths, the founders of “youth culture” in the east ends of London and corners of Manchester, all done in damned fine suits of velvet, polyester, and suede.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google + and our Tumblr.

2 comments