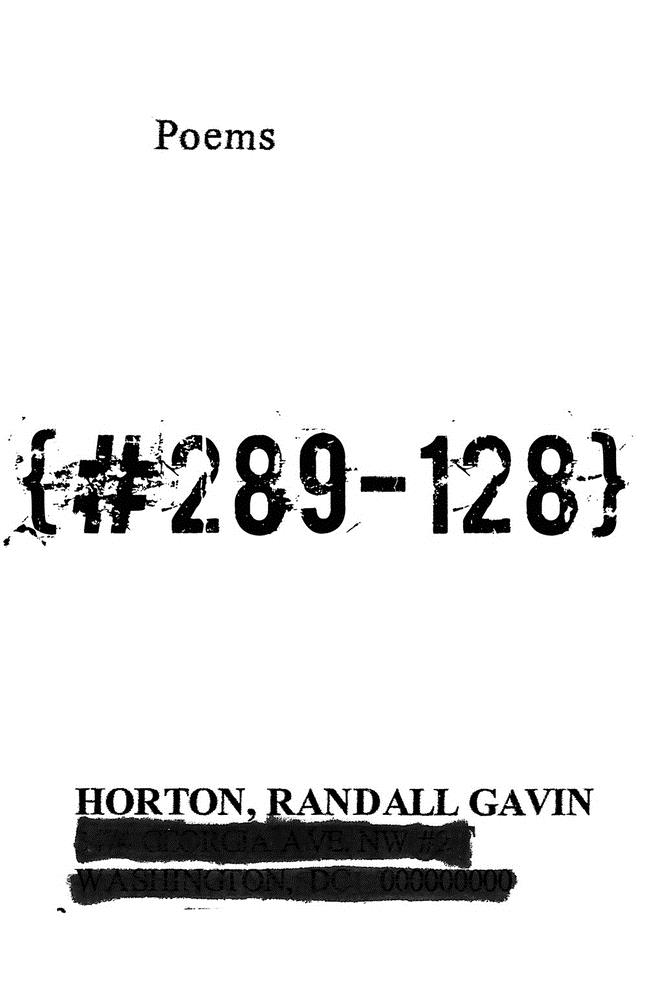

Though I’m not typically one to write reviews for works of poetry, I was happy to take on {#289-128} by Randall Gavin Horton — a collection of poems that examines mass incarceration in the United States.

Though I’m not typically one to write reviews for works of poetry, I was happy to take on {#289-128} by Randall Gavin Horton — a collection of poems that examines mass incarceration in the United States.

Horton divides his book into three sections: Property of the State, Poet-in Residence, and Poet New York. Each section follows the trajectory of the speaker ([#289-128]) from when he is turned over to the state to when he manages to reclaim his identity after his time is served, illustrating the ways in which a prisoner remains imprisoned beyond their time on the inside.

This is a compelling and teachable collection, a book that speaks truth in a time when corporations and politicians scheme to profit from the imprisonment of people of color. The mostly narrative poems give a small glimpse in the speaker’s life, each forming a larger picture which argues that imprisonment is not isolated to incarceration, but that it extends beyond prison and controls the prisoner’s life long after he serves his time through social stigmas and criminal background checks. Moreover, it examines the way in which the prisoner struggles against the long-lasting mental damage incarceration causes.

At a language level, Horton works to subvert or challenge the authoritarian language of incarceration. In the poem “Counterproductive Definitions Within The Criminal Justice System,” a poem that spreads across two facing pages, where Horton explores the relationship between incarcertus and prisonier, the mythical phoenix, the stain of incarceration, and Jim Crow, we are invited to read the poem in two ways, downward or from page to page, left to right. The notion seems to indicate that we can come to these terms in more than one way and that we are all subject to their imprisonment. Horton Writes, “trapped within a carceral state a bird—/a person or a thing but mostly a thing/,” but he also writes, “trapped within a carceral state a bird—unable to resurrect from burnt ashes—”.

In “Ars Poetica (3) Art As Poetica,” a poem occurring in the final section of the book, the speaker comes to some conclusions, and in a somewhat narrative poem, lays them out clearly, “forget about revisionist history or the body./ say xenophobia, but say it backwards, now/plainly, to the holy ignant this be not a test/ extract ignant from the alphabet take back/the illegal naming of things/ trying to love pilgrims pulled up buy a helping hand:/take back murderers who invented whiteness./ i am not post or post-racial or post-human. i am/color-constructed [#289-128] & you can’t take it back.”

Here, the play with saying and reading asks us to reconsider the power in language, to force us to think about each word presented in the poem and question our relationship to it. But it also requires us to think about the framing of race in the US, and the inescapable history of whiteness and Blackness and violence that created this nation.

What Horton ends up with is a book that is deeply empathy-inducing through stylish poems that are effective, heartbreaking, and haunting. A humanistic endeavor that creates a kind of dialogism between the poet and readers, it’s a collection worth considering for your reading lists.

***

{#289-128}: Poems

by Randall Gavin Horton

University Press of Kentucky; 104 p.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.