Sometimes horror stories play out like puzzles to be solved. That’s not too much of a surprise: plenty of writers have done acclaimed work that falls under the header of both “mystery” and “horror,” after all, from Edgar Allan Poe to Stephen King to Elizabeth Hand. And in these sorts of stories, there’s a sense that the overarching terror might be abated if only a solution is found to something: an ancient crime unearthed, an old price finally paid. But there’s another subdivision of horror that hears a different call: specifically, that horrific events play out under their own logic, and no easy answer can be found for them.

This emerges frequently in the fiction of Robert Aickman, Rachel Ingalls, and Kelly Link: bizarre things happen with no easy answer, where comprehensive understanding is wholly impossible. It isn’t quite the same thing as cosmic horror — there are no otherworldly entities, and no overpowering sense of terrestrial doom — but it taps into some of the same anxieties. In these stories, resolution may well beyond the powers of human understanding — but the danger is no less real.

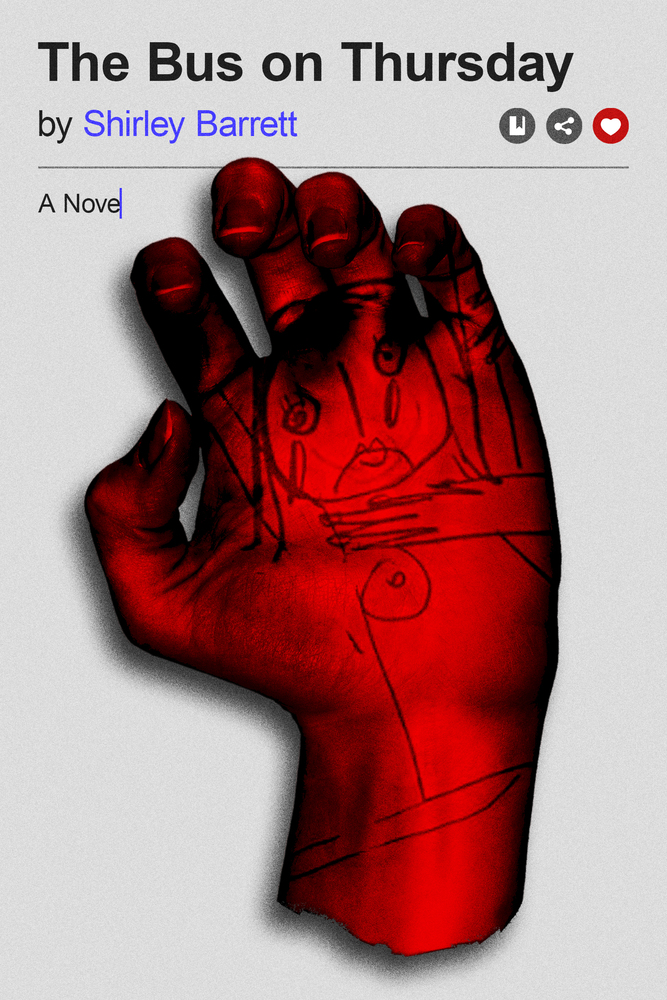

Shirley Barrett’s novel The Bus on Thursday falls decidedly into this camp: stylistically, it reads like a blend of Kelly Link’s ominous surrealism and the strange absurdism of Magnus Mills (whose fiction has no shortage of sinister moments itself). It opens in the aftermath of narrator Eleanor grappling with a very real horror: a breast cancer diagnosis, and a series of physical and emotional upheavals to follow–which leaves her unemployed, with few prospects for more work. After a long period of frustration, she leaves her home for a job teaching in a rural town named Talbingo. And it’s there that things take a turn for a much different version of the horrific.

Eleanor’s predecessor at the school, it transpires, has vanished under mysterious circumstances. Talbingo’s isolation isn’t confined to its location: cellular signals and internet connections are also spotty there. And then there’s the local priest, who argues that Eleanor’s cancer was caused by a demon, and who offers to exorcise it. This is a scene that’s unnerving for both the priest’s matter-of-fact demeanor and for the way that this decidedly irrational take on the supernatural is the most rational harbinger of the weird to show up in the novel.

Much of the power of The Bus on Thursday emerges from Eleanor’s increasingly unsettled sense of place. Without going into too many specifics, identities begin to grow blurry, odd visions recur, and the case of Eleanor’s predecessor at the school begins to take on an increased significance. There’s a sense of porousness here: the line between life and death seems traversable, but so does that of the real and unreal. Eleanor’s method of narrating the book — a series of blog entries — would seem to be pristine in its documentary qualities, but even that proves to be less than reliable over the course of the narrative.

Eleanor’s voice, too, remains memorable throughout: her frustrations and desires are eminently relatable, and her flaws make her story that much more unsettling. On one level, this is a story of an ordinary person dealing with the extraordinary — but even the most clearheaded investigator of the unknown might be stymied by the mysteries of Talbingo. Barrett’s novel abounds with a steadily advancing dread, even as it’s tempered by bursts of bleak humor. The result is a subtly unnerving novel with a sinister climax, and some imagery that’s hard to forget.

***

The Bus on Thursday

by Shirley Barrett

MCD/FSG Originals; 290 p.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.