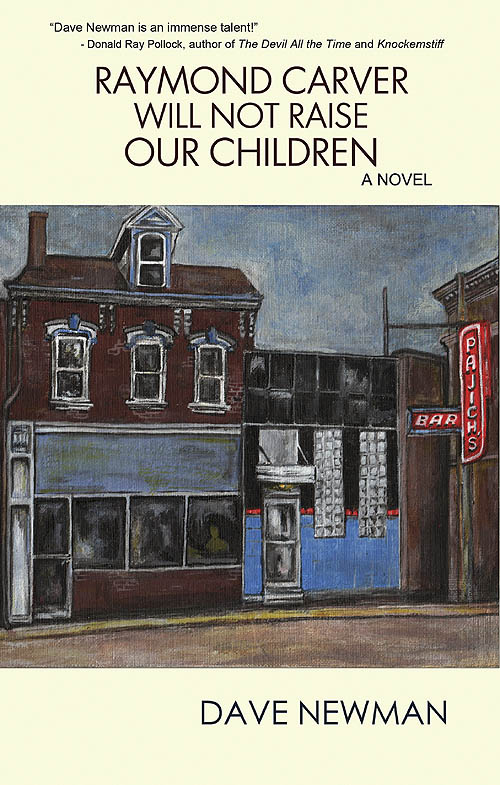

Raymond Carver Will Not Raise Our Children

by Dave Newman

Writers Tribe Books; 316 p.

Dave Newman’s second novel, Raymond Carver Will Not Raise Our Children, was released early last year, but I didn’t discover it until mid-December. I hadn’t read or even heard of his first novel, Please Don’t Shoot Anyone Tonight, but I stumbled across an article about him while Googling around about Dan Fante and Mark SaFranko. First things first: If the title doesn’t make you want to read the book, I can’t do anything for you. It’s a hell of a title and I didn’t need to know anything about the book to know I wanted to read it.

Dan Charles is the narrator. He’s an adjunct instructor at the University of Pittsburgh, begging for his contract to be renewed every year, waiting for the ax to fall. Never mind that his writing’s going well, that’s he’s put out a well-received novel. His wife, Lori, also teaches and writes and has had more success with both. Still, she’s waiting tables nights so they can pay the bills. They have two children, Abby and Townes, and a relaxed relationship that allows Dan plenty of time to drink and even occasionally to sleep with other women. When we first meet Dan, he’s in West Virginia to give a reading. The reading falls apart and he winds up bedding down his tour guide, a married woman who has read and loves his book. Dan tells us: “My rules about cheating are flexible, and they mostly revolve around not hurting my family. I try to have more rules than opportunities.” Somehow this doesn’t make us hate him.

We’re never quite sure if Lori feels the same way, if she has her own affairs, but it doesn’t matter. Maybe because Dan follows up statements like that with statements like this about the stranger he’s about to screw: “Now I want to get laid with Carla, even though I am close enough to Carla to see she is not a miracle. She is as common as the rest of us, as common as I always am, though it sounds like she has her own miracles to chase and, because she doesn’t know me, I must appear holy.” That’s the Dan we ride along with. It’s an interesting way to start the book because, for the next three hundred pages, Dan is portrayed as a loyal husband and father. If he hadn’t slept with a stranger at a Motel 6 in the novel’s prologue, we wouldn’t think he was capable of it. It’s also interesting that the novel opens away from Pittsburgh, because the book is as much about Pittsburgh as it is about anything.

Dan is surrounded by a large cast of characters: his wife and children; his best friend James, also an adjunct and struggling writer, but mostly an alcoholic with eleven years of sobriety who has just fallen spectacularly off the wagon; Richard, another adjunct and failed artist, who has been threatened by a student; Kentucky Jim, the chair of the department, an old-school Southern hardass who’s given up writing for partying; and Lila, a talented grad student, who takes up with James. We also meet others that Dan works with: the successful, tenured professors who have a line of bullshit that got them where they are and the men at the hubcap factory where he starts pulling graveyard shifts to compensate for being so horribly underpaid as a teacher. We meet bartenders and strippers and talented students and mediocre students and good-for-nothing students. It’s all a blur of cancelled classes and worried drinking sessions in local dives and Dan driving drunk down streets he could drive blind.

At one point, Lori is offered a great job at a university in Alaska. The decision to move or to stay in Pittsburgh weighs over the Charles family. Thinking that Lori might want to accept, Dan goes to Tessaro’s, his favorite joint, and gets a double order of bacon burgers and hash browns. He says, “I know there are places in Alaska to get a good burger. But the burgers in Tessaro’s are mine. I’ve eaten a dozen or more a year for two decades.” Lori visits Alaska, but you get the sense there’s no way she’ll take the job. Dan says, “If ever there was a place not to leave, it’s here.” Depending on how you read it, this could all get very frustrating. They’re offering Lori tenure right out of the gate. Why would she ever turn down such job security? Still, they decide to stay in Pittsburgh and struggle along. I don’t know many academics that would put place in front an opportunity like this. Maybe if you were leaving New York City for Panda Puss, Tennessee or Blue Fuck Falls, Oregon. Maybe then. But leaving Pittsburgh for Alaska doesn’t seem like it should be that hard. Yet it is. And that’s the heart of the book. They can’t leave Pittsburgh. They’re not your normal on-the-job-market teachers desperate for something, anything that makes them feel successful. They’re part of the city. Better to wait tables on the side and to work steamy graveyard shifts making hubcaps than to leave a city that no one loves anymore. Better to toil away in anonymity. Better to lose your house. Better to be at the bottom in a place you belong.

Nothing happens in Raymond Carver Will Not Raise Our Children, but everything happens. It’s a story of the raw life. Newman’s writing lacks artifice. It’s stripped to the bone. Not crafty. It’s the book they’ll tell you not to write. They’ll say, “Don’t make your main character a writer. Don’t make him a teacher. It’s not enough. No one wants to read it.” It’s a book that tells that advice to go fuck itself. Newman’s great influences are writers like Charles Bukowski and John Fante, writers who knew you had to be totally honest to be worth anything. After Lori has first heard back from the Alaska people and Dan is shuffling in from gorging himself at Tessaro’s, he tells us: “[Lori] is beautiful without make-up. Every year she is more gorgeous and I am more fat and worried and less handsome.” Harry Crews, who comes up in a conversation between Dan and Kentucky Jim (Dan praises Crews’s early novels and is tough on his later ones), said, “The writer’s job is to get naked. To hide nothing.” Newman’s doing that here, exposing himself to write honestly about the world, knowing that’s what matters most and shrugging off those who have a list of horseshit rules to abide by.

Above all, Newman sings beautifully of his underdog city. I’ve never been to Pittsburgh. I grew up in Brooklyn. Pittsburgh always sounded snowy. The name tasted metallic in my mouth. Pittsburgh was the Steelers and the Penguins and the Pirates, teams I either disliked or pitied. Pittsburgh was a city without a basketball team. I read Michael Chabon and poet Gerald Stern in college and Pittsburgh became something more. But never has Pittsburgh been made–for me, at least–the way it’s made here. Driving around, thinking about the possibility of leaving, Dan passes theaters and bars and schools and churches and bookstores and “the tailor who wanted a week to hem a pair of pants when I had a job interview the next day.” He knows the place inside out. He says: “I could drive like this around Pittsburgh all night, neighborhood to neighborhood.” He says: “I want something great for Pittsburgh so I write about it, knowing that my only chance for greatness is if Pittsburgh says it’s so. I don’t want to leave ever.” He thinks about Gerald Stern, gone to Jersey now, but a man who “loved Pittsburgh enough to write it down.” Later, Dan says: “So much of Pittsburgh, a city I love, has been reflected through the university I want to love but can’t because I’m under its foot or, more honestly, I hate the university and its stupidity but want to stay in Pittsburgh and I need the work and doing this kind of work, begging, makes it hard to love anything.” In the end, searching the North Side with Lori and Abby and Townes, their house lost, looking for a new place to live, Lori says, “Let’s write big beautiful novels.” Dan says: “About Pittsburgh. And poems, too.” They’ve stayed. They’ll endure. They’ll write the city down. This is how a place landscapes your heart.

Raymond Carver Will Not Raise Our Children ends with an almost-wedding and a death. Is it a comedy? A tragedy? I don’t know. It’s both. It’s neither. It’s a book born of frustration and anger and love. It’s a book about the bad joke of what it means to be a college teacher and a writer today. It’s a book about trying to live genuinely in a world that doesn’t want to let you exist that way. It’s a book about failure. Or maybe it’s a book about success. It’s a book that lets you know Ben Roethlisberger is unquestionably a jerk-off. It’s a book that dishes about great writers and bad writers and phony writers. It’s a book that lets you know what it’s like to be an adjunct, to work for shit wages and to be stomped out like something spoiled when your time is up. It’s a book about finding out what’s real. It’s a book about not selling out, about not betraying the things that have shaped you. It’s a book that’s depressing in its reality about work and money, but it’s ultimately a meditation on how to love well and truly your spouse, your children, your city, and your fucked-up friends.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google + our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.

3 comments

Thanks for the great review of this fantastic book. Cheers.

Terrific review. Terrific book. My life is richer for both. I truly believe there should be a thing called “Pittsburgh Fiction” or “Pittsburgh Novels.” If there were, this book would stand proudly among them.