Earlier this week, I was interviewing the writer Jeff Noon when the subject of his past as a playwright came up. Noon’s far from alone in having one foot apiece in the worlds of prose and theater; Samuel Beckett is probably the best-known example of someone doing interesting work in both disciplines, but Cormac McCarthy and Michael Frayn also come to mind. New York has seen a few examples this year of stage work by writers best known for their prose, including BAM’s staging of The Wife of Willesden, a play by Zadie Smith and the subject of this review, The Brick’s production of Jesi Bender’s Kinderkrankenhaus.

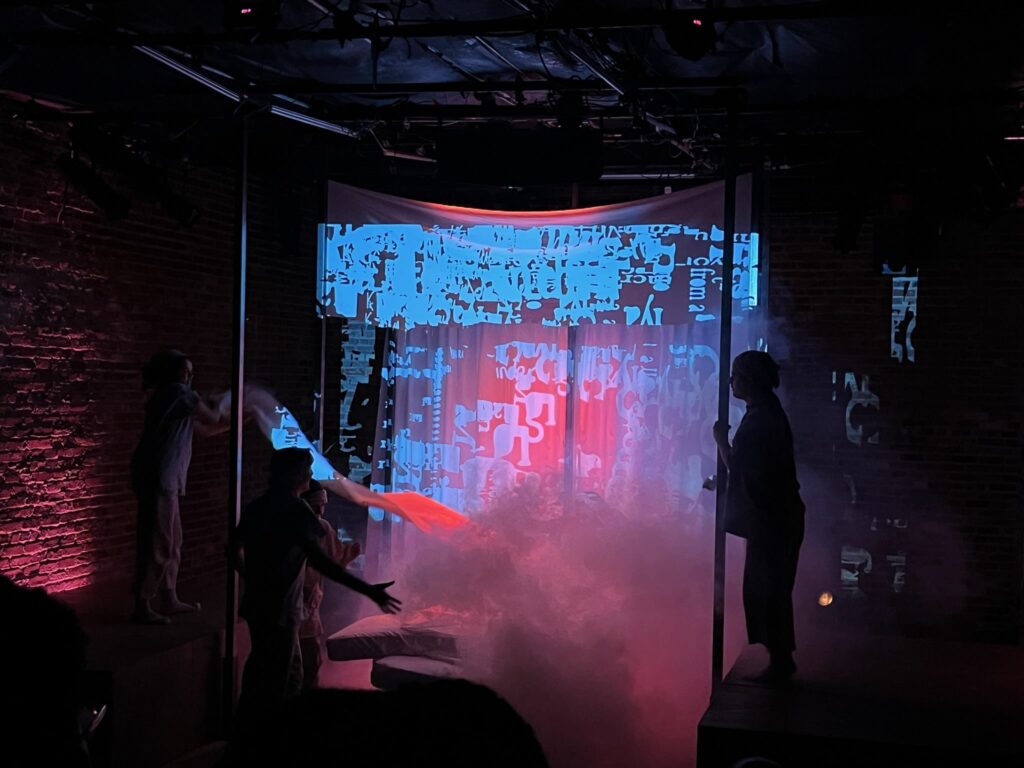

Kinderkrankenhaus is a play about a group of children who have been committed to some sort of institution; the doctor tasked with their welfare, Dr. Schmetterling, oscillates between genuine concern for her charges and a more authoritarian call for general conformity. The arrival of a new patient in the hospital, who takes the alias Gnome, becomes a catalyst for change on both individual and group levels.

When writing prose, an author can be as specific as they’d like about a character’s appearance — or leave things to the imagination. (Anne Garréta’s Sphinx, a romance between two characters whose gender is never specified, might be the apex of the latter tendency.) As Jared Joseph wrote of Kinderkrankenhaus last year, “We do not know Gnome’s given birth name nor gender; the only gendered character in the play is the doctor, she who wields a dual power of identification.”

Watching Kinderkrankenhaus is very different from reading Kinderkrankenhaus, in this respect. Here, the characters are played by actors, which at the very least means the presence of bodies, many of whom present as masculine or feminine. Kayla Juntilla’s performance as Gnome felt haunted by what the character can and cannot say about their trauma; still, the casting of an actor — of any actor — creates certain dynamics based on an audience’s expectations. It’s fascinating to think about a production in which the cast changes roles each performance — a kind of variation on the time Phillip Seymour Hoffman and John C. Reilly alternated lead roles in a production of Sam Shepard’s True West.

There’s another ambiguity that factors significantly in Bender’s play: namely, the setting. As Joseph wrote in his review of the play in book form, “It could be taking place now; it could be taking place in Nazi Germany; it could be both.” Joseph goes on to note that there are some solid pieces of evidence for the second option — including a plot development that takes place later in the play, as well as the surnames of several characters. That said, the casting of a diverse group of actors pushes back against that, at least somewhat — and, in The Brick’s production, made that ambiguity a little more unsettling.

In the weeks following my visit to see Kinderkrankenhaus, I read a harrowing article by Margaret Talbot in The New Yorker about a group of now-middle-aged people who had lived through a harsh experience of institutionalization in post-World War II Austria. Talbot points to one especially unsettling moment from the life of Hans Asperger, the doctor for whom a type of autism spectrum disorder is named:

Evy and I visited Herwig Czech, a medical historian in Vienna who, in 2018, revealed Asperger’s complicity in the Nazi regime’s eugenics policies. Heilpädagogik experts in Austria, Czech told us, had been eager to demonstrate the field’s compatibility with National Socialism, and also with the “strong authoritarian current” of Austrian Catholicism. Asperger had referred the most troublesome and mentally handicapped children to a Viennese institution, Am Spiegelgrund, where patients deemed “incurable” were killed.

I couldn’t stop thinking about this and how it related to Bender’s play — one in which Dr. Schmetterling’s focus is on trying to make her young charges appear to be more “normal,” lest they face a much bleaker fate. It’s a haunting thread that ran through the play and continued long after I left The Brick on a Friday night earlier this fall. And that’s the other thing drama can do: in its physical presence, it can expand out into the wider world, making it seem as though everything is a part of the work you’ve just seen.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.