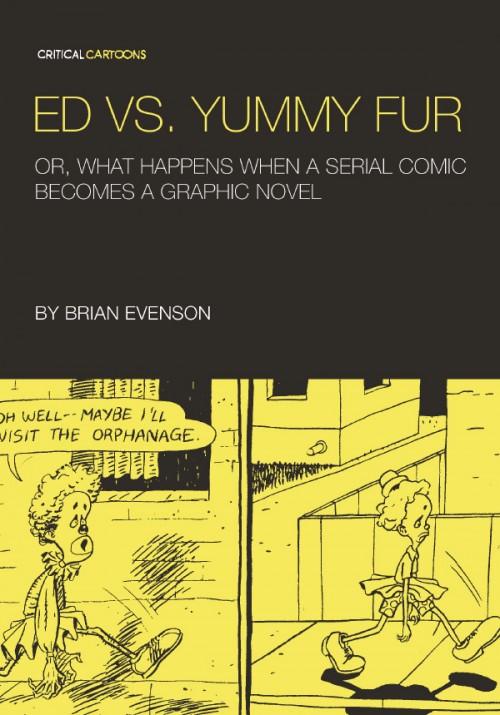

Ed vs. Yummy Fur

by Brian Evenson

Uncivilized Books; p.

My birthday gift to myself two years ago was Chester Brown’s Ed the Happy Clown–a comic I first heard mention of in my late teens, thumbing through (if memory serves) old issues of Film Threat. A few years ago, I read Douglas Wolk’s Reading Comics, a large portion of which is dedicated to profiles of significant modern creators. Chester Brown is one of them, and the then-out-of-print Ed piqued my interest. I remember taking a long walk down a bar, the comic in my bag; I remember reading it the following day, and I remember being put into a state so disjointed that “unnerved” doesn’t really do it justice.

Uncivilized Books, who have mainly been on my radar due to their work with the always-fantastic Gabrielle Bell, have launched a series of short books, the Critical Cartoons series, in which an author engages with a particular work. The first of these involves Brian Evenson writing about Brown’s book–so, one writer for whom religion and violence are pet themes engaging with another work where religion and violence are central.

Ed the Happy Clown begins with a series of short vignettes; slowly, a plot coheres, involving the title character, a parallel universe beset by an overabundance of shit, an artist who turns murderous, religions visions, vampires, and a werewolf-obsessed scientist. Attempting to describe the events of the book might make me sound insane–or might suggest that I’m trying to describe a plot where there isn’t one. Speaking as someone who’d first read Ed in its latest incarnation, though, the plot comes together fairly neatly. But for me, that may be because I read it the current edition. Those who first encountered Brown’s comic Yummy Fur (and both Evenson and Wolk fall into this category) will likely experience this differently.

One of Evenson’s big themes here is the question of context. In Yummy Fur, Ed the Happy Clown was paired with Brown’s retelling of the Gospels–which, in turn, made for an interesting contrast with the riffs on sin and damnation in Ed. There’s also the question of the way that Ed was constructed: some single-page comics have become part of the larger narrative, while others have not. And certain plotlines have been revised over the years: fates made more clear, subplots jettisoned. The book closes with a long interview of Brown in which he discusses his narrative choices, with Evenson pressing him on certain decisions.

It’s one incarnation of a perpetual debate about narrative, and about versions: can a definitive version of something be said to exist, especially now? As long as multiple versions of works from Smile to Star Wars to Raymond Carver’s short stories have existed, debates have raged about authorial intent and personal preference. Evenson’s book is, among its many other qualities, an extended meditation on these issues. It’s also another window into a creative work that’s frustrating, vulgar, and–for me, anyway–utterly captivating.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.