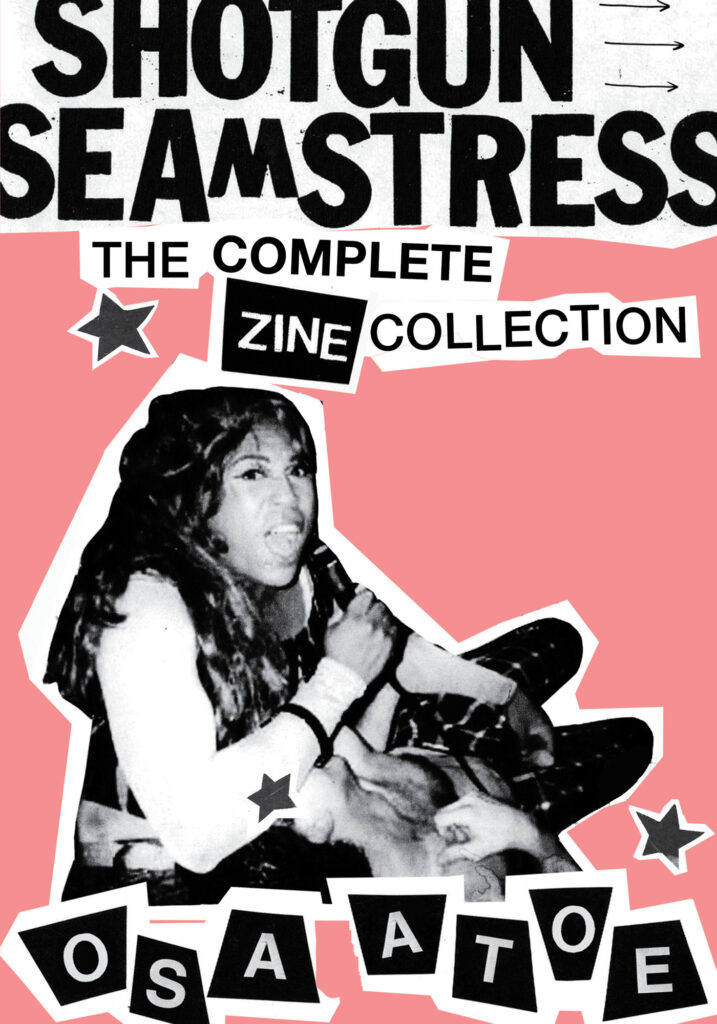

I grew up listening to punk rock, No-Wave, and various types of experimental music in the basement of my parents’ home in New Jersey, where the now old-fashioned stereo system was located: two large speakers leaning against the wall at an angle on bar stools, turntable and heavy receiver mounted on a wooden stand between them. I went to Bleecker Bob’s and Generation records on the lower east side, or a small record shop, Things from England, a few blocks from where I lived in New Jersey, to pick up the latest new wave and punk records. I was thinking of these early experiences when I picked up Shotgun Seamstress.

The book was a revelation, as it chronicled Black punk and outsider culture during the early to mid 2000s and opened for me new worlds of sonic and visual work. Inside the book, I found essays, interviews, book reviews, as well as fascinating articles on the punk rock scene in Brazil and Nigeria. The zine succeeded in created a space where Black outsiders and musicians were free to express their ideas on music, sexuality, metaphysics, politics, literature, and many other subjects. The world Atoe envisions in its pages is all inclusive. For her punk is a general aesthetic that applies to those who are marginalized. DIY rejected the glossy aesthetic of the popular magazine without the concern for wide distribution. For Atoe, DIY artists created zines not for money, but because they are passionate about what they do.

For the bands Cellular Chaos, Trash Kit and The Dirtbombs, to mention a few of the bands profiled in Shotgun Seamstress, “noise” was as important as any other part of the music. Jacques Attali’s Noise: The Political Economy of Music was useful to me as an examination of “noise” as a political tool. Attali writes:

With noise is born disorder and its opposite: the world. With music is born power and its opposite: subversion. In noise can be read tht: codes of life, the relations among men. Clamor, Melody, Dissonance, Harmony; when it is fashioned by man with specific tools, when it invades man’s time, when it becomes sound, noise is the source of purpose and power, of the dream-Music. It is at the heart of the progressive rationalization of aesthetics, and it is a refuge for residual irrationality; it is a means of power and a form of entertainment.

Everywhere codes analyze, mark, restrain, train, repress, and channel the primitive sounds of language, of the body, of tools, of objects, of the relations to self and others.

DIY punk was never about making money. Real pleasure doesn’t encourage capitalist production.

Atoe’s use of the word punk extended beyond the music, to encompass photographers, tattoo artists, and trans performers. In each issue included the statement: “Shotgun Seamstress is a zine by & for Black Punks, Queers, Misfits, Feminists, Artists & Musicians, Weirdos and the people who support us. This zine is meant to support Black People who exist within predominantly white subcultures, and to encourage the creation of our own.” For example, there is a portrait of the photographer Alvin Baltrop (1948-2000) in issue #2, which contained writings on the nature of class. His photographs of gay sex at the NYC Piers in the late 70s, were for many years ignored, while Mapplethorpe became the darling of the art world in the 80s. Alvin’s photos were raw, intense, personal, even graphic, but not stylized. He just used his camera to shoot what interested him. But succeeding in the art world is always a matter of who you know, how well you can network and play the art game. Atoe asks: “Why does so much art have to be filtered through the doors of white-owned, high-brow galleries before it makes it to the general public?” A Black homosexual man without these “white” connections, whose involvement with the men he photographed gave his photographs an intimate, personal quality, always had to face being ignored by the proverbial “gatekeeps.” Though recently there has been growing interest in his work.

The official history of punk is sanctioned by the ruling narrative, in books that repeat the same white male heterosexual bands over and over. In an interview for the punk zine, Maximum Rock N Roll, when asked why it was important to have girl bands, queer bands, and female-fronted bands, Atoe responds:

There are two reasons. One, that’s just what I like aesthetically. I like a lot of bands with female vocals in them. I sort of associate women playing music with starting from scratch and creating their own weird sound. I feel like that is something that belongs to punk in general but, I can think of so many bands that are all female or majority female, bands like Quixotic, Chalk Circle, of Raincoats that make a really interesting sound, really unique. Also, trying to focus on creativity versus technique. I mean, all these things are ideas and concepts that belong to punk in general but for whatever reason, due to my experiences of the kind of music that I found when I was finding out about a lot of punk bands, I just came to associate those ideas more strongly with girls bands especially probably because I came into punk learning about riot girrrl and bands like Bratmobile that had a super primal, really simple style that [was] really powerful and just kind of taught me the lesson that music doesn’t have to be technical to be good and you can find your own way.

Forget about the Sex Pistols, The Clash, etc., etc., Check out New Bloods, The Dirtbombs, Trash Kit, and Cellular Chaos and many of the bands mentioned in the book. Shotgun Seamstress creates an alternate history and corrects the record. There were the Slits, X-Ray Spex (Atoe interviews the lead singer Poly Styrene in issue #6) and a few other bands but not many with female members who were extensively documented and fewer female-fronted punk bands. Shotgun Seamstress documents the electrifying world of Black punk music, No-Wave (like Atoe’s great band, New Bloods, check them out on YouTube) and experimental rock, like Cellular Chaos, whose drummer Eric Edwards played with Cecil Taylor.

Atoe was also able to connect with punk bands in different parts of the US and abroad. She worked at providing food for homeless queer and trans kids and wrote flyers for events where she and others would teach musicians the technical aspects of a recording studio or if one didn’t know how to play the drums there was also a workshop for them. Atoe improvised a school made up of female black and queer punks who convened in an occupied house to play music, where they were free to express their desires and engage with each other in productive ways. It was never about how good a musician you were, or the clothes you wore. Here in the United States accreditation is everything, no matter how much one knows; furthermore, universities are now corporate entities who value profit over education. And we see with the various MFA programs a kind of standardization of writing and thinking practices which enforces a kind of uniformity rather than radical difference.

Shotgun Seamstress showed me that the punk aesthetic could encompass a larger field of Black music than I thought possible. In the first issue of the zine, Chris Sutton makes a powerful argument about the importance of Black people to the evolution of punk: “All great underground pop music comes from beautiful black people. The Punks were obsessed with Reggae & early Hip-hop, rich influences coming from huge Jamaican communities in London & New York respectively, and later post-punk latched on to the disco styles emanating from the black gay subculture.” It is rare that a book I read had such an impact on me. It opened for me a world that I did not know existed. And the book is relevant today in that it gives voice to Black punks and outsiders, a marginalized culture, and in doing so celebrates difference in a world that threatens to become homogenized. I could go on telling you how great this book is, but I’ll stop now. Just go out and buy it. You won’t be disappointed. The book will change your life. It might even inspire you to create a zine of your own.

***

Shotgun Seamstress: An Anthology

by Osa Atoe

Soft Skull Press; 368 p.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.