My new novel, Sleeping With Friends, asks what would happen if memories of film watching were to become the only thing an amnesiac woman has left. And what if the film memories can reveal to her who among her friends has tried to kill her?

Combining film and the printed word is usually considered an act of crossing the streams. It’s true for the most part—the mediums are vastly different in what they require from language. The novelist struggles to write a raindrop in words. A screenwriter will likely be fired if they get more detailed than “It’s raining.” Reading is active. Watching is passive. Or is it that simple?

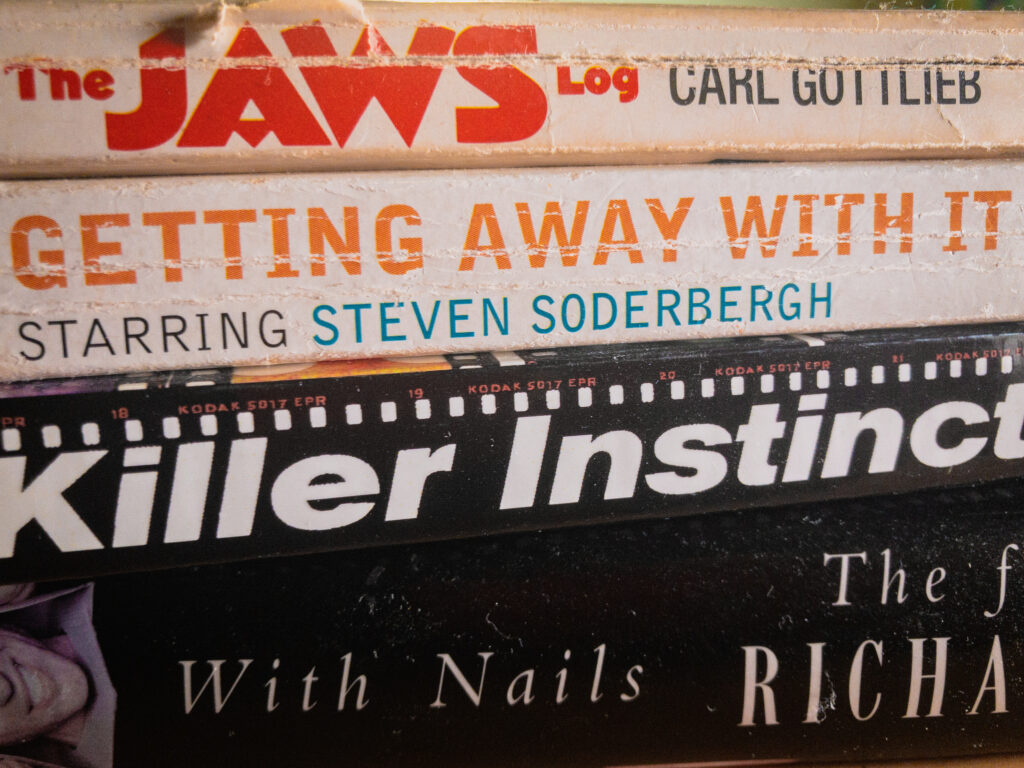

While one of the inspirations for my novel was how films can bring friends together, I’ve also long nurtured an obsession with books about how filmmaking can drive people into collective madness. After all, film sets are seething hives of resentment, exhaustion, and sociopathic behavior. And that’s on the good days. It’s when filming goes really bad that things get even more interesting.

Carl Gottlieb, The Jaws Log

The tormented story of the making of Jaws is so well known that it actually has been adapted, not as a movie but as the play The Shark is Broken (Ian Shaw and Joseph Nixon). The myth-making really began with Jaws screenwriter Carl Gottlieb’s making-of book from 1975. It helps that Gottlieb—a member of the improv group The Committee—is hilarious. He’s also unsparing in the ’70s details. Not many studio-branded making-of books casually mention the star was whizzing on coke during his audition. More than a quickie tie-in, The Jaws Log transcribes exactly how any film is made and how one particular film drove its cast and crew slowly insane. The book is still in print and on many a filmmaker’s shelf for a reason.

Julie Salamon, The Devil’s Candy

There are so many lessons in this autopsy of Brian DePalma’s Bonfire of the Vanities, but the most invaluable one is: adaptation is hard. A close second would be: satire is really hard. Writing at the time for the Wall Street Journal, Salamon itemizes, in granular detail, all the money and effort that can be thrown at a misfire A-list Hollywood production to try to make it work. (There are also novelistic detours, like the strange story of Bruce Willis’s identity challenged stand-in.) In the midst of all that bloat steamrolling under its own weight there are dissenting voices asking questions, often far too late. Is Tom Wolfe’s very-1980s book dated by the time the film is made? Is this script actually funny? Then again, warnings that go unheard under the din of a camera crane are key to any Hollywood tragedy.

Jane Hamsher, Killer Instinct

You’ll find this on a lot of film book lists but I doubt many have actually read this long-out-of-print scorcher of a burn book about the making of Natural Born Killers. In 1990 an unknown screenwriter named Quentin Tarantino optioned his screenplay to a group of young wannabe producers, including author Hamsher. As any writer who has been through this could guess, absolutely nothing happens. That is until Tarantino’s script for True Romance becomes a hot studio property and sets off his career. With Oliver Stone now taking over Natural Born Killers from the inexperienced producers, the making of the film becomes emblematic of everything that can go wrong when ego and fame are poured like gasoline over a development. Add in a seething writer being re-written by the director’s mushroom dealer, as well as two tag-along producers well aware of their barely tolerated status, and you will be endlessly entertained by a Hollywood that doesn’t exist anymore.

Richard E. Grant,With Nails

This generation might know Richard E. Grant for his appearances in Loki and Game of Thrones, but to me he’ll always be Withnail from Withnail and I, or Anaïs Nin’s gormless husband in Henry and June. The other British Grant of the 1990s also turned out to be an obsessive diarist and God-tier gossip. In his first volume of diaries, he recalls his entire early career and his first American appearances, like in the corny Warlock, and his histrionic turn in Bram Stoker’s Dracula. But it’s his miserable time making Hudson Hawk that is the witty heart of With Nails. As Grant relates—and similar to Bonfire of the Vanities—no one said “no” to any idea on set, no matter how expensive or stupid. Grant’s spirit cannot be crushed though, even by the grim location shooting in then newly capitalist Hungary. He bonds with Sandra Bernhard and together they stalk Sharon Stone through Europe as a campy pastime that, yes, would have made better a film than the one they’re acting in.

Steven Soderbergh, Getting Away With It

After a string of cerebral films like Kafka and The Underneath, Steven Soderbergh went deeply indie and autobiographical with Schizopolis, one of my favorite films of all time. The making of Schizopolis, and the director’s attempts to sell it on the festival circuit, are chronicled in what is ostensibly a book of interviews between director Richard Lester and Soderbergh. Through diary sections the book captures him at a crossroads. How long can he be last year’s wunderkind? Near the end of his efforts, Soderbergh realizes that making a surreal comedy about his divorce, starring himself, with half the movie done in language experiments, is not helping his career, even if it has freed him from his self-serious stage. After his lowest point —looking in at an Oscar party that he’s not allowed into only to see clips of his own Sex Lies and Videotape playing on screens—the reader almost weeps in joy at the studio ending when Soderbergh gets the job of directing Out of Sight.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.