“All is illusion” is a mantra Roger Orr picks up on a spiritual pilgrimage to India but the meaning of the phrase gains resonance far beyond the metaphysical realm—nothing and no one in Orr’s world is what or who they appear to be. They are ever mutable and evolving as is the person at the center of this story.

The hero/subject of Bruce Wagner’s thirteenth book is called Roger, Roar, Rory, or one of a dozen other diminutives, nicknames, pseudonyms, and honorifics depending on who’s talking and what stage of Orr’s improbably storied career they’re referring to. Whatever his/her/their name, Orr contains multitudes without a single identity predominating long enough to be pinned down or defined. Orr is or has been a songwriter, actor, director, sculptor, and dermatologist. Tops in every field. A winner of Oscars, Grammies, Emmies, Tonys, and awards neither you nor I have ever heard of. A champion at the box office. All things to all people and too good to be true, or, perhaps, too true to be good.

At various times Roger Orr is a Jew, white, Black, male, female, and nonbinary and has love affairs with celebrities and commoners of every race and gender.

Growing up on the margins of Hollywood, it’s a world Wagner knows inside-out. But what separates Wagner’s project from the average celebrity tell-all or barely fictionalized roman á clef is a moral compass and an abiding affection for his creations, no matter how ugly or unseemly they may be. How ever low this or that attention-whore may stoop, Wagner is always there to help them back up on their feet. He believes in second, third, and thirty-fifth chances. The door to redemption and perhaps transcendence doesn’t lock on even the worst of his monsters.

Oral histories are typically devoted to the exploits of prominent people and events told by witnesses, acolytes, children, and others with firsthand experience. As a literary form, the oral history allows a writer or “editor” (as Wagner credits himself here) to dispense with exposition and filler that are necessary in traditional fiction. If the reader already knows the subject because they’re part of the culture, there’s no need for tedious introductions or scene-setting. There’s an assumption that whatever the reader doesn’t get they don’t get because they’re ill-informed and could get up to speed by accessing secondary sources. It’s an entirely different set of problems and expectations. But what if none of the “facts” stated by those who were allegedly there are true? What if the entire faithful account is false, a product of one writer’s imagination?

By interpolating Francis Bacon, Dick Gregory, Quentin Tarantino, Quincy Jones, Robert Gottlieb, Ram Dass, Allen Ginsberg, and dozens of others, including the novelist Bruce Wagner, into the the parade of voices telling Orr’s story, the portrait that emerges is not so much of a single entity as an entire culture. The speaking styles of all these luminaries are suspiciously similar to Wagner’s—never missing a chance at a pun, no matter how corny—but the mere invocation of their names allows the author to summon entire worlds in a reader’s mind without even a cursory description. There’s no need, for instance, to ape Bob Dylan’s cadence as he pays tribute to Roger Orr’s song craft. Dropping that name automatically calls up a cascade of sounds and images even for the most casual fan.

Wagner preempts comparisons by dropping in references to Zelig, Candide, Gargantua and Pantagruel, and other examples of literary fabulism himself. I’d add Art Pepper’s autobiography, Straight Life (dictated to and arranged by his wife, Laurie, thereby resulting in an oral history, more or less) and the art and life of musician/artist Genesis P-Orridge (whose attempt to merge with his spouse into an entity they called “pandrogyne” is not unlike Orr’s lifelong quest) as two other reference points that kept coming to mind as I read this book.

Because Wagner knows so much of the movie, music, and art history he skews and plunders for this polyphonic elegy to the dream factory he’s spent his life celebrating, frequent internet searches will be necessary for any reader fool enough to unravel fact from fiction in these pages. Was Fred McMurray a junkie? Did mass-killer Richard Speck grow breasts via hormone injections paid for by the state while behind bars? The more I read the more these and myriad other outrageous anecdotes became mere threads in a rich tapestry. No matter how lurid the details or off-color the language, it never comes off as mockery. Few have pureed, and julienned the purportedly real and clearly make-believe better.

By creating a character who can stand for most anyone who’s been ostracized or made to feel alien by American society, Wagner is proposing a kind of hopeful inclusivity that feels both generous and rare. In an era when artists are questioned for imagining their way into lives other than their own, he’s proposing an alternative. It’s not a longing for a reactionary return to a golden yesterday but rather an attempt to widen our perspective. All may indeed be illusion but few of us can live without those beautiful images.

***

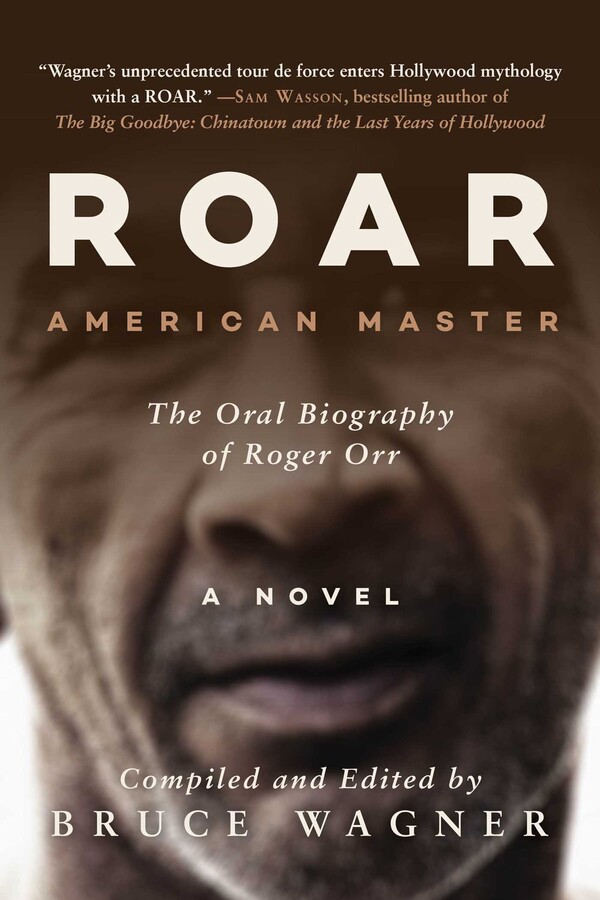

ROAR: American Master, The Oral Biography of Roger Orr

by Bruce Wagner

Arcade; 504 p.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.