“Cults, you know? Why is it people have such a fascination with them?” The question—posed in Peter Stenson’s new novel, Thirty-Seven—is timely. Of late, culture itself seems to have become a sort of cult of cults. Emma Cline’s 2016 Manson-inspired novel The Girls received more press (and a larger advance) than any one book could arguably merit. More recently, there’s the endless parade of news items about the impending Manson film by Quentin Tarantino. It hasn’t even started shooting, but barely a day passes without a fresh rumor emerging. And what can one say of our national Scientology obsession, except that seems both ridiculous and utterly justified? I’m certainly not immune to the craze. Whether reading Cults in our Midst or watching the documentary Holy Hell, I could hardly be more rapt than I am by the unaccountable passions of such oddball devotees.

The above-quoted character in Thirty-Seven speculates about our collective enthrallment. “It’s kind of like how when people say that the real fear of standing on a cliff isn’t that you’ll fall, but that you’ll jump…People are obsessed with cults because it’s so easy to see yourself falling into one.”

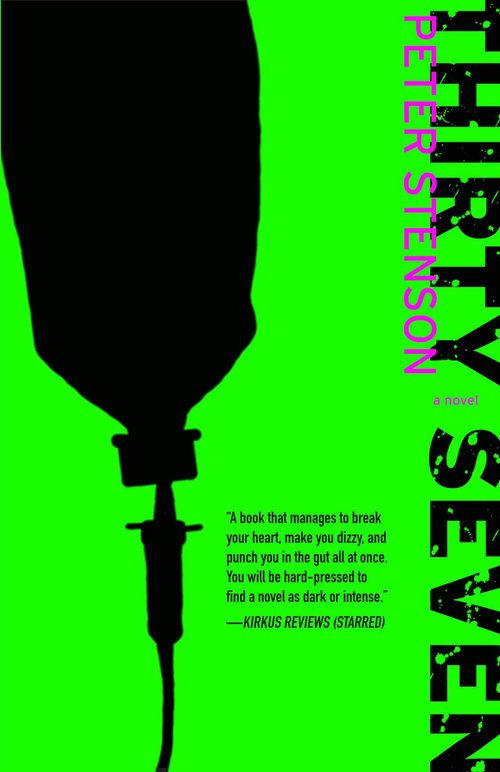

Perhaps. Though I’m hard-pressed to imagine myself falling into the cult described in Thirty-Seven, in which the members, known as Survivors, voluntarily endure megadoses of chemotherapy and the inevitable racking illness that follows. The meds are administered by their leader named One—a.k.a. Dr. James Shepard—a former oncologist who lost his daughter to cancer and, well, one thing led to another.

The narrator was called Thirty-Seven in the cult, but he’s been known by a variety of names. Mason Hues is the name given by his adoptive parents. Then there’s John Doe, the name used by the authorities that dealt with Hues in the months and years after the cult’s violent reckoning. The story unfolds in parallel timelines—the present in which Mason lives in Denver having recently turned eighteen and been released from incarceration, and the past, in which, as a fifteen-year-old, he runs away from his parents’ home in Boulder and makes his way to the mountainside retreat in Marble, Colorado where the cult lives.

Well, “retreat” might be overstating it. The place sounds beautiful, but the bedrooms are filled with bunk beds (a cult staple since Heaven’s Gate took to the skies) populated by bald, bone-thin members of the group, each of them in some stage of sickness—vomiting, shivering, diarrhea, fatigue—brought on by intravenous infusions of the drug Cytoxan.

As he recalls his days with the group and the escalation of their activities, Mason also describes his new life in Boulder, where, in exchange for his testimony, he receives “food stamps, medical insurance, and covered rent for two years of Section 8 housing.” He takes a job working at a thrift store named Talley’s Tatters, where Talley, his boss, becomes his only friend, introducing him to some semblance of Boulder nightlife—her boyfriend is in a band—and attempts to teach him how to behave more like a human being and less like a robot spouting the fortune cookie insights learned from the group.

When not with Talley, Mason stays in his sparsely furnished apartment, watching Netflix and obsessing over a true crime book about the cult called Dr. Sick: The Survivors and The Day of Gifts. Peter Stenson does a particularly effective job of evoking this document, which is described and quoted from at length throughout. At times, I wished I could read it myself as a supplement to Thirty-Seven.

Things get complicated when Talley, who has also read Dr. Sick, discovers Mason’s true identity—not an orphan trying to make his way, but a runaway and famed former cult member whose identity was never released to the public because of his status as a juvenile. Fascinated by his past, she persuades him to start the group again, this time with the uncorrupted intentions that its original leader couldn’t maintain. He will be the new One, and she his Two. Soon, they’re on daily does of ipecac and laxatives, replicating to the best of their abilities the Survivors’ trials.

As their story careens to a crescendo, so too builds the story of Mason’s time as Thirty-Seven, as his group transitioned inevitably from violence inflicted upon themselves to violence inflicted upon others.

Undeniably compelling and well-written, Thirty-Seven left me with the smell of bile in my nose and a few questions about the true nature of its not-altogether-lovable protagonist. The trajectories of cults are almost as rigid as that of romance novels—from wide-eyed idealism to blood drenched hands. In that sense, Stenson hits all the expected beats. But within the prescribed structure, he manages to generate a genuine sense of surprise. A third-act question of identity is as engrossing and unexpected as anything Helter Skelter has to offer while erasing all doubts about Mason’s motivations.

The book’s greatest weakness comes in the form of an off-putting quality to some of the language. I winced my way though a few sections meant to conjure the pseudo-deep philosophy of the protagonist and his former leader. “Consciousness is a disconnect from God. We are God. Consciousness is a disconnect from ourselves.” One two-page passage meant to take the air out of the American Dream overstayed its welcome by about a page and a half. However forgivable these lapses into cult-think might be, given that the narrator is an incredibly screwed-up eighteen-year-old, they do grow tedious.

If you ask me, the reason we’re obsessed with cults is that they lay bare our human need to belong, to find pure acceptance and connection so powerful that we might be inspired to suspend our disbelief and go all-in. Which, I suppose, is something like Talley’s suggestion that we might find ourselves leaping off the cliff instead of peering over its edge. In its depiction of this notion, Thirty-Seven is an unmitigated success, evoking our mundane need to belong while reveling in the irresistibly lurid details we all yearn to know about the lengths—including sex, drugs, and murder—to which some seekers travel in order to feel loved.

***

Thirty-Seven

by Peter Stenson

Dzanc Books; 216 p.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.