All That Hunger

by Kathe Koja

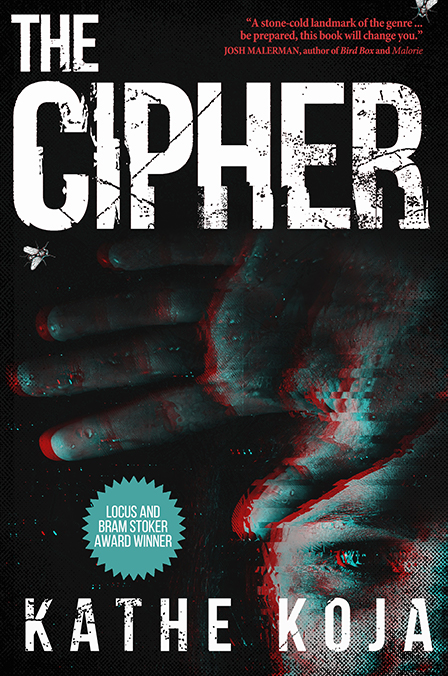

If you write a book about a bottomless hole that appears in a cruddy storage room floor, and call it the Funhole (the hole, not the book, although the book was briefly titled The Funhole until its original publisher insisted on a title change to The Cipher), you are going to get asked a lot of questions. Some of them will be predictably droll, some will be existentially thoughtful, and the great majority of them will be about that hole. Specifically, what exactly is it, a monster? a process? a Freudian metaphor? And what exactly happens in there, why do horrible things—transformative, absolutely, but uniformly horrible—happen to anything that gets too close?

I did write that book, and when I was asked those questions I mostly did not answer them beyond the answer everyone hates to get from a writer: It’s not about what I think happened, what do you think? And even though that is still my favorite and most authentic answer—because I do want to know what you think, it’s one of the main reasons I wrote that book, or any of my books: to create a conversation with readers—I now have a different answer, one that’s more satisfying, in several senses of the word.

The Funhole is hunger.

Consider all the different ways we can be hungry: we can want a meal; we can feel ill from lack of food, or actually become ill, we can perish; we can yearn for a particular taste, whether it’s Nana’s special soup or Twizzlers or petites madeleines; we can be surfeit already, but still eat more, and more, from boredom, from sadness, from compulsion. We can harbor other compulsions, too, to consume what is patently not food; ask an ER doc sometime about that.

Now take bodily sustenance completely out of the equation, and consider what we can be hungry for, a list too long even to compile, but let’s try: love’s the big one, with money right behind, or any of the zillion useful or useless things that money can buy. Success, security, freedom, control, the victory of our friends or the downfall of our enemies, or both; or all of it. What’s the last thing you wanted, really wanted, with a palpable need, something that kept you up at night? Something that would not let you rest? Did that feel like hunger?

Now think about what might be hungry for you.

It doesn’t have to be a person, although it usually is; it doesn’t even have to be sentient. And it certainly doesn’t have to be benign. Tumors are hungry. So are viruses. (Death never struck me as being particularly hungry, even though we so often see the Grim Reaper in skeleton drag. Death ought to be the one entity that is never hungry, every day must be a cosmic buffet for Death.) Do you ever think of yourself as delicious? As necessary to another’s real survival? How about being eaten, emotionally, alive?

Now think of the process of hunger itself. Does it begin with a lack, a negative space, a loss, an ache? Is it one cell complaining to another, is it a broken heart weeping in a corner, is it bleaker or more basic, is it not the most basic drive of all? What’s hungry wants to be fed. By definition. How is that wrong? How can it be wrong?

Now take a step back, several steps, step to the far rim of visual consciousness and imagine what, if anything, hunger might look like, if it could be seen as itself, if it could wear a containing shape? Would that shape not be simple? Would it have anything to hide? could it hide itself, a hunger as primal as that? Would you not know it right away, immediately, smell it even, would you not understand that what you were seeing, what you stood before—careful, not too close—was something as close to you as your own insides, something that you knew, something that might feel at first like something awful, but then—Then you might look at the floor of a cruddy storage room and understand why you are there, understand what you need, what you really hunger for.

Beside me, her whisper: ”Look at it . . . Wouldn’t it be wild to go down there?”

And me, on cue and by rote, “Yeah. But we’re not.”

There’s the answer. Now you know.

Kathe Koja writes novels and short fiction, and creates and produces immersive fiction performances, both solo and with a rotating ensemble of artists. Her work crosses and combines genres, and her books have won awards, been multiply translated, and optioned for film and performance. She is based in Detroit and thinks globally. She can be found at kathekoja.com.

Editor’s note: this essay is part of Koja’s online book tour for the new edition of The Cipher. Publisher Meerkat Press is also holding a raffle for a $50 shopping spree as part of the tour.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.