Holy Ground

by Jennifer Spiegel

Nothing To See Here

In June 2015, I was diagnosed with breast cancer. Surgery, Chemo, Radiation, Reconstruction, and More Surgery followed. Between then and now, I wrote Cancer, I’ll Give You One Year: A Non-Informative Guide to Breast Cancer, A Writer’s Memoir In Almost Real Time.

Unraveling

People ask how cancer has changed my life. Am I more religious? Have I forsaken sugar? Given up red meat? What’s with sex?

It’s in the book, but:

- I’m an introvert now.

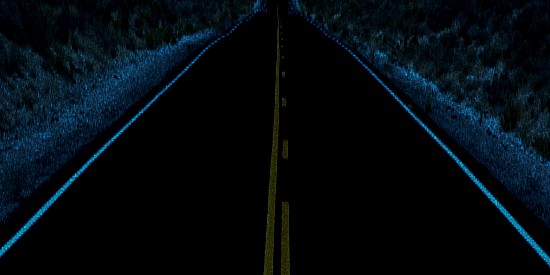

- I savor road trips.

The road trip part first: I’ve always loved travel. But now, I crave the jammed-in-the-car/free-hotel-breakfast/seven-hour-stretches–of-highway. I want to craft memories for my children. I want to unravel maps with them, holding hands in White Sands or before Renoir. I know life is a privilege.

But Introversion is new to me. I’ve always been extroverted, social.

Cancer has rendered me insular. There are medical reasons, like exhaustion, like incessant hot flashes. However, there are others: I just want to be with Tim, my husband. I’m a little nervous to be out there alone. I do it sometimes, venture into the world. I do writer things. I flew to Portland for a conference, went to Kentucky for a teaching gig even. But it wasn’t easy, and I missed my small world: family, pets.

(Do you know how many times Tim has attended my readings? Like, a gazillion. Because he’s had to go to every single one of them.)

So, I rarely go out past dark alone. Cancer has left me stumbling at dusk, longing for middle-age marriage, a cup of tea, Tim and his nightly bowl of cereal.

Unintentionally or maybe intentionally, I have made it a hard thing to maintain a friendship with me. With some trepidation, I admit that Tim is my world. Saying that—admitting that—frightens me. I love my steadfast friends, the persevering ones, the other introverts. And I’m wary of the vulnerability of my position, my reliance on some guy. Really?

Just the same: I’m an introvert now.

Cancer demanded of me that I get my house in order—because I was going to spend a lot of time in it.

Is this an essay on marriage?

No.

It’s an essay on writing under the cancer rubric.

It’s an essay on road trips.

It’s an essay on writing about road trips under the cancer rubric.

Slum Tourism

Perhaps it’s a good idea to ground ourselves in a loose theoretical paradigm.

Slum Tourism is treating poverty like a peep show. Have you heard of this before?

I looked it up . . . starting, of course, with Wikipedia (academic slummin’?).

In the nineties, I toured Harlem. Sounds awful in retrospect, but how else would I have seen the Abyssinian Baptist Church or the Apollo Theater back then?

I was with a mostly white student group, which included a beautiful black girl from Texas. All together, we stood on a corner, in the supposed-ghetto, a landscape of elegant brownstones, cracked pavement, and weathered storefronts.

Someone drove by and shouted, “Oreo!”

It took me a minute. To whom were they speaking?

To Nicole. Our friend, a woman, African-American, Texan (as exotic and “other” to me as Harlem).

Nicole was so Jackie O (she probably wore a pillbox hat and carried a little purse) that she only batted her eyes.

First slummin’ memory.

I guess I’ve gone slummin’ before.

I guess it’s part of my uncensored history.

Leslie Jamison

I never do hardcore academic work. But I love Leslie Jamison.

And she has informed my thinking on slummin’ and tourism. I first read her nonfiction during chemo. The Empathy Exams came out in 2014, but I picked it up in 2015.

First, think back. Remember being a kid before the TV on a Saturday morning rife with Sugar Smacks (that frog?) and “Speed Buggy” (did you know it was on for only one season?), and seeing a toddler in Ethiopia, naked, belly bloated, flies buzzing around lips, and some organization like the Global Famine Relief or Save The World Now announcing, End Hunger Today?

You’d stare.

You’d see it.

You’d wait for Scooby Doo or Shazam to resume.

Childhood in the seventies, eighties.

Poverty Porn: exploitation to illicit a response.

Just another part of this slum tourism business: voyeurism and otherness galore.

In The Empathy Exams and Make It Scream, Make it Burn, Jamison subverts this voyeurism of yesteryear by writing empathetically about different worlds, maybe misunderstood or unknown worlds. She speaks to people who genuinely believe their children are reincarnated war heroes. She talks to individuals, overwrought moms or undiscovered musicians or grownups with lousy childhoods, who forge out Second Lives in virtual reality, living as avatars. She talks with those who suffer from mysterious and possibly (not) phantom diseases. She explores the cacophony and garishness of Vegas; she thinks deeply about the life of a stepmom—because she is a stepmom.

It was an early text on cancer. The exploration of unknown lives.

Because my life was now an unknown life.

It was a book on writing too. Doesn’t she do what writers long to do? To go uninvited into worlds and make them their own, if only for a moment?

Since Jamison, I’ve given more thought to what has impacted my own gaze. Undoubtedly, hipsters (and gentrification?) are important.

Maybe—just maybe?—they’ve transformed slum tourism!

Consider the hipster.

With those unkempt beards, Goodwill threads, Holden Caulfield caps or Fedoras, they’ve become chic squatters. (Do I envy them their squatting?) Taking their knitting, their urban beekeeping, their taxidermy (so I’ve heard!), their fine coffee, and their complicated vegan diets, they might’ve made slummin’ obsolete. They’ve moved into cool neighborhoods. They’ve colonized slums?

The world is now OUR slum . . .

Thank you, hipsters!

(The connection with gentrification may require too much brainpower for me. But we could go there.)

Slum Tourism, with a dash of Leslie and a splash of hipster—along with a daily dose of Tamoxifen—paved my own Route 66.

Absurdity Tourism?

Route 66 calls me, and I’ve stood on a corner in Winslow, Arizona, not once but twice.

I’m dying to go to that Tiny House Hotel in Portland. It pains me that I never went to Bedrock before it closed.

So let’s forsake slummin’ and think about hitting the road in search of humanity—absurd, unruly, solemn, failing, beautiful, changing, questionable humanity. Humanity that gets cancer.

The Scientology Building on Hollywood Boulevard! (Free Shelly Miscavige!)

All of Amarillo, Texas! (We had a great time in Amarillo. Please visit Jack Sisemore’s Traveland RV Museum.)

Once, I visited Coney Island in search of two-headed babies; I think I saw a mermaid.

My personal coup d’etat, however, was Los Pollos Hermanos in Albuquerque, the chicken place in Breaking Bad.

Thanksgiving 2019

Destination: Inola, Oklahoma.

I love Tim’s family. After fifteen years, they’re my family too. I mean it. I really love them.

But Oklahoma? Couldn’t we meet in Boston? (Most of them are in Massachusetts, but Tim’s brother lives outside of Tulsa.)

We leave early one morning in the Honda. Tim immediately puts on Christmas music, apparently trying to send me into anaphylactic shock.

The girls (ages 12 and 13) act like they hate each other 80% of the time these days, but on road trips, they play elaborate games of Dumbo and Lady (from Lady and the Tramp). Those stuffed animals were the best toy purchase ever (Disneyland 2013). They will survive into the next decade, whereas the My Little Pony paraphernalia has been forgotten.

We pass abandoned, dying towns. Miami, Arizona. Beautiful in contemporary decline. Seymour, Texas. Desolation. How are communities abandoned? What happens that sends people packing? Where do they go?

Every time I see America, I think about how The Walking Dead missed so many opportunities for filming on location.

Every time I see America, I think about living without beauty. To dwell in unbeautiful parts. Dead parts. Dry parts.

I wonder at my choices. My desire for hustle, sprawl, frenetic clash and dazzle. I wonder, Did I make this choice, or was I just born into it?

We trail after Billy the Kid in Old Mesilla. We make footprints in New Mexico’s White Sands. We balk at aliens in Roswell. Sweet Roswell.

At each stop, Tim and I are Indiana-Jones-in-search-of-coffee-and-eccentricity. Show us a statue of Buddy Holly’s glasses. Let’s eat Lobster Bisque in Lubbock.

We spend three nights in Oklahoma.

I have lots to say about our semi-regular visits to see my brother-in-law and his family. I seem to unintentionally come off as this sharp-tongued City Slicker who has no clue how to walk through a dirt yard.

Once, my Boston-born father-in-law and I exchanged “a look” when we couldn’t find a Starbucks within, like, a three-mile radius of the “farm.” I guess, it’s a farm. They have poultry.

Once, I put my foot in my mouth when I declared that Highway to Heaven was the dumbest show ever. (Tim still hasn’t forgiven me for this.)

However, the real division is present, but undiscussed: my husband’s own North and South. We are the Protestants. They are the Catholics. Franciscans! This separation of faiths in the family happened before my arrival on the scene. They just went in different directions—these Irish boys. A Sinn Fein/IRA cease-fire, implicitly present. But they don’t argue religion.

This has always struck me, because, well, there’d be arguing in my family.

The Franciscan contingent keeps pets outside, and Tim tries to convince me of the sheer joy a dog has running in the woods, tail flying in the wind. I remain unconvinced.

Their neighbor’s daughter joined a cloistered convent. She’s 16 and she’ll be a nun. Cloistered, she doesn’t leave the convent. Ever. Even to get food. (Apparently, there’s another nun who does the shopping.) There’s a partition between her and visitors. Her life is supposed to be wholly devoted to prayer. I mean, she could leave if she wanted. But there she is, 16. I am simultaneously awed at such conviction and enraged, holding back an outcry, my self-righteousness coupled with righteous indignation. This child! This girl!

However, Catholics and Protestants fully unite over Mr. Rogers’ saintliness.

We see the movie on Thanksgiving Day. (Some see Frozen 2, others choose A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood.)

My sister-in-law asks me on the following morning, “Are you still thinking about Mr. Rogers?”

I am! “Totally!”

(He was a Protestant, I resist adding.)

But we share our Mr. Rogers’ lessons: how attentive he was to the individual moment, how deliberately he lived.

Mr. Rogers lived in his moment fully.

We go to an art museum; Tim says this is for me.

And my niece is tall, lovely, an Okie, also 16 like the cloistered neighbor. She spouts admiration for Kanye West’s conversion (which I pooh-pooh). She says, “I’m very passionate about this.” She sings the Chick-Fil-A song from Jesus Is King. She delivers political riffs, telling us about her MAGA hat. I hold my breath. Later, Tim, touching my shirt, whispers, “You’re all sweaty from talk of Trump.”

In truth, she reminds me of me at 16, but I had a different Kanye and wore a different hat.

But I think about my children, and I deliver tirades telepathically: Girls, we love Lindsey, lithe, Catholic, fervent, faithful. But you are not cloistered and you will not be cloistered and you have seen this America that they say needs to be made great again, and greatness has more to do with Native American ruins in Old New Mexico and that bakery we ate churros at in Roswell and bony horses in impoverished Texas. It even has more to do with alien crash landings and Chick-Fil-A. America is this hashtagged landscape, this broken territory of run-down gas stations and displaced people and the Bob Dylan Art Show we saw next to the Dorothea Lange photos of the Great Depression in Tulsa, of all places.

I practically shout, We Are Not Cloistered!

On road trips, I often pontificate about America.

Going home, after our Mr. Rogers’-imbued visit, we visit the oldest zoo in the southwest (Alamogordo, New Mexico.)

We accidentally pass Steins, a ghost town—a new forever regret.

I finally see The Thing off I-10. Overrated.

We eat at Popeye’s. Pretty good.

Our trip, voyeuristic, cancer-haunted, annotated and insular.

Ethics

Is this fixed gaze objectification, exploitation?

I remember Dachau in 1990. A former concentration camp in a quaint town near Munich. No bones, no ashes. Whitewashed, mere echo chambers.

Should we, college kid backpackers, have gone inside, or should we have turned abruptly, refusing to see, never memorializing, maybe even razing that provincial town to the ground?

China in 1997. Robin took me as her “writer,” when she launched Girls Global Education Fund. Really, I didn’t do anything. Except steal stories for later.

Were those rice paddy-enmeshed villages dying? Would entire dilapidated villages disappear like Venice, but without fanfare? And what of my writerly wanderings? What of our Shanghai rushes to McDonald’s, which we sought like refugee centers, our comfort in the Big Mac announcing our U.S. citizenship? Where is the morality in my Guangzhou market strolls, as I photographed hanging dead animals?

Soweto in 1997. Shanty towns. Apartheid ruins. But you don’t understand, I’d insist. South Africa was my heart, soul, beginning, end. But what can I say about horseback-riding in Swellendam or wine-tasting in Stellenbosch? Dear Lord, was my participation in the braai a Crime Against Humanity?

Cuba in 2004, an education visa. No Cubans were allowed inside our Havana hotel, except for employees. We were on a school trip, and our rooms had CNN—but across the way, ramshackle apartments were lit-up like ghetto dioramas. One day, a tsunami might wipe out the whole city. These buildings would be swept into the sea.

The Spanish teacher was cute, Mexican-American. One night, coming back from dinner, Lisa was stopped in the lobby. No Cubans allowed! They apologized profusely, not meaning to mistake her for a whore.

But the final word: The Jewish Cemetery in Prague, thirty years ago. A fairytale city with drawbridges, cobblestone, and swans (that bit!). The graveyard was breathtaking: dense, medieval, layered, disorderly. It reeked of meaning, saying, Life is for the living, death is for the dead.

I remember thinking, This is how to acknowledge the value of life.

Road Trip

We are decidedly uncloistered.

Fondling the living, their artifacts.

Gazing upon the world in aching adoration.

We do not traipse over graves.

Rather, we declare, Your World Is Holy Ground.

An Essay About Cancer

We take epic road trips now.

I’m introverted.

Maybe the epic quality is in direct proportion to my insularity: a way of compensating.

Like Mr. Rogers, possessing individual moments.

What I mean is: I’m living on borrowed time.

My time is borrowed.

Sometimes I mention insomnia.

My flesh on fire.

My body ravaged.

My body is the Jewish cemetery, the Chinese village.

My body, a shanty town.

I say to my children, Girls, Your World Is Holy Ground.

Your World

Is

Holy Ground.

Jennifer Spiegel is a writer with four books and a miscellany of short publications, though she also teaches English and creative writing. Her two latest books were CANCER, I’LL GIVE YOU ONE YEAR: A NON-INFORMATIVE GUIDE TO BREAST CANCER, A WRITER’S MEMOIR IN ALMOST REAL TIME (a memoir, which is not about eating kale) and AND SO WE DIE, HAVING FIRST SLEPT (a novel). She lives with her family in Arizona. For more information, please visit her website.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.