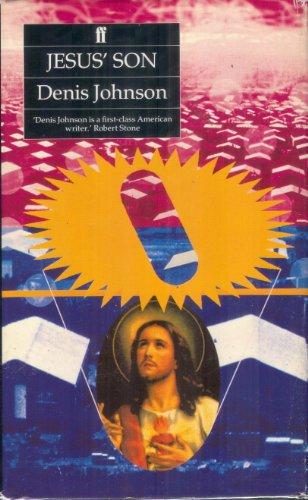

It’s been three decades since a slim volume of 11 interconnected stories, cobbled together for a few thousand dollars to keep the IRS at bay, changed the landscape of American literature. Denis Johnson’s Jesus’ Son is one of those books you read in a single sitting, again and again. It’s a repeat offender, in the best sense of the term. A professor at Brooklyn College handed me my first copy in the late 1990’s—he said only this: “Read this. I’ll say no more.” I read it often, and I’ve been handing it to students, friends, and family members ever since. As we reach its pearl anniversary, I can’t help but connect this book with Matthew 7:6 and not “casting your pearls before pigs, lest they trample them underfoot, and turn again and rend you.” Such is the wisdom of this small, epiphanic book about a drifter, druggie, drunk, and ne’er do well as he slowly finds himself working out of drug addiction and acedia and toward a hard-earned, sober redemption and reengagement with the world.

Here in Jesus’ Son, we roll across a charred and broken American landscape of lost souls and fragmented American dreams—places like Missouri, Iowa, Washington, Arizona—from car crashes, hustles, and work stints to day-drinking in hole-in-the-wall dive bars with Fuckhead, our drug addicted, hopelessly lost narrator and tour guide. In many ways, Jesus’ Son reads like a 12-step journey to God and sobriety. And, it is that and much more. By the end, when we reach “Beverly Home,” our narrator has found employment in a nursing home and started on the road to recovery. He’s writing the community newsletter at Beverly Home and working with patients, even as he plays peeping Tom on a Mennonite couple, listening mesmerized to the wife singing in the shower or waiting to catch a glimpse of the couple making love. Sure, this part of the final story is creepy, but he admits as such: “How could I do it, how could a person go that low? And I understand your question, to which I apply, Are you kidding? That’s nothing. I’d been much lower than that. And I expected to see myself do worse.” And ostensibly he’s right. The whole scene alludes to the Old Testament, when David watches Bathsheba from his rooftop, and then calls the married woman to his palace to have sex with her. Then, David sends her husband Uriah to the front lines of battle to be killed, after he’s learned that he’s impregnated Uriah’s wife. Yeah, it could definitely be worse. And that’s the point. Johnson’s stories don’t point to a lightning-strike, pure redemption, but rather, to a very real one of increments, steps, and hard work. The victory is the acknowledgement of his commonality with other addicts and lost travelers. The haunting last lines need to be heard: “All these weirdos, and me getting a little better every day right in the midst of them. I had never known, never even imagined for a heartbeat, that there might be a place for people like us.” It’s a beautiful sentiment—not a hallelujah from the mountaintop, but a man quietly setting his path straight, slowly, by doing his daily work. Johnson sets this last story in Phoenix, so the narrator rises out of the ashes of his own burning. It’s beautiful and biblical. We don’t get the Messiah rising on the third day, but we do see someone with a newfound zest for living and being a part of common, everyday life, and that’s enough.

Sentences grab a hold of you in Jesus’ Son, and pull you into their paradoxical beauty, in the midst of despair, disillusion, and ugliness. In reading it this time, I saw it a hero’s journey. In the opening story “Car Crash While Hitchhiking,” probably the most powerful story for me, the narrator tells us the following:

At the head of the entrance ramp I waited without hope of a ride. What was the point, even, of rolling up my sleeping bag when I was too wet to be let into anybody’s car? I draped it around me like a cape. The downpour raked the asphalt and gurgled in the ruts. My thoughts zoomed pitifully. The travelling salesman had fed me pills that made the linings of my veins feel scraped out. My jaw ached. I knew every raindrop by its name. I sensed everything before it happened. I knew a certain Oldsmobile would stop for me even before it slowed, and by the sweet voices of the family inside it I knew we’d have an accident in the storm.

I didn’t care. They said they’d take me all the way.

The pitiful hero with a wet cape, racing thoughts, and suicidal ideation waits on the highway to be taken all the way. That singular sentence, repeated every time someone mentions this book, I knew every raindrop by its name, provides that spark of magic, for what it is otherwise a sad case of a drugged-out drifter alone on a highway, waiting for a lift in a rainstorm. During the story, the crash occurs and the narrator watches. He really is incapable of much else, and that’s what sets off his hero’s journey. He is holding a child and he doesn’t know who is alive or dead anymore. The question is: Is he alive or dead? His journey leads him down into despair and darkness, only to return in the final few stories to light and hope in the world through connections with other people. The final paragraph of “Car Crash” in the hospital is worth noting.

It was raining. Gigantic ferns leaned over us. The forest drifted down a hill. I could hear a creek rushing down among the rocks. And you, you ridiculous people, you expect me to help you.

The bookend stories from the beginning to end move the narrator to helping those “ridiculous people”—and instead of watching a family waiting for help in the dark in the opening story, he gets on a bus, goes to work, and continues his road to reengagement with life and recovery in the final one. It’s a full circle journey from darkness into light, from despair into hope, with several key threshold moments in between.

Each section in Jesus’ Son has moments of haunting transcendence, as the narrator grapples to find his way through the dark. In “Two Men” he and his companions try to lose a mute football player they’ve picked up, eventually ditching him into a rotted stop sign at a crossroads. The reader is left thinking about ghosts and haunted shells of the self. A few pages earlier, the narrator notes this about a dilapidated house they enter: “The house looked abandoned, no curtains, no rugs. All over the floor were shiny things I thought might be spent flashbulbs or empty bullet casings. But it was dark and nothing was clear. I peered around until my eyes were tired and I thought I could make out designs all over the floor like the chalk outlines of victims or markings for strange rituals.” It’s moments like these that haunt me—moments of perception, which could signal the broken flashbulb dreams of escapism, or perhaps the evidence left after a crime.

In “Out on Bail” we meet Jack Hotel and the infamous Vine bar, which we revisit throughout the collection: “It was a long, narrow place, like a train car that wasn’t going anywhere. The people all seemed to have escaped from somewhere—I saw plastic hospital name bracelets on several wrists. They were trying to pay for their drinks with counterfeit money they’d made themselves, in Xerox machines…The Vine was different every day. Some of the most terrible things that had happened to me in my life had happened in here. But like the others I kept coming back.” Patrons at the Vine “had that helpless, destined feeling. We would die with handcuffs on. We would be put a stop to, and it wouldn’t be our fault. So we imagined. And yet we always being found innocent for ridiculous reasons.” As the narrators tells us, today became yesterday here, yesterday was tomorrow, and so on. Ironically, the bar’s name ironically echoes back to the New Testament here and John 15: 1-5:

I am the true vine, and my Father is the husbandman.

Every branch in me that beareth not fruit he taketh away: and every branch that beareth fruit, he purgeth it, that it may bring forth more fruit.

Now ye are clean through the word which I have spoken unto you.

Abide in me, and I in you. As the branch cannot bear fruit of itself, except it abide in the vine; no more can ye, except ye abide in me.

I am the vine, ye are the branches: He that abideth in me, and I in him, the same bringeth forth much fruit: for without me ye can do nothing.

By the close of the section, Jack Hotel has died of an overdose and the narrator has survived. “He simply went under. He died. I am still alive.” By chance or luck or fate, the narrator survives, “There was no touching the hem of mystery, no little occasion when any of us thought—well, speaking for myself only, I suppose—that our lungs were filled with light, or anything like that.” This hearkening back to light echoes back to Christ as the light of the world, and the ironic Vine suggests that even the most barren branch can bear fruit. Without the true vine, there is nothingness for him. So much of Jesus’ Son reminds me of Flannery O’Connor’s grotesque, Christ-haunted landscapes, where “the ragged figure who moves from tree to tree in the back of his mind” in Wise Blood. This very much feels akin to the narrator’s journey to find salvation, light, and grace and to escape the clutches of the false vine wrapped around him, if you will.

The narrative then leads us to “Dundun” where a murder has taken place. In this short section, Dundun has shot McIness, who dies without much notice in the back of the narrator’s car. It’s nonchalant and almost feels like the humdrum presence of the demonic or the dung heap. Blackbirds circle over their shadows. Jack Hotel, mentioned again after his death in the previous section, does drugs in the beginning and a remembrance of Dundun torturing Hotel near Denver is mentioned at the close. The section reads like the underworld of Iowa. “There’d been a drought for years, and a bronze fog of dust stood over the plains. The soybean crop was dead again, and the failed, wilted cornstalks were laid out on the ground like rows of underthings. Most of the farmers didn’t even plant anymore. All the false visions had been erased. It felt like the moment before the Savior comes. And the Savior did come, but we had to wait a long time.” The scene is a wasteland of the heartland, and the “rows of underthings” suggests the fates and destinies of the wasted people themselves, these scarecrows, waiting for salvation after plague, drought, and fire. Dundun is described like a fire-branded devil at the end: “It was only that certain important connections had been burned through. If I opened up your head and ran a hot smoldering iron around in your brain, I might turn you into someone like that.” The fire images here conjure thoughts of Prometheus, Milton’s Satan, and Melville’s Ahab. Dundun muses as they drive the “skeleton remnants” of fields that he wouldn’t mind being a hit man. He’s probably the darkest, most destructive figure of this wasteland.

In “Work” there are glimmers of salvation. The narrator and his girlfriend have been staying at a Holiday Inn. “We made love in the bed, ate steaks in the restaurant, shot up in the john, puked, cried, accused one another, begged of one another, forgave, promised and carried one another to heaven.” After an argument, the narrator hits his girlfriend and is beaten up by some onlookers. Then, he’s back at the Vine, meets Wayne, and heads out to strip the wiring out of Wayne’s old empty house for money. As they strip the house of copper wiring, an image of a red-haired woman appears on the river; she’s been pulled by a boat going thirty or forty miles per hour, and we learn that it’s Wayne’s wife. The narrator feels as if he’s wandered somehow into Wayne’s dream, and there’s a strange mystical sense about the moment. Wayne uses the odd word “sacrifice” as he buys them drinks at the Vine and as Wayne argues over cards, the narrator has a vision: “A clattering sound was tearing up my head as I staggered upright and opened the door on a vision: Where are my women now, with their sweet wet words, and the miraculous balls of hail popping in a green translucence in the yard?” The section is punctuated with odd visions and evocations of mysterious, angelic women, concluding with the bartender (Nurse), who “poured doubles like an angel right up to the lip of a cocktail glass, no measuring.” There’s the mention of a hummingbird, a symbol perhaps that challenging times are nearing the end and that you will find joy in your own circumstances. This is a crucial turning point in the narrative, as the narrator sobs and calls the bartender his mother. He seems to be seeking the assistance or intervention of the divine, perhaps the intercession of Jesus’ mother, the Virgin Mary. The reference of the bartender as “Nurse” leads into the next chapter, where work once again leads to greater revelations.

“Work” flows into “Emergency,” our only real glimpse of the narrator working an actual job before the final chapter. The narrator is working as an orderly in a Catholic hospital’s emergency room. He’s been working here three weeks (perhaps a symbolic nod to the trinity), but the attention in the opening page is on blood (Blood of Christ?). We meet Georgie, a fellow orderly, who steals pills from the cabinets. Blood is all over the floor, and Georgie points out “There’s so much goop inside of us, man and all it all wants to get out.” The section often feels confessional and miraculous to me—the central action occurs when Terrence Weber (played by Denis Johnson himself in the film adaptation) comes in with a knife in his eye, but doesn’t request for the police to be summoned, unless he dies. Georgie emerges inexplicably with the knife in his hand as the doctors debate a course of action, and Weber has nothing wrong with him. Georgie and the narrator drive around, at one point debating whether to go to church or the county fair. The most haunting section of the story comes when they hit a jackrabbit, and Georgie saves the babies inside the dead rabbit and hands them over to the narrator. Georgie feels like the white knight of these stories. The strange night they spend wandering around blurs the lines between reality and fantasy. A snowstorm engulfs them during their travels and the narrator asks, “Georgie, can you see?” The narrator then has this vision:

We bumped softly down a hill toward an open field that seemed to be a military graveyard, filled with rows and rows of austere, identical markers over soldiers’ graves. I’d never before come across this cemetery. On the farther side of the field, just beyond the curtains of snow, the sky was torn away and the angels were descending out of a brilliant blue summer, their huge faces streaked with light and full of pity. The sight of them cut through my heart and down the knuckles of my spine, and if there’d been anything in my bowels I would have messed my pants from fear.

Georgie opened his arms and cried out, “It’s the drive-in, man!”

“The drive-in…” I wasn’t sure what these words meant.

“They’re showing movies in a fucking blizzard!” Georgie screamed.

“I see. I thought it was something else,” I said.

This blizzard drive-in scene always captivated me, for it reminds me of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, as the prisoners are chained to watching the shadows on the wall, all the time believing what they’re seeing is real. Georgie’s intervention opens the narrator’s eyes for a minute, and then he drives that message home when he asks the narrator about the baby rabbits, which have been forgotten and crushed by Fuckhead. At this dark moment of revelation, Georgie asks, “Does everything you touch turn to shit? Does this happen to you every time?”

It’s a pivotal moment when the weight of the innocent, dead rabbits come to light—the illusions begin to fade. I consider Alice in Wonderland and Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit” in this section. Fuckhead has gone down the rabbit hole and the flickering images of his subconscious mind are finally beginning to hit bottom. He notes, “I could understand how a drowning man might suddenly feel a deep thirst being quenched. Or how the slave might become a friend to the master.” The image of the elk and the coyote in the field seems to foreshadow the strange watching of the couple at the close of the book. The elk waits silently with an air of authority—the ravenous coyote still jogs across the pasture. Maybe this is the spirit embodiment of owning up to addiction. Stand still and watch the white snow in the pasture, or keep plodding on, ravenous for more, looking and fading away into the darkened trees for another fix. Georgie’s last line of the section, when he’s asked about his profession is simple and straightforward: “I save lives.” In my reading this time, it’s the start of the Narrator’s salvation.

Like we’ve seen before, “Emergency” holds important keys for “Dirty Wedding,” which follows it. In this chapter, the narrator and his girlfriend Michelle have an abortion. We watch the narrator grapple again with the death of innocence, and to grapple with his confusion, he rides a train, watching families drift by through the windows. Fuckhead gets tossed out of the clinic, for being insensitive and cruel to Michelle after the procedure. He’s clearly making his way to the bottom by this point—he notes about the abortion protesters outside: “They splashed holy water on my cheek and on the back of my neck, and I didn’t feel a thing. Not for many years.” The scene that follows is a haunting one, as the narrators enters another train, all the while watching the snow out the windows and feeling the spectral presence of “the cancelled life dreaming after me. Yes, a ghost. A vestige. Something remaining.” The narrator decides to follow a man off the train and into a laundromat. In a short sequence, the man takes his shirt off and washes it and then confronts the narrator, noting he was on the train. “I turned away because my throat was closing up. Suddenly I had an erection. I knew men got that way about men, but I didn’t know I did. His chest was like Christ’s. that’s probably who he was.” Is this an ironic way of beginning the cleanout process? Christ in a laundromat? Is that where the rebirth cycle begins?

After getting back on the train, more hallucinations follow. Words like, “When I coughed I saw fireflies.” But there’s a strange moment of clarity which comes here: “I know there are people who believe that wherever you look, all you see is yourself. Episodes like this make me wonder if they aren’t right.” And it’s these swings from believing that he’s followed Christ into a laundromat to sensing he’s watching monsters dragging themselves upstairs at the Savoy that begin to move his vision away from himself. By the end of the chapter, Michelle has left him and committed suicide, and he ends the section with this haunting recollection about abortion, or perhaps about aborted love: “I know they argue about whether or not it’s right, whether or not the baby is alive at this point or that point in its growth inside the womb. This wasn’t about that. It wasn’t what the lawyers did. It wasn’t what the doctors did, it wasn’t what the woman did. It was what the mother and father did together.” And there, some bit of responsibility and connection starts to take root.

“The Other Man” and “Happy Hour” speed the narrator to rock bottom. First, in “The Other Man,” we see his meeting with the guy from Cleveland, who claims to be from Poland, and then his going home with the woman who had been married for four days. And finally, his pursuit of the aptly-named belly dancer, Angelique. “Happy Hour” appropriately ends in a bar in Pig Alley, Seattle. “People entering the bars on First Avenue gave up their bodies. Then only the demons inhabiting us could be seen. Souls who had wronged each other were brought together here. The rapist met his victim, the jilted child discovered its mother. But nothing could be healed, the mirror was a knife dividing everything from itself, tears of false fellowship dripped on the bar. And what are you going to do to me now? With what, exactly, would you expect to frighten me?” It’s rock bottom for Fuckhead—a disorienting place where he sits with a nurse with a black eye and remembers a moment when he almost killed a man at a library earlier on. It ends with the narrator considering that he may not be human, that he’s just taking bigger and bigger pills. It’s also his nod to Matthew 7:6 and not casting your pearls before swine in Pig Alley.

Mercifully, the next chapter, “Steady Hands at Seattle General,” takes the first step to recovery. The narrator shaves his roommate, Bill, and I can’t help but connect the character to Bill Wilson, founder of Alcoholics Anonymous. In the penultimate chapter, dialogue drives the story. Bill tells the narrator that he’s left wrecked cars behind—flashing back to where we began the ride of Jesus’ Son in “Car Crash.” After the narrator comments that the hospital is a playpen, Bill responds with the following:

“I hope so. Because I been in places where all they do is wrap you in a wet sheet, and let you bite down on a little rubber toy for puppies.”

“I could see living here two weeks out of every month.”

“Well, I’m older than you are. You can take a couple more rides on this wheel and still get out with your arms and legs stuck on right. Not me.”

“Hey. You’re doing fine.”

“Talk into here.”

“Talk into your bullet hole?”

“Talk into my bullet hole. Tell me I’m fine.”

The first part of Matthew 7:6 states: “Do not give dogs what is sacred…” As I concluded my reading of Jesus’ Son, I was struck by Bill’s line about the rubber toy for puppies. His reminder is that life is cyclical and finite, and that’s it’s time to step off the ride and leave the slovenly, cycle of addiction and dark holes behind, especially as you’re staring into one in someone’s else’s face, as you would in a group recovery meeting. This scene of looking into the bullet wound evokes the moment in the New Testament (John 20) when Jesus implores St. Thomas, the doubter, to examine his wounds to prove his identity. “Because you have seen me, you have believed; blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed” (John 20:29). The narrator, the perpetual doubter, has to look and acknowledge the abyss before his eyes and with his steady hands shaving Bill at Seattle General.

Losing Denis Johnson in 2017 was a massive, irreparable loss. It’s hard to imagine a writer with his depth, range, and originality. And, as I look back at this little masterpiece of a book on its 30th publication anniversary, I’m grateful for this dark, yet honest journey of an American drifter and dreamer, as he makes his way through the belly of the beast of his addictions, demons, and delusions, to be resurrected as a writer, worker, and weirdo. Denis Johnson tapped into something personal and eternal with Jesus’ Son, and it’s going to provide epiphanies for generations of readers to come. That’s something to be grateful for, a pearl of a book for a world in need of reunion, recovery, and redemption.

Ian S. Maloney is a Contributor at Vol. 1 Brooklyn and a Professor of Literature, Writing, and Publishing at St. Francis College in Brooklyn, NY. Ian serves as Director of the Jack Hazard Fellowships at the New Literary Project in Berkeley, California, Member of the Brooklyn Book Festival Literary Council, and Board Member for the Walt Whitman Initiative.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.