I really ought to dislike duncan b. barlow’s writing. He writes in tiny punchy sentences, and to make them, he sometimes divides complete sentences into ungrammatical clauses. I am a Proustian all the way, insisting as I do on long winding sentences with many joined clauses, using commas to get my way, breathing only when necessary. (See?) But goddamn if I don’t love barlow’s writing anyway. Goddamn if he hasn’t done it again, whatever incredible thing he does as a writer, with his new novel, A Dog Between Us. It’s an intense piece of work, revolving as it does around two people in the narrator’s life who are dying in different ways. Its shape and symmetry remain elusive, and its plotlines taper instead of ending. But the reading experience is akin to—if you’ve never done this, I pity you—sitting on a plastic sled attached to the back of a moving vehicle. Joy and danger mixed together, roped to an unfailing engine dragging you along.

The narrator of A Dog Between Us, Crag, returns to Kentucky from his home in Seattle to nurse his father, whose health has taken a turn for the worse. In so doing, Crag reunites with Emma, a woman still in Kentucky with whom he has a complicated history of attraction and friendship. He and Emma fall into a heady, closed love, establishing the rhythms of a committed relationship too rapidly to sustain. Over time, Emma proves jealous and unstable, and meanwhile, Crag’s father goes through ups and downs of health and sickness that cause Crag enormous grief and his own measure of instability. The chapters, in the first two sections of the book, alternate between Crag at the hospital and Crag with Emma in a disorienting, non-chronological timeline. His father’s condition improves such that he goes back to Seattle, but then declines such that he returns to Kentucky, and when these concrete events happen in terms of the progressing relationship with Emma is not clear. His father’s death has happened in the first few pages’ narration, but it actually happens somewhere around page 140.

Grief tends to muddy the mind. The subject of the book makes its fuzzy chronology appropriate, and the power of barlow’s language, as well as the immediacy of his emotional textures, render the confusing qualities of A Dog Between Us irrelevant. The chapters about Crag’s father in the hospital are a howl, a screed of pain, a detailed testament to the hell of dying in the American healthcare system. The schedule, the food, the sheer invasiveness of medical intervention, the seesaw of improvement and decline—it’s all there, recognizable and horrible. “This is what it is to care, I told myself…We eat candy bars from vending machines for dinner and drink cola. We lose track of days and nights and sleep upright. We learn to ignore the clamor of machines and read books in the near-dark.”

Because Crag’s account of his father’s illness and death is so vivid and wracking, the chapters regarding Emma have a little less oomph. Emma is a compelling character, although what’s quite going on with her mentally isn’t clear. barlow drops red flags carefully, gradually, never making her seem outright dangerous. “Memory is not a linear narrative, I had said once. Fuck you, it is, she had argued. It had better be when I ask you to be honest.” Finally, Emma commits a violent act involving her dog, the particulars of which never come into focus. The book could have illustrated Emma and her struggles more fully, but barlow made the right choice in investing Crag’s father with the most emotional resonance.

As for the dogs: Emma’s dog and Crag’s dog wander in and out of frame repeatedly, holding significance as creatures of unconditional love. (Emma’s love is conditional, and Crag’s father’s love has vanished.) Bereft after Emma’s breakdown, Crag takes his dog to Mexico. He does the disaffected expat thing for a while, until he becomes entangled in death again, in the form of a sick child and his grandmother. The narrative leaves off there, with Crag trying to succeed with the child where he failed with his father (and potentially with Emma). The book’s final section is less a conclusion than it is a messy meditation on failure, but again, barlow has made strong choices as a writer, if not as a plotter. There is no tidy end to grief, no moment where a living boy can replace a dead man and bring peace to the grieving. There’s just wellness or illness, improvement or decline, and if you’re lucky, a dog to provide succor in the moment.

This summary does not adequately represent the intensity of A Dog Between Us, the sheer stunning experience of reading barlow’s sentences for 250 pages. He compresses complex emotions into tiny, devious clauses: “I show my teeth in some way that’s meant to be a smile and say, I have my own issues.” Nor have I explained the philosophical underpinnings of the book, the subtext that tangles within it the act of bearing witness to death, the triangulation of emotion between people, and the consistent metaphor of language. “I arrange words in sequences. Think of how I’ll write about this. One day. I have always written about death. About sadness. Yet, when I’m in the mouth of it, I’m devoid of language. How many days did I sit there in silence, staring at my father?

barlow’s little sentences should sound halting, stilted, in the reader’s mind, but instead they form a hypnotic rhythm, clicking and tapping like echolocation. Feeling their way toward the heart, where they bite down and don’t let go. As a stylist, barlow is one of the best-kept secrets in American indie literature, and A Dog Between Us proves that better than any of his work to date.

***

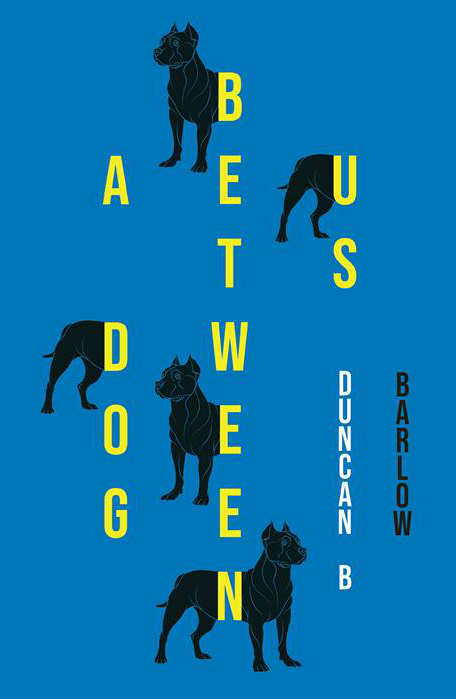

A Dog Between Us

by duncan b. barlow

Stalking Horse Press; 248 p.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.