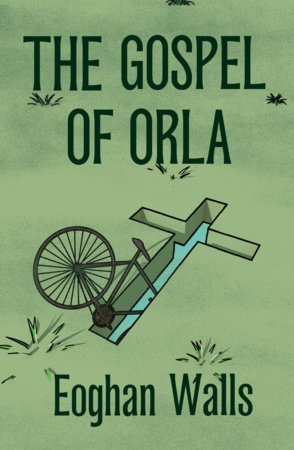

This recent novel by Northern Irish poet Eoghan Walls has an intriguing, Magrittian cover: it wraps around from front to back with a lively green backdrop, punctuated with sparse tufts of grass. Between the title and the author’s name on the front page is the 3D cutout of a cross. Unexpectedly, the cross is not centered and frontal, but slanted and on the ground, in the grass. Looking closely, it is possible to see a sliver of pale blue through it (another sky? another world?) and the silhouette of a bicycle entering it. I can’t think of a better way to visualize this enigmatic story. So much of Walls’ novel takes place outdoors, in the no man’s land that is the contaminated nature at the edge of urban areas; bikes are a big part of the action; there is a girl who metaphorically must carry a big cross of mourning and suffering on her shoulders and there’s a strange man who calls himself Jesus.

The Gospel of Orla takes place in our days in the village of Glasson Dock in Lancashire, England. Fourteen-year-old Orla McDevitt is troubled. Besides dealing with the cruel experience of adolescence, she has to process the recent death of her mother—who died of cancer only a few months before the story begins—while watching her father fall in the spiral of alcoholism and taking care of her little sister, Lily. There seem to be all the elements for a tearjerker, but The Gospel of Orla isn’t one because, despite these sad circumstances, neither the author nor Orla wants pity.

Our heroine is street smart, and she won’t back out down until she accomplishes her task. She is a resourceful, foul-mouthed, tough girl, reminiscent of Mia in the movie Fish Tank (2009), by acclaimed British filmmaker Andrea Arnold. Like the movie protagonist, she is certainly not going to sit around and hold her head while dramatic events unfold around her. Furthermore, the book also has many funny and picaresque elements: like Pinocchio, Orla must endure adventures of all sorts, interspersed with near-death experiences and magic elements, to grow up and become a mature human being.

When we first meet her, she is busy planning her second escape to reach Drumahoe, in Ireland, where her mother is buried and where her aunt lives:

I am taking the canals because nobody will look for me there. I got a book Traffic-Free Cycle Paths in the Northwest and could name all the rivers and villages I will pass through with my eyes closed. I left my phone so they can’t GPS me and if they see my bike is missing they will be, – She must be on the roads! which is bullshit because I will be on the canals. I have googled everything and deleted my history. By the time they have figured it out I will be halfway to Ireland.

Orla feels that she doesn’t have much to lose by leaving everything behind. She is going to miss her little sister, but she mostly feels estranged from her peers, hates going to school, and engages in petty crimes for the “buzz” that she gets from it. Her only friend, Jamie, recently got suspended. And, as if it that weren’t enough, social services are now on her case and threaten to put her in foster care.

Unfortunately, Orla’s path is blocked by blinding moonlight and a man that gets in the way. Without having gone too far and with her bike nearly destroyed and on the bottom of a canal, Orla heads back home with her tail between her legs, completely soaked in putrid water. How will she get to Ireland? She has no money for train tickets, and, in any case, she has been spotted at the train station and reported to her dad before. Will she walk there? When all seems lost, one night the stranger who caused the accident surprisingly shows up in her driveway to return the bike. Orla, armed with a knife, decides to follow him. From the previous encounter, she knows his name is Jesus: “Jesus bloody Jesus like the Jesus Jesus?”. She knows he is quiet, has a deep voice and a foreign accent; besides a pair of shorts, he only wears a tattered blanket.

Orla discovers that he lives in an abandoned barn close to the canal. She sees that he is surrounded by piles of dead animals (as it turns out, he killed some of them to suck their blood for nourishment), but he is capable of resuscitating them by breathing new life into them or by feeding them his own blood from his wrist: “He puts the duck’s beak in his mouth and the duck shakes in his hands. Like mad flapping its wings. The dead duck. Then the duck honks and shakes more and flap flap flaps and he puts it down and I see it walk away from him and it is not bothered at all waddling off in the moonlight with one quiet little honk.” This gives Orla a new idea: what if this guy could make her mother come back to life?

They get to talking. The man—part tramp, part vampire, part martyr—tells Orla that he found himself in a box at the bottom of the sea with dead people. It is hard not to see in this reference a touching tribute to the tragedy of immigrants who die daily while crossing the Mediterranean in trying to escape poverty and violence.

So I lay among the dead and taught myself to move. It might have been weeks or months. As I learned the use of my neck and my arms some memories came back to me. Songs. Words. Tastes. And one day I worked out how to move it all together and I pulled away from the bodies and swam through the hole in the box into the ocean. […] I swam up. The brightness above me was the light of day and when I saw that I remembered more. Heaven. Prayer. What it is like to breathe on land. And I knew that I had lain with dead people and that I had risen. I was the Christ.

Like Saint Thomas, Orla needs to touch with her own hands to believe. So, for starters, she asks to have her cat resuscitated. Walls narrates their encounters in a tone that endearingly mixes strangeness, tenderness, and comedy. Orla is intrigued, has lots of questions about religion, heaven, eternity, and death, but cannot quite grasp Jesus’s answers. Yet, even as she appreciates the supernatural value of this encounter, Orla also realizes that this Jesus is a lost cause: not presentable enough to take the ferry to Ireland, and also not believable by today’s crowds who are too jaded to even give him a second of their attention. Besides, he gets beaten up every time he tries to spread the word of God. And so, showing a sweet side of her that we already glimpsed in her playful moments with her sister, Orla patiently tries to improve Jesus’s public image, and teaches him how to use a smartphone to look for the best place for his second coming… and even how to bike. But she learns the hard way that, even if her mother came back to life, she couldn’t go back to Glassondock: she would have to stay with Jesus. So, Orla makes her last change of plans: she leaves the holy man with a circus, believing that in this way he will finally be able to reach large crowds.

The circular theme of the circus, which recurs at the beginning and at the end of the book, contributes to give this novel a suspended and magic atmosphere, suggesting once again the protagonist’s need to look for another dimension and linger a little longer on the threshold of childhood. The image of the sad elephant Fantasmo, who draws Orla’s interest since the beginning of the novel, almost becomes her alter ego: this creature too is trapped by society and needs freedom.

The poetic vein of Eoghan Walls’s debut novel comes out in these tender moments, in Orla’s drive to look beyond the black screen of a device to dig for the roots of her pain, and in her contact with nature—the backdrop of her escape—that provides serene breaks in the well devised, action-driven plot. But there is no room for much slush because Orla has no time to waste, and this is her story in the first person. And so, the writing fully becomes the character, and it moves quickly with her and sometimes spins out of control, like Orla’s breath when she has her asthma attacks, masterfully dripping with Gen Z British slang playfulness.

Despite all her suffering, we want to believe that this lively girl’s spirit will never be defeated, and by the end we all want her to have the last laugh:

The whole thing is crazy and I must be mad the whole way I have been living is bonkers. But the breeze is lovely and I like who cares. Who cares? There is lightning in the distance it could be over the sea or out on the rusty piers at Blackpool I can’t be sure which way is which anymore but the sky lights at the edges like there is a war on the other side of the world or a huge fire or some disease that could kill us all. But none of it matters because I have robbed a bloody elephant which is probably the biggest thing anyone has ever robbed in all of Lancashire maybe all the world and I laugh like a big stupid kid.

With its evocative writing and emotional depth, The Gospel of Orla leaves a reader wanting more. Whether it’s a sequel, a film adaptation, or simply another book by this talented author, I eagerly await what comes next.

***

The Gospel of Orla

by Eoghan Walls

Seven Stories Press, 240 p.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.