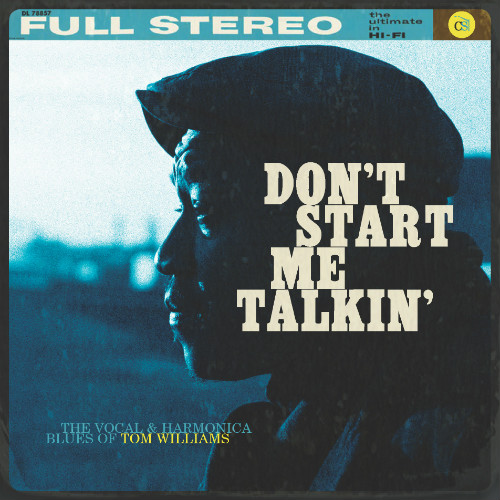

We are pleased to bring you an excerpt from Tom Williams’s new novel Don’t Start Me Talkin’, out now on Curbside Splendor. Don’t Start Me Talkin’ follows the farewell tour of Delta bluesman Brother Ben. The Chitlin’ Circuit author Preston Lauterbach called the book “a must read for fans of low down sounds everywhere,” while Matt Bell noted that “Tom Williams enters the living history of Delta Blues and emerges with his own thrilling tall tale, alive with American music, American legend, American heart.” Williams will be reading at the Franklin Park Reading Series on March 10th.

Chapter 6, “I Can’t Be Alone”

The Hospitality Committee has gone to great lengths to welcome us “masters of the Blues,” as we’re called in the letter that accompanies our security passes and programs. Along with comping our hotel rooms, they’ve invited us to take in the area’s many sights and sounds, with complimentary passes and shuttles to Tunica’s casinos, the Gibson guitar plant, some art and music museums, as well as Graceland, of all places, and a Redbirds game. Right now, Ben’s in the room, on the cell, getting directions to a health food store. Didn’t even hassle me about my present destination being Interstate Barbecue. I’m the only passenger on the elevator, and I keep my eyes closed for a minute, just to make it more exciting when I enter the lobby, hoping to see some blues legends or at least another member of the top ten harp players according to Blues Today.

When the elevator doors and my eyes open, there’s plenty of great players, of all instruments, and many styles, but they’re my age or a decade or so older. The elder generation—Cotton, Gatemouth, Koko, Pinetop and the like—must not have arrived or are up in their hotel rooms. Because Ben and I don’t play festivals, these aren’t cats I’ve jammed backstage with or sat in with on a record. But I recognize them and they me. I nod at Clay Sampson, who used to be in Luther Allison’s band, nearly bump into Mary and Buster Stewart, the “new sweethearts of the blues.” They play at least three nights a week at Tip’s, a show that’s more soul than blues, with lots of corny banter, but they’re all right. I scan the room for Blind Deacon and the Professor, though I’m not sure I’d recognize them if they stood right before me. I own one of their records, a vinyl LP, but rarely am I in a mood to hear Piedmont, and hardly ever stray from my CDs and Discman.

Larry “Bottom” Diggs, the cat from Houston who wins best bassist every year, nods at me, and I wonder if he knows me by name or is happy to see another brother. I don’t ask because he’s walking toward the revolving door, where two white kids stand, the guy with a Replacements’ t-shirt and Elvis sideburns, the girl with Betty Page bangs and black Japanese characters tattooed on her milky upper arms. “Gentleman. Ladies,” the guy shouts. “Anyone needing nourishment for the soul from Four Corners, Miss Jeri is your driver. If it’s the Mid-South’s finest Q you want, then come with me.” Doesn’t even sound like a southerner. He could be from Troy. Along with the New Sweethearts of the Blues, I find myself headed in his direction. I can put away fried chicken and pork chops, yams and black eyed peas, but my eyes tighten and my gorge rises whenever I get in smelling distance of greens, even though Ben sings in “Satisfy My Soul,” “I drink potlikker like it’s water.”

And I’m not the only one this hungry at three o’clock, as there’s a wait to get through the revolving doors and out to the two silver vans with Blues City Tours stenciled on their sides. I get my opening right after Clay Sampson and his three-piece band and step outside to wait another few seconds. I wipe my knuckles over my lips and mustache, which is thickening up nicely, though I may have spied some grays among the black hair this morning. I tug the collar of my sphinx head shirt to make sure the points lie like wings atop the collar of my jacket. Then, as Clay steps into the van and I follow, I see seated at the back Henry Taggart, smoothing his long gray-blonde hair off his patrician brow, while dressed like a hired hand in boots, bleached jeans and denim workshirt. Clay sits near him and smiles, as if acknowledging Henry’s the most famous of us mid-level acts. No one here has heard his tunes on a movie soundtrack. Most play venues where draft beer’s served in clear plastic cups, and outside of festivals and warm-up gigs. We’ve never seen more than a few grand cheering us. If the van behind crashed into this one, no one’s obituary would make it on Yahoo’s headlines, and there’d be no appearances in the memorial video montage at the Grammy’s.

The only seat left is behind the driver, so I drift toward it, first nodding toward Henry—he plays harp as good as or better than Butterfield and Musselwhite—but he’s staring forward down Union Street. The driver jumps in, welcomes us again, and has the keys in the ignition, playing it cool, until he turns to me. “Silent Sam!” he says.

My shoulders shoot back and my head wobbles side to side. Eventually, I nod and have my hand out in time for his to grab with force. “Where’s Brother Ben?” he says, as they all do.

“Up in the bed,” I say, automatically.

The driver nods, as if confirming what he already knew. “Silent Sam,” he says, starting the van. “No fucking way.”

I turn and shrug apologetically, then stop, thinking that might be too complex for Sam. As the driver pulls away, I watch from behind my sunglasses the crew of valets and bellmen working outside the hotel, most of them brothers, a few Latinos. I wouldn’t dare ask them if they liked Brother Ben and me. I’d get an answer I know too damn well.

The driver’s name is Michael Hunt. He’s heard all the jokes, which is really one joke, told over and over again, and it made a Michael out of him instead of a Mike. Two years younger than my real age, he drives this tour bus four days a week for Blues City Tours, though he’s disappointed none of his passengers ever inquires about Joe Hill Louis, the Memphis Jug Band or even Mr. Handy. “Half of them don’t even know Willie Mitchell still lives in town,” he says. He can’t drive down Beale, since it’s closed to vehicle traffic, and most of his passengers are only interested in the termination of the tour, Graceland, and the opportunity to traipse around the great man’s house.

I learn all this and more on the way to the restaurant, as Michael talks nearly non-stop. As long as I don’t have to answer questions, I’ll endure a monologue, especially one with so much praise for Ben and me. When we enter the parking lot of Interstate, Michael lets everyone know that their meals are gratis, thanks to the good people at Blues City Tours, a sponsor of the Beale Street Blues awards. Taggart, the last one out before me, smiles at Michael, and he might have said, “Sam,” as he passed. I’m not sure because Michael’s telling me that he’s in two bands, one of them a covers act that plays three nights a week at two airport hotels. “Everything from Bill Monroe to Bob Marley,” he says is their introduction line. But that gig, along with the tour bus, supplements what he’s doing with his real band, which he describes as a “blues-based quartet” called, get this, The Sons of Sonny Boy. Were I not attracted by the tangy aroma of hickory smoke and pulled pork, I’d ask him why they selected Sonny Boy. Mud and Wolf and the other B.B. make up the trio that intrigues most white boy blues players. But I don’t need to say anything to Hunt to keep him talking. As we enter the restaurant, he says, “We’re not, you know, some tribute band. We try to capture the spirit of the blues while keeping some, you know, ironic detachment and self-awareness.”

Ironic detachment? Self-awareness? That deserves a Silent Sam double take. I remove my hat, scratch my shaggy head. “Sho,” I say, then walk to a table and read the menu.

The interior of Interstate Barbecue suits me well. No gimmicks, no cute reproductions of olden days, just black and white tile floors, wobbly ceiling fans, formica tables and plenty of napkins. Requisite celebrity photos hang from the walls, though none of the waitstaff rushes to grab a camera and snap any of us from the Beale Street Blues awards. The other players sit among the customers, Clay and his bandmates in a booth underneath a photo of Willard Scott, the new sweethearts of the blues squabble at a table over who’ll sit with his or her back to the entrance, and Henry Taggart all by his lonesome in a booth at the back, the RESTROOMS sign above his regal head. My table-mate is Michael Hunt. I sit angled from him so he won’t see my contacts. He recommends I order a wet slab of ribs—I do—then asks our honey-colored waitress for the same and tells me Brother Ben and I should easily win tonight’s Best Traditional Artist. Before I fabricate humility and mumble how it’s nice just to be nominated, he asks me why Ben and I never play Memphis. “I mean,” he says. “Last year I drove down to Tuscaloosa to see you guys. My van overheated around Aberdeen on the way back.”

“I ain’t got no say,” I say. “The man tell me where to go, I go.”

“Sure,” he says, tugging his sideburns with his thumb and forefinger.

So much of what I say in Sam’s voice is a lie, but this isn’t. Never have I suggested we try gigs in other places. Why mess with the good thing we’ve got going? Why think I could tell Ben we need to play Baton Rouge or Austin in addition to our surefire towns? I suspect there’s more to Ben’s keeping us away from the Awards weekend than his alleged claims of years ago. He wouldn’t have been so hard on me about the polls if that were so. And as for why we don’t play in Memphis, Martha’s buried here, but it’s been over twenty years since she died, and I’d never say sentiment got in the way of Ben making a dollar. We also don’t play anywhere in Mississippi or Arkansas and Louisiana, these being places that don’t need to hear our honest and solemn evocations of Delta life because people like Cedell Davis and Raful Neal rip the joint with jams that sound as though they were made in the same century as the one their audience lives in. None of the brothers and sisters at Booba Barnes’s old place in Greenville is going to stand in line to see us summon the ghosts of the past, you ask me. They want to dance, not nod quietly and gently tap their feet

I tell Michael Hunt none of this. Instead, I swallow Dr. Pepper and let my eyes grow dull. Our waitress appears with a large platter on her shoulder filled with overlapping plates of ribs, pulled pork, and sandwiches dripping with slaw. One of them, I hope, is mine. I’ll be interested to see if a mouthful of rib might quiet Michael. Large oval plates in both hands, our waitress walks over. She hasn’t heard of me or Brother Ben, I bet. She might like something from Malaco Records now and then, but not a whole lot. “Enjoy y’all selves,” she says after setting down our plates. I thank her, tug a fistful of napkins from the dispenser. As I turn to my plate, though, I smile when I see Taggart eating ribs, too. With a fork and a knife.

Hunt doesn’t make the drive back to the hotel any easier, for as soon as we all get in the van, everyone smelling of smoke and heavier by two pounds, at least, he slips into the CD player Blues At Your Request, then cues it to “Take My Chance.” I don’t mind hearing us play—I’m glad I’m not the only one hearing this song—but I can’t say everyone else is as eager. However, I wish Ben were here to see our fan base might be growing. I never believed we attracted such hipsters as Michael Hunt. Few, if any, of our fans talk about “ironic distance” and “self-awareness,” when it comes to blues. “Authentic,” “genuine” and “real” are their words of choice.

On our return to the Holiday Inn, the only obvious sign of discontent with the musical selection appears when Clay Sampson’s keyboard player tosses to Michael a copy of their latest, a live recording, Let Me Hear You Holler. Judging by the title, I won’t be adding it to my collection. Clay’s from North Dakota, though he’s got good cred from having backed up Luther Allison for many years. I just hope he’s not trying to affect a showman’s routine. Out of the mouths of white boys, most patter sounds strained, especially when they put on a southern accent. Wind up sounding like Foghorn Leghorn. I say, I say, y’all feel all right?

Meantime, after every passenger but me files out of the van, “Take My Chance” comes on again. Behind my hand, I belch, savoring the smoky remnant of the ribs—perhaps the finest I’ve ever eaten—then push up from the seat, suspecting Hunt has a request. No way was all that praise and attention delivered without something in return anticipated. As my heels hit the sidewalk, I hear him say, “What are you doing tonight, Sam?”

I tilt my hat brim, run my finger over my mustache. “Gon do what the man say,” is my answer, though I only turn around part way, and mumble. Hunt lights a Lucky, blows smoke, then steps next to me. He’s not blocking my path but presses in my hand a sheet of purple paper. “The Sons are playing tonight,” he says, a little cooler than before. As if we’re not fan and idol, just a pair of working musicians. “Thought you might convince Brother Ben to come check us out.” He blows more smoke. “You too, Sam.”

I open up the folded sheet, peer at it over the top of my sunglasses. On one side of the page is a Xeroxed image of my man Sonny Boy, in his later years, dapper in a British-looking suit and derby and sidling next to a bouffant blonde. Across from that image is a group shot of Hunt’s band, mugging in a manner suggesting that each member is tough, sensitive and wise-assed all at once. The name of the club is Turner’s J.O.B., though I’m not going to ask what that stands for, as I’m sure Hunt expects I already know it. But I don’t know what else to say, other than no way would Ben spend a minute in a club. All that cigarette smoke, the harsh sound of inferior PA systems. The show’s starting time of nine would keep him out well past his bedtime. I don’t know if I want to come either. Hunt’s attention and his present request aren’t a fair measure of my fame. If Ben were here, Hunt would be all up in his business. Still, it is nice to be asked. So I face him, press my shades closer to my face, then nod and say, “We see.”

And though I start walking immediately after speaking, I don’t get far enough away to avoid hearing Hunt say, “Bring your harp, Sam. Don’t forget to bring your harp.”

I’m still too full from Interstate’s ribs and sides to attend a dinner with the rest of the nominees, and Ben just got back from the health food store. It’s now a little past eight and he’s unbagging black bean empanadas, tabouli, dried figs and a protein shake. “Found a really good deal on VISUstein,” he says, as if I have any idea what the product does. The sofa’s comfort makes me think I shouldn’t move an inch until it’s time to rack out. No need to put back on my jivey clothes, which still reek sweetly of smoke. Only I’m debating whether to go to Turner’s J.O.B., because Hunt asked me to bring my harp. He might not have even meant it, only tossed that request when my back was turned to get me to work harder at bringing Ben out. Groaning, I lean forward, push myself up and off the sofa. Ben strips the recycled wrapper from his fork and knife, settles behind his dinner at a table overlooking Third Street. “Want some?” he says, pointing at the tabouli.

I walk behind him, stretching the fabric of my t-shirt and filling my cheeks with air to show Ben how full I still feel. “You want advice? “he says. “Go with the chicken next time. Pork takes its time going down. These figs might help you chase it out. Five grams of fiber a serving.”

“That’s all right,” I say, lifting my pants off the bathroom doorknob and tugging out from the pocket the flyer for Michael Hunt’s band. When I got back from the restaurant earlier, he was asleep. I decided to put off showing him the flyer until he got back from the store. Don’t know why I feel obligated to show him now. Do I owe Michael Hunt this gesture? For all his flattery? I wait for Ben to pause in his eating, then hold the flyer before him. “Cat who drove us to the restaurant,” I say. “Wants us to come out.”

Ben dabs at his lips with a napkin, places it on his lap, then grabs the bottom left corner of the flyer with his thumb and crooked forefinger. I let it go. After a glance, he turns and looks at me the way he did those many years ago when I asked him about the judge and his first guitar. “You really thought you needed to ask me?”

“You never know,” I say, examining my pants’ cuffs.

Chewing, Ben regards me out of the corner of his eye. “You going?” he says.

In the instant I slip on my pants, I decide that I am. “Just for a little bit.”

“Hmm,” he says, cutting an empanada in two with his fork. “Bringing your Hohner?”

I stop putting on the sphinx shirt. Do I ever go anywhere without my Hohner? Still, I turn my back to Ben, button my shirt and say, “Naw. Won’t be gone but an hour or two.” I hear Ben chewing, his breath exiting his nose. I slip my jacket on, collect the white keycard from the dresser, and almost reach the door. “Be careful,” Ben says, as stern and tender as a parent. I’ve got my hand on the door handle. Still an opportunity to stay inside, call off this curious expedition. “I will,” I say, and push my way out before any more thoughts cross me up.

The show’s just likely started and Beale isn’t that long a street, but I don’t walk directly to Turner’s J.O.B. Instead, I stroll toward the river, then, at the intersection of Front, cross the street and meander east. Beale’s not quite as bad as Bourbon Street,though pedestrians spill bright colored cocktails from plastic cups, barkers holler in every other doorway, and fortunes get told by tarot-card reading mediums with henna hair and nose rings, at least there’s no simulated sex shows and transvestite strippers. A nice mix of people, too. I see more tourists beguiled by Elvis impersonators than I need, but locals are among the throng. Handsome brothers and sisters move about in sharp clothes, trying not to gawk at me in my seventies finery. They shake their heads at shabby members of our brethren, who promise white folk the best of the blues while wheezing through corroded harps or plucking the strings of guitars more raggedy than Ben’s. My first time ever on this famous street might be a real pleasure, if I didn’t feel so strange. Out here in the mid-April night, amid the squabble of people happy to spend money on overpriced menus and souvenirs and mule-drawn tours, I tighten my stomach muscles behind all my flab but can’t still the flutter deep within. Can’t keep my head clear. In my pants pockets, my fingers curl into claws. It’s the feeling I used to have when I was young and had made a decision to do something wrong, like smoke a cigarette, drink a beer or jack off. Almost expect my dick to stiffen, a development that won’t be too comfortable in these slick slacks of mine.

I’ve lied to Ben before, of course, have committed the sin of omission hundreds of times. Yet never have I done what I did tonight, tell him something I knew he knew to be untrue. Still, I want to play with Hunt’s band or at least have the option to do so, and didn’t want to explain myself. Ben would have talked me out of going, kept me on that sofa while he enumerated the virtues of his latest supplement. After I cross Beale again near Fourth, I wind up outside W.C. Handy Park near the Father of the Blues’ statue. He’s wearing a suit and holding a trumpet. If I recall correctly, he was playing marching band and orchestral dance music when he first got close to the blues. Waiting in a Mississippi train station, Handy encountered some brother playing what he later called “the weirdest music I had ever heard.” The statue depicts him as genial, courtly, respectable. If he were my employer, my mother wouldn’t mind. I start walking again, trying not to think of what she’s doing in Ghana. Most likely telling Grover she wishes somebody can talk sense into her only child. I shake my head, wipe my hand over my mustache. A temporarily empty head is what I want most of all, and I hope I find it in Turner’s J.O.B. Only way to find out is to get there. I pick up my pace.

J.O.B. stands for “Just Off Beale.” I discover this as I stand outside, waiting for the ID checker. Just below that sign hangs another, reading, “Where Historical Preservation Ends and Good Times Begin.” After a dubious glance at my Louisiana drivers license and an equally incredulous examination of my outfit—I almost flash the sphinx head—the ID checker stamps my palm and I’m inside. The doorway’s not quite a portal to my past life, but when my nostrils recoil from the stench of cheap disinfectant, spilled beer and human funk, I may as well be in one of the bars I played in East Lansing. The club-goers aren’t dressed as they were back in the early nineties—in all black or fifties’ gear. These cats look like truckers and cowboys, with big wallets and chains, sleeveless plaid shirts and straw hats, their ladies in western skirts and ornate boots. I’ve arrived between sets and don’t see Michael Hunt anywhere, though a number of people resemble him and his tour-bus partner from earlier. I count one-Mississippi, two-Mississippi before I walk to the bar to detect whether I’m the only brother here. Even the ID checker was white, and I thought you always stationed at the door massive and dark-skinned linemen whose scholarship eligibility ran out. Though it’s dark here, and I haven’t gotten a good look at the custodial crew yet, it appears I’m in a minority of one. Still, it’s time for a drink, and I order an Old Milwaukee, the closest thing to my hometown’s favorite, Stroh’s. The bartender fishes for one and hands me a tallboy, says it’s only a dollar for another hour, then points to a papier mache bust of Ike Turner and says, “In honor of the patron saint of Friday nights at the J.O.B.”

I leave two singles on the bar and open the can, hoist it high in Ike’s direction. In musical style, I feel more kindred with Tina’s old man than I do with Mr. Handy down the street, though I wonder how many people in here know anything about Ike other than what Larry Fishburne showed them in What’s Love Got to Do With It. For that matter, what do they know of Sonny Boy, the man whose quote-unquote sons appear to be mounting the stage again, greeted by shrill whistles and raised tallboys. I find my place at the rear of the club, between the Gents’ and the Ladies’, a slippery paneled wall against my back. Between me and the stage is a dance floor, ringed by tables and chairs, but there’s no room for dancing and everybody in the bar is on his or her feet as none other than Michael Hunt, in wraparound shades, a sleeveless Public Enemy shirt and tattered jeans. I dampen my mustache with another sip of beer, while Hunt grinds out his cigarette, blows smoke, then grabs the mic. Two brothers pass me by then, each weighed down by a gray tub full of empties. Now that I know that there are three of us—three and a half if you count Ike’s bust—I settle down to listen.

Back in the van this afternoon, I could have predicted the noise these fellows would make. It’s of the kind our Vegas crowd desired. The drums go boom-blat, boom-blat, the bass keeps a steady but undistinguished pulse, and the guitars chew up rhythm, until it’s time for Michael to solo. Sons of Chuck Berry or Keith Richards would be more accurate a name. Better yet, Sons of Grand Funk Railroad. Don’t hear any of the “irony” or “self-awareness” he promised in the van. Yet who am I to criticize? Played my share of this shit and now pretend, that’s right, pretend to be an embodiment of a musical tradition that’s as much mine as it is that of Michael Hunt or anybody else in his band. And hell, they at least live here, a claim one Peter Owens cannot make.

Soon time feels as jittery as their sped-up covers, and an hour passes, though it seems only half that. Over the nonstop noise of the clubgoers and through the muffled sound system, the band plays John Lee Hooker, ZZ Top and George Thorogood, and an original or two, the subjects of which are drinkin’ wine and steppin’ out. What enlivens the people here most, though, is the patter Hunt manufactures between songs. No surprise after this afternoon to find he’s an onstage talker, only now his voice doesn’t sound as suburban. Everything he says is nipped from Joe Tex and Peter Wolf, yet it takes on a ragged and Dixie-fried edge that sounds legit when he exhorts the crowd to Get nekkid or asks Y’all feel awright.

Now he’s rapping about the blues and how people in Memphis are lucky to live in a town where so much good music was made. Behind him, the rest of the Sons play a quiet shuffle, keeping it slow and rumbling like a distant storm. I’ve finished my Old Mil and don’t need another. I tune in closer to what Hunt’s saying. “I know y’all been to Memphis in May. I know y’all been to Sun Studios. Some of y’all been to Graceland.” The crowd boos but quiets once Hunt waves both hands, then yanks off his shades. He assumes a stance and grip on the mic like those of the Marines at Iwo Jima. “But how many of y’all know about the Beale Street Blues awards tomorrow? How many of y’all know the best, I mean, the best of the blues is in town and probably just for another day?” The response from the crowd is mixed, people not knowing if they’re being shamed or prodded to act. Meantime, the rest of the Sons of Sonny Boy have picked up the pace with their shuffle, and Hunt falls to his knees. “But we extra lucky tonight, good people,” he says. “All y’all visitors to the Friday night throwdown at Mr. Turner’s J.O.B.” He stands up now, his limbs loose as he points to the bar and salutes. “First a toast to our patron saint of Friday night, Mr. Izear ‘Ike’ Turner, the founder of rock and roll long before he was kicking Tina’s ass.”

A lusty shout of approval emerges, nearly from every voice in the club except mine. Might be time to leave, as I can’t quite tell if Hunt’s delivery amuses or pisses me off. He’s swerved into the quasi-black dialect that manages to parody more than praise. I look for a trash can to toss away my empty—don’t want to make the two man clean-up crew work any harder than they have to—when Hunt says, “But tonight, like I said, good people, we extra lucky. Why? Cuz, y’all, we got—“ He quiets, raises one hand, drops it the same time as the drummer hits his crash cymbal—“we got somebody here tonight. Somebody who’s been there. A man from the Delta, where the blues was born. All the way from Natchez, Mississippi, good people, Mr. Silent Sam Stamps!”

How did he know? I know I’m somewhat easy to find, but not amidst all this dim lighting and cigarette haze. Did he know I was coming when he invited me? Somebody tip him off? The bartender? A spy out on Beale? Ben? Whatever the case, I don’t want to embarrass the man, and so far the only request appears to involve me walking to the stage, which I do, tripping over no one, the crowd parting to give room, though no one applauds the way they would had Hunt said, Mr. Al Green or Mr. Buddy Guy. I reach up for my hat brim, touch nothing but the stubble of my recently trimmed head. What’s that a sign of? Bad luck if you leave a hat on the bed, what about when you forget it as part of your disguise? When I reach the stage, I see the bassist, who also approximated back up harmony for Hunt’s lead vocals, has moved center stage, freeing up a mic. I wave to the crowd, rub my hands together. “Mr. Sam Stamps,” Hunt says again, and the applause sounds like rain that might shift from a drizzle to a downpour.

Meantime, the rest of the band steadies their rhythm, with Hunt joining in. No single tune has emerged, just a passable shuffle, easily sped up for Chicago, slowed down for Delta. Hunt’s eyes widen and he shrugs, a gesture any musician knows means, What do you wanna play? I haven’t even taken my Hohner out of my pocket. Haven’t made a motion or said a word. Do need some practice, though, which is what I’d be doing if I were back in the room with Ben. Thinking of him while I shake my harp and bring it close to my lips, I recall one of his tricks. I’ll give the Sons of Sonny Boy a tough number, and if they can’t find their way in, I’ll wave and duck back into the anonymity of Beale. “ ‘I Can’t Be Alone,’” I say to Hunt, just barely knowing the lyrics. I quietly play the intro, then Hunt shouts: “Ain’t no way in the world, I can be by myself.” Nothing left to do then but close my eyes and blow.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.