I’d be surprised if this week’s events haven’t made you think about politics in at least some capacity: there’s been plenty to mull over and plenty to debate; events to inspire and events to infuriate. And so it’s not too surprising that much of my recent reading has also involved questions of political affiliation, radicalism and compromise, and issues that steadily avoid an easy resolution.

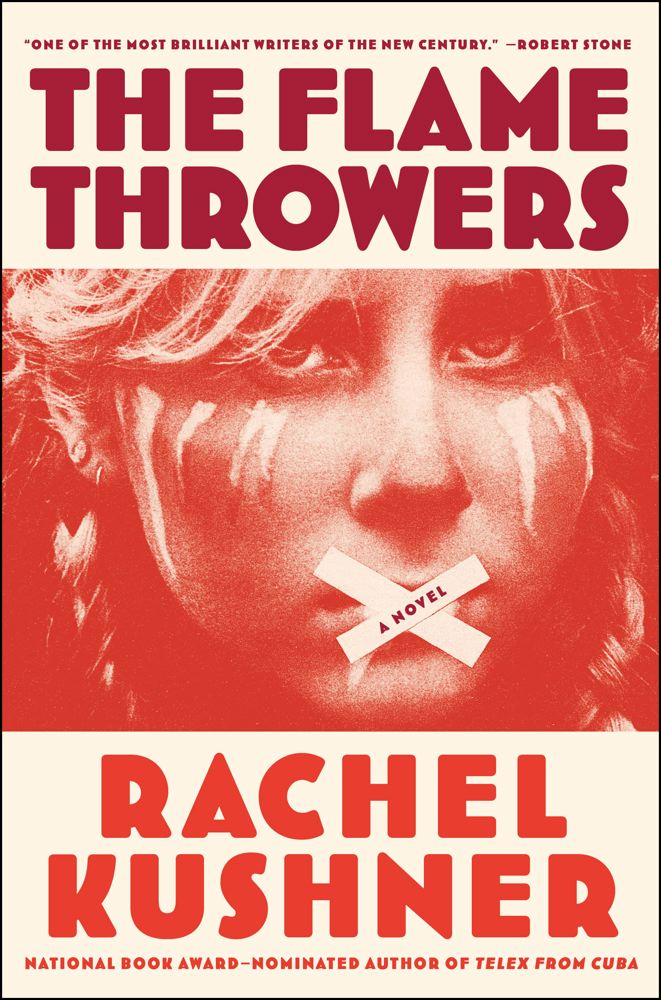

Earlier this week, I got into a relatively heated debate over the merits of Rachel Kushner’s The Flamethrowers. I think it’s safe to say that the novel has now reached the backlash to the backlash to the backlash state — probably not helped by Frederick Seidel’s less-than-impressed review of it in the New York Review of Books. For my part, I’m among those who dug the novel considerably. Is some of it that the areas in which it’s set — the New York art scene of the 1970s, the dwindling days of an aristocratic Italian family — hit a kind of sweet spot for me. But it doesn’t hurt that there’s a lot going on thematically, from a smart take on the relationship between privilege and art to a wrenching account of the ways in which ideals can corrode into fascism and exploitation. And the novel’s protagonist, a woman called Reno whose fondness for motorcycles is reflected in her work, is a memorable one — incredibly capable in some ways and stymied in others. I’d love to see this novel taught in conjunction with Melissa Holbrooke Pierson’s The Man Who Would Stop at Nothing — both accounts of motorcycles and the liberation (and danger) that they can bring.

I’m probably deviating a bit from my usual column schedule by mentioning a chapbook in here, but Mimi Thi Nguyen and Golnar Nikpour’s Punk converges pretty nicely with some of the themes of Kushner’s novels. The dialogue between its two authors discusses their own early days in punk, their more recent work in academia, and neatly dissects the notion of punk histories — and how certain areas of punk are given far more history than others. There’s more to ponder in the thirty-odd pages here than there is in works ten times its size, and if the phrase “punk is a moving target” doesn’t become something close to iconic, I’ll eat my hat. (Admittedly, I’ll need to buy a hat first, but still.)

The work in Essays of E.B. White is generally more pastoral than political, but White’s conviction on certain causes does come up in a few pieces — whether writing about bigotry, geopolitical conflict, or the dangers of pollution, he does make several impassioned cases over the course of the work collected in this volume. Some of the issues he addresses seem dated now; others remain all too relevant. Reading it at times gave me a sense of the period in which these works were written — not just the issues discussed, but the way in which they were talked about. And White’s writing about nature and life in New York remains essential.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.