All the Daemons in Paradise

by Mary Burger

I had a skein of yarn—it was nice yarn, a silk-linen blend, hand dyed a deep orange-gold—that I’d mishandled and tangled into a mess. It was a rookie mistake. I’m not a knitter or a seasoned yarn wrangler. I was in the midst of a fiber arts project, and I’d bought the yarn to embroider a piece of wool felt that I’d made. I unwrapped the skein and pulled the loose end, and almost immediately had a snarled mess.

The yarn store, a fervently curated local shop, had offered to let me use their ball winder, a gadget designed to prevent this kind of thing, but I’d said no thanks. I was used to the acrylic yarn I’d crocheted with as a child, that came in machine-wound skeins with an end that pulled smoothly from the center and never tangled. But hand-wound yarn isn’t so facile.

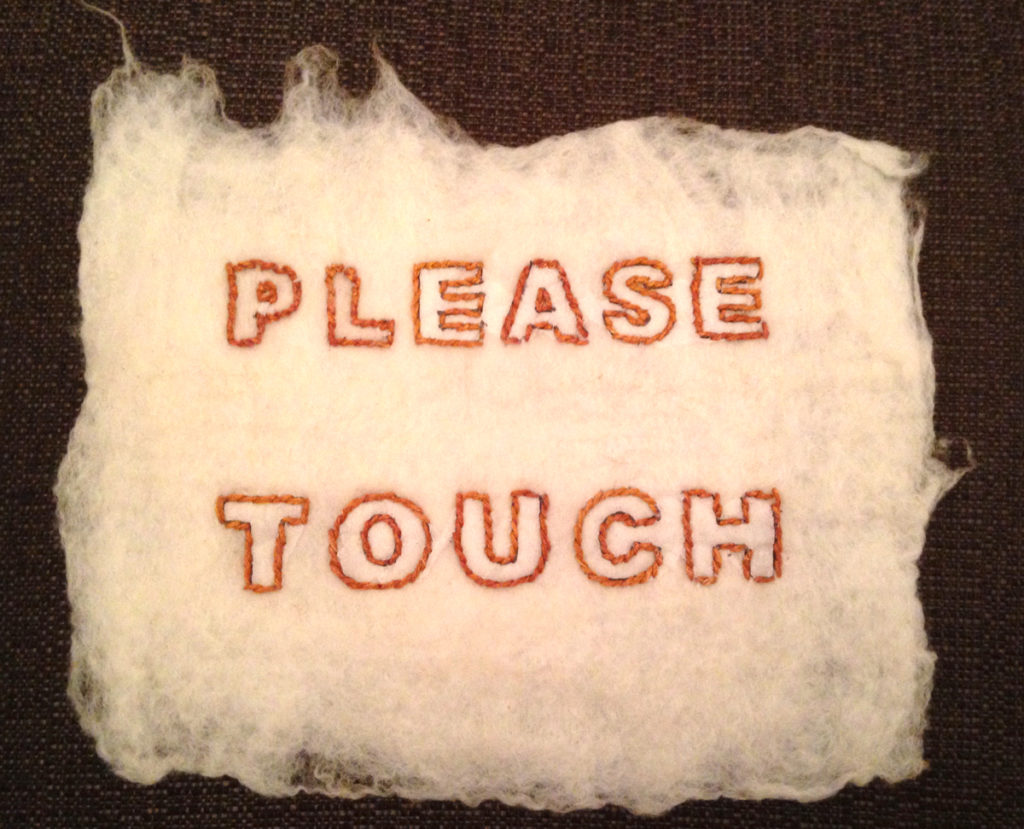

I teased out enough yarn for the embroidery—PLEASE TOUCH, in inch-and-a-quarter-high block letters outlined on a piece of natural white felt. It was the title piece for my show that would open in early December 2019 at ArtemisSF, a San Francisco project space for women and genderqueer artists. I wanted to use the tactile properties of fiber works to create a space of intimacy, where touch stood for nurturance, empathy, connectivity. From my artist statement, “Amidst the cacophony of our political crises, the ever-rising tides of violence, exploitation, and extermination, I want to change the terms. I want to create a space where vulnerability brings strength, not fear.” I finished the embroidery and tried to roll the tangled yarn into a ball. I stopped when the ball was less than an inch around, and the tangle of yarn still the size of a cat. It seemed undoable.

The first COVID-19 cases had already occurred, but hadn’t been identified as such. It would be another month or so before the disease would come onto the global radar, after which touch would have a new set of associations. Right then I wasn’t thinking of hand washing or social distancing or antibody testing. I was thinking of the emergencies that we’ve known about for years—the white male supremacist apparatus that enmeshes us, and its bullies who strive to outdo their own cruelty each day. The carbon emissions-based economy that ruins and ruins and cannot find a way to stop. The disposed and dispossessed who line the streets with tents, in the shadow cities that grow and grow. I wanted to shift my perspective, not to turn away from it all but to find a way of looking that offered possibility instead of defeat. PLEASE TOUCH was my invitation to others to join me. Most of the works in the show were hung on the walls away from viewers’ hands, the way that art galleries dissociate art from touch. But I laid the embroidered piece on a table for everybody to pick up and handle. I wanted a way for people to have a tactile experience. To feel the dense, matted fibers of this simple textile. To imagine the primal gestures used to create it, the same gestures used a thousand or five thousand years ago.

Most of the felt pieces had simple geometric patterns, made by embedding darker pieces of wool into the white backgrounds. The patterns were irregular—a grid with a few squares missing, a block of parallel lines with one line an odd length. I wanted to show intention but also intention’s tendency to get derailed. There was a second group of pieces, collectively titled Hindsight, made with broken car mirrors sewn into handmade silk pillowcases and hung together on a wall. Salvaging the useless, treating trash like something precious, seeing the mistakes of the past and valuing them for what we can learn, for what we can do better next time—this was a counterpoint to the felt works, tracings of the history that underlay our current crises.

The show closed on January 26. By that time China had reported the first coronavirus death, and there were cases in several East Asian nations and the US. Even so, the disease seemed containable. Confined to particular chains of contact. At the show’s closing, people crowded into the small room, shared food and drinks, passed the PLEASE TOUCH piece from hand to hand, shook hands, hugged—an ordinary gathering. A few days later the World Health Organization declared a public health emergency. But they didn’t use the word. Pandemic, from the ancient Greek, pan + dēmos, “all the people.”

In early March I left home for a writing residency at the Banff Centre in Canada. I’ve been working on a book, a memoir that’s in some ways about the impossibility of memoir, about the aporias and lacunas in memory and family history and my own understanding, the interpretive reaches that slant every personal narrative. The residency was only for two weeks, but I hoped it would be time enough for me to solidify the book, to get a sense of its eventual arc.

The trip meant getting on a plane to Alberta, moving into a residence hall, eating with others around a large table with food from a buffet—things that were still ordinary, though now accompanied by cautionary public health posters and hand sanitizer everywhere. The virus was on every continent except Antarctica. The US had recorded its first death from what had now been named COVID-19. My partner Aaron thrust alcohol wipes and zinc lozenges at me as I left home, extracted promises from me to be careful, careful, careful, to wash my hands continually. His worry wasn’t baseless. I have about half the lung capacity of a healthy adult, due to a long-ago illness. I have underlying conditions. Somehow, his concern grounded me, made me less worried instead of more—is that what love does? I’m not a worry-free person. But my worries tend to the absurdly banal—did I remember to take out the garbage?—or the impossibly huge—can I relieve my sister’s lifelong depression? For actual, clear-and-present danger—if you get the virus, you could die—I seem to trust the machinery of precautions and regulations. Maybe it’s being raised Catholic. The Catholics love a rule, a little tax you pay to God to keep you safe.

At first the residency seemed like a place apart—that was its purpose, after all. The virus had taken over news and conversations, but stay-at-home orders hadn’t started yet in North America. There were two known cases in Alberta. It seemed like our small mountain town might be outside the path of the storm. Then on March 11, the WHO said the word. Pandemic.

I want to say, Pandaemonium. The word Milton made up, from the Greek pan + Latin daemon, “the place of all demons”, the place where Satan held council in Paradise Lost.

We felt the avalanche of the WHO declaration a few days later. On March 16th, as the second week of the residency began, the town of Banff declared a state of emergency and closed everything non-essential. The Banff Centre cancelled all programming effective immediately. Our room and board would continue to the end of the week, to give us time to make travel plans. Almost everybody wanted to leave right away. Our group met up in the campus bistro that night to say goodbye, crowded together on sofas around low tables, sharing a last meal. We bonded over the calamity, but we were slow to pick up on the new rules. The next day the bistro removed the couches and left only a few tables and chairs, six feet apart. The day after that, the bistro closed.

I was one of the few who stayed to the end of the week. Aaron was planning to drive up and meet me. We’d made the plan months before, as soon as I’d been accepted to the residency. Even now as the world was shutting down, we wanted to stick to the plan. To slip through the fence for a minute, to have some time together far from home. A road trip would still be safe, right? Alone together in the car? We’d go deeper into the mountains, to a glacial lake we’d visited before. We’d stay at the lake’s edge for a few days in the storybook hotel there. On the way back we’d take a meandering route, stop at whatever motels were still open. Quarantine honeymoon. He had the car packed, was about to leave home the next day, when the border between Canada and the US closed.

I felt my body swept up like a small tree in the avalanche.

We’d known this could happen. We’d seen the thundering cloud of snow heading toward us. We skyped the morning the border closed. As his head bobbed up on my screen, I felt my heart rate slow and my voice get steadier. We agreed—if Aaron couldn’t come, I’d go on my own. At the frozen lake I’d breathe the crystalline air for both of us, watch the sunlight climb from one peak to the next, before I’d head back for the long shelter-at-home.

The lake had a backstory for us. After we’d gone there the first time, we’d learned that Aaron’s great-grandparents had been there one summer almost 100 years before. They’d gotten married in Oakland in April 1919, just months after the Spanish flu pandemic had battered the Bay Area. His great-grandmother had volunteered with the Oakland Red Cross to treat flu victims. His great-grandfather’s sister had caught the flu and died. A few years after that, the young couple had taken their road trip to the Canadian Rockies.

The uncanny family symmetry of road trips and pandemics was part of what drew me on. But also, I just didn’t want to give up. If it had been unworkable—if the lake hotel had closed, if Canada had ordered US travelers to go home—I was ready to fold. But there was still a crack in the door. Seeing the lake now would be like seeing it at no other time. In a normal winter it was crowded with tourists who came for the skiing, ice climbing, dog sledding—all the attractions that were now shut down. Only a handful of people would be there, walking the nearly empty trails, skating on the frozen lake. I wanted to be one of them.

I rented a car and drove higher into the mountains, then threaded through dense pine forest on a narrow road. Around a curve, the hotel appeared against a backdrop of steep peaks, the lake behind it blocked from view. Inside the hotel’s arched doors, the lobby was quiet as church. An extravagant spray of fresh flowers sat on the center table. The desk clerk, positioned several feet behind a socially-distancing velvet rope, welcomed me with courteous patter. She never broke character, though I kept expecting her to ask, Why are you even here?

Upstairs in my room finally, I dropped my bags and went to the window. The snow-covered lake lay below, a broad, flat arrowhead wedged into the cleft of the mountains. The glacier spread over the peak on the far side, catching the final light of the day.

I went out every morning, wrapped up in wool leggings and jeans, a scarf and a flap-eared hat, and padded boots shaped like loaves of bread. I went out when the sun was blinding bright and when the air was thick with snow. I walked to the lake’s end every day, about a mile, to the frozen waterfall that hung from the cliff like a ropy blue curtain ten stories high. Sometimes I was the only one on the trail. Other times I passed a few people heading back, some on snow shoes or cross-country skis. I stopped every hundred feet or so to crane my head around, to see how small the hotel was getting behind me, how close I was to the glacier and the waterfall. I snapped pictures constantly. But it was the things I couldn’t photograph that I want to hold onto. The snow squeaking under my boots. My breath short from the thin air. My cheeks chilled above the edge of my scarf. The silence whenever I stopped, except for a soft wind in the trees. The giant shadow play on the lake’s blank surface where the sun cast the mountains’ forms. The mountains that reached a thousand feet high until my sense of scale gave up. I turned in a slow circle and the mountains got tiny as I got huge. I held the scene in the palm of my hand like a sugar bowl. Above the pines, whole blocks of mountains were striated in horizontal lines dusted with snow, giant mille-feuille of pastry and cream, layers of limestone laid down millions of years ago on an ancient ocean bed, then pushed up into peaks like a rug bunched up on a floor. I zigzagged between the gigantic and the miniature, reaching for a way to hold on.

The skating rink was at the end of the lake near the hotel. Every day or so the grounds crew drove a snowplow onto the ice to clear the new snow away. Seeing the truck drive back and forth across the lake, proving the almost comical strength of the ice, was one of the lake’s delights. The rink was big enough for a few dozen people, but it was dwarfed by the rest of the lake stretching beyond it and by the mountains tilting up on all sides. I watched the skaters from the window in my room. Some were wobbly and some were expert, but each one goaded me, One more thing you need to do before you leave. I borrowed skates from the rental shop, high-tech hockey skates that were exciting and embarrassing at the same time. On the rink I swiveled around on the short blades, trying to find my balance. I had learned to skate on indoor rinks in figure skates with toe picks, novice skills that meant almost nothing here. The ice was rough and mostly buried under three inches of snow—the snowplow hadn’t been out that day. Only one other skater was there, a boy of about 10 with a hockey helmet on. He skated in calm, sweeping curves, never changing his pace or his footwork, as if he was just out for a stroll. I tried to picture him in a frenetic game of hockey, wondered if his Zen calm served him there. I tottered and wobbled and tensed to stay upright, afraid equally of the bruises and the embarrassment if I fell down. Eventually I mustered enough coordination to glide for short lengths instead of shuffle, and made a few laps around the rink. My heart pounded, my breath caught raggedly, I sweated under my layers of clothes—skating was, it turned out, an exertion, not a quiet place in the mind. I left the rink flushed with triumph, as if I’d finished a race.

On day four it was finally time to go. I crammed things into my suitcase and cursed the extra clothes I’d brought and the bread loaf boots I’d have to wear all day because they couldn’t fit back into my bag. As I was leaving, the snowplow started to clear the morning snow off the rink. The fairy tale went on, enchanted forest lurking with demons, the Brothers Grimm.

I drove east the few hours to the airport. Inside, a sprinkling of passengers rolled bags through the polished corridors. Ticket agents chatted together or sat idle. For once the restrooms were empty. The food court, newsstands, gift shops were all shuttered. People moved in wide arcs around one another, leaving cushions of empty space. There were masks, lots of them, but still not on everyone. Sometimes when I had to talk to someone, I held my scarf to my mouth. Sometimes I didn’t. At the automated kiosk, I ticked through yes-no health questions about fever and cough. No one screened me in person for symptoms. When the plane boarded, there were just three other passengers.

It could have been harder. It seemed like it should have been harder. I travelled while most of the world sheltered at home. Views of the Rocky Mountains, the Great Basin, the Sierra Nevada, the Central Valley, the Coast Range, all different than when I had left. Cities and towns were blanketed in fear and pain that were invisible until I looked around inside the empty plane.

At the airport in San Francisco, the flushed relief of reunion with Aaron—face to face, no pixelated simulacrum. Then abruptly, the reckoning. Was it safe to hug? How long before we could kiss? It sunk in, as we stepped back from each other, that I wasn’t really home yet. Sloppy though we were in that first moment—we did hug, we did ride together in the car, no masks—I started to comprehend what it meant that touch itself, physical closeness, was now the most dangerous thing. That I’d need to shelter myself from intimacy. Not just sex, but the ordinary contact of sharing a home. Setting the table together. Using the same hand towel. Sleeping in the same bed.

It was a terrifying calculus of conditionals. If Aaron already carried the virus—if he passed it to me—but if I’d been exposed on my trip—

I tried to absorb the scope and intensity by latching onto details from the news.

Early April.

100 cases at a San Francisco homeless shelter.

Over 30 million jobless in the US—just the ones who qualified for benefits, the ones who hadn’t yet completely fallen through the cracks.

In New York, up to 1,000 deaths per day.

And the eerie calm. The transition to stay-at-home was strangely painless. A relief even, from the compulsion to be out in the world, wringing the richest flavors from it. I had a cupboard of grains and beans, I was used to cooking simple pantry meals. I’d been working from home for years. When I’m done with my wage work, I spend much of my time alone on my creative work, writing and making art. My favorite kind of exercise is taking long walks, alone or with the dog.

Late April.

Over a million confirmed cases in the US.

Federal prisons report the first deaths of the incarcerated. Many more are expected.

I’ve been home for over a month now. Neither Aaron or I have shown any symptoms, we haven’t interacted closely with anyone else, so we’ve decided that our dyad is a safe zone. That as long as we keep up with the masks and the six-foot moats of social space when we’re out among others, we can relax at home. Except when we think about how permeable home is. What about the grocery bags? What about the mail? Should I sanitize the car door handles? Did I just chew my nail?

And beyond the physical risk is a deeper discovery, about the way fear seeps into the delicate workings of intimacy. For me this has meant discovering the protective bullet casing that I’d put on during my trip. It’s a common mode for me, going it alone, getting self-reliant. It kept me going as I traveled, moving ahead as gates swung shut behind me. Tucked in on myself like I was riding a bobsled. And that tight tuck is hard to get out of, even now that I’m standing on level ground. It can be hard to remember that someone else is here, has been here, leaning with me in this sled as we balance and steer and try to avoid a crash.

Early May.

Photo of a New York City funeral home, rows of plain cardboard coffins lined up like refrigerator boxes laid on their backs, each one tied with a black ribbon, HEAD in large letters at one end.

PLEASE TOUCH, I wrote in block letters in a previous life, when I imagined intimacy and vulnerability as tools for change. Now that vulnerability has changed in ways we couldn’t have imagined, it seems that intimacy has to change too. Hesitantly, lightly, trying to let go of what doesn’t work from before, trying to reach for what is now.

A few weeks after I got home, I finished untangling the skein of yarn. During a couple of evenings after dinner while Aaron was on his laptop, during my online work meetings when I didn’t have to be on camera, I teased out the thread and rolled it, and gradually the ball got bigger. When it seemed like I was about halfway done, I thought I’d take a picture of the ball and the tangle and call it Order from Chaos. Then I thought, I should have been taking pictures all along, from when I first tried to roll the ball and gave up.

While I thought about that, I finished the ball. It’s the size of a grapefruit sitting on my dresser, deep rusty orange.

Mary Burger (she/they) is a writer and artist working at the intersections of perception, memory, and narration. Her books include *Sonny*, a novella of disintegration depicted through and against the Trinity atomic bomb test, and *Then Go On*, short prose works about crisis and epiphany. Recent writing is in new or forthcoming issues of the* Journal of Narrative Theory,* *La Vague, The Minute Review, Sublevel, *and* Tripwire*. They are working on a memoir about gender, class, religion, entangled family roles, and the behavior of black holes.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.