My Father’s Face

by Alex DiFrancesco

Olive skin.

*

I am scrolling mindlessly through Facebook when an article jumps out at me. In the accompanying picture, a woman has a thought bubble with nothing in it. The headline says the article is about people who cannot see pictures in their mind.

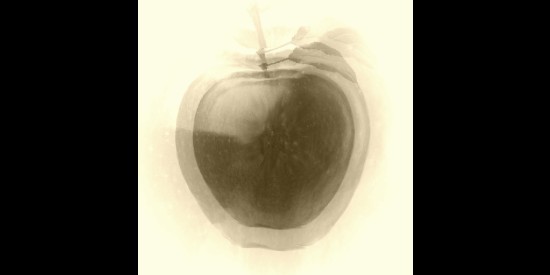

I am shocked. I pull up the article. The first line talks about how when directed to imagine an apple, most people see one in their mind. I close my eyes. Nothing. Smooth blackness, as there has always been.

*

Salt and pepper hair, balding on top.

*

When I was a small child, I was convinced that everyone around me could read minds, and they were being kind to me because I could not, keeping the secret of how their inner lives worked. Obviously, this is not true. Yet it is not that far off of the mark from reality.

*

Booming laughter from a wide smile. I cannot see this smile, or describe it differently.

*

Until I was thirty-seven years old, I assumed “the mind’s eye” was a figure of speech, and “visualizing” or “picturing” something consisted of calling up the details of it in your mind.

If someone lead me through a meditation exercise that called for visualizing a beach, my inner thoughts went something like this: there is sand, sand is golden, there is the crash of waves, there is a line that marks the tops of the waves from the sky even when the ocean and the sky are the same color. There are brilliant orange and gold and red sunsets. If you are walking down the beach, your feet leave prints deep in the sand.

Never once could I “see” this.

*

Stubble, often. Also salt and pepper.

*

I am a writer and a reader. A friend told me that her writing is like translating films she sees in her head; I cannot picture the books I write in my mind. I cannot picture the books I read in my mind, so I read for words, for structure, for sound. When I write am transcribing directly the words that have always lived in my head.

*

Cigarette smoke.

*

The word for this is aphantasia. A being anti- or opposite, phantasia being images, the imagination, phantasms of the mind. Someone who cannot see pictures in their mind. Around 2% of the population of the world is said to have this inner blindness. I feel somewhat scared and alone, reading about it as I lay in bed, until I realize this is about the same amount of the population who experience synesthesia, the blending of sense in the mind that creates color from sound, or sounds from color. I think about the words that have always lived in my head. How once, when I was young, I told a doctor I heard voices, because the words never stopped.

*

Long, large nose.

*

The things that shock me: you were all counting actual sheep; when you said, “The movie is never like the picture in your head” about book-to-film adaptation there was an actual picture; you can all call up real images of those you haven’t seen in years — such a gift.

*

Green eyes. The same green as mine.

*

I haven’t seen my father’s face in nineteen years. I have one picture. The only image of my dad I can see is a polaroid of him with cut-outs of Ray Charles and the Ray Charles backup singers after winning a ‘90s Diet Pepsi taste test at the grocery store. I don’t mean for the humor of this (which my dad would have appreciated) to take away from the fact: I have not seen my father’s face since he died.

*

Are these details enough? You all have such a gift, do you even know it?

*

My inner life isn’t lacking. I dream involuntary images, a common occurrence amongst aphantasics. I have always made up stories. I can memorize songs and poems better than most people. My mind is full of words, streams of them, memories composed of them, details that I force myself to store away that others might leave to their image-filled brains, letters I will write, books. I didn’t start writing by accident.

*

There are other people in this world who can call up his face at will. What will become of it when they pass away? What if, one day, I, the youngest in my family, am the only one left holding onto the memory of my dad. Will these details be enough then?

*

I study the picture of my father. Could I draw it from memory? Almost impossible. The words do not translate that way. Could I “picture” it if it were destroyed? Wide smile, olive skin, green eyes behind the smile’s squint, tan jacket, blue jeans, next to smiling Ray Charles.

But no, that is not a picture. That is the mind’s attempt to blunder through the memory of an apartment it cannot really conjure, but assumed no one else could, either. The bedroom is to the left, the kitchen to the right, the bathroom to the left.

*

“The world forgetting by the world forgot.”

*

What will, one day, happen to my father’s face?

Alex DiFrancesco is the author of Psychopomps (Civil Coping Mechanisms Press), and the forthcoming novel All City (Seven Stories Press).

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.