Ecocatastrophe science fiction was supposed to be a warning, not a roadmap. We need more hopeful stories of the future.

by Cat Sparks

A climate-rattled world, ravaged by extreme weather events, is now a popular backdrop for top-shelf fiction. From Booker shortlisted The New Wilderness by Diane Cook to The Coral Bones by EJ Swift, authors are exploring the dramatic possibilities of a post-apocalyptic future. There’s something decadent yet alluring about ruined landscapes littered with once grandiose, now crumbling structures – civilisation’s reset button having been well and truly punched.

Some reckon it’s no better than we deserve, but I’m not one of them.

A lifelong fan of the post-apocalypse genre, I even wrote one myself – the novel Lotus Blue, envisioning what a far-future Australia might look like if we don’t take the climate crisis seriously.

But it’s starting to feel like climate fiction itself might be losing its ‘fiction’ credentials. The last few years have been a lurid montage of shifting weather patterns as greenhouse gas pollution overheats the atmosphere. Wet places getting wetter. Melting snow and swelling oceans. Strong winds that knock over great swathes of forests, flash floods, devastating droughts, hazy orange skies from megafires, suffocating urban ‘heat islands’ and washed-out roads.

‘There were simply no cities, no books, agriculture or domesticated animals on this planet the last time the temperature was so high,’ Copernicus director Carlo Buontempo said in January as he announced that average global temperatures were the highest recorded since 1850.

And yet, despite increasing climate impacts and growing calls to phase out fossil fuels, 2024 kicks off into a world where oil, gas and coal production continues to expand. In my country, Australia, the Labor government has over 100 new coal and gas projects slated for approval – this from the more ‘progressive’ of the two major parties.

If we persist on burning fossil fuels and opening up new mines in the face of decades of dire warnings, might we be returning to this civilisation-free state mentioned much sooner than anyone wants to believe?

Warnings haven’t just come from scientists or the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s weighty tomes. Ecocatastrophe has long been a trope of science fiction. Jules Verne’s 1889 novel The Purchase of the North Pole imagined climate change via employment of a giant gun tilting Earth’s axis in the hope of accessing North Pole coal deposits – a stunt only marginally more ludicrous than fracking.

More recently, Australian novels like Children of Tomorrow by J R Burgmann (2023) and The Glad Shout by Alice Robinson (2019) have shown the consequences for this country if we fail to act on climate change with the speed and scale required.

End of the world narratives like these were supposed to immunise readers against taking civilisation and its comforts for granted, so why isn’t our society swerving to avoid the hellscapes so vividly described?

Could it be that after 12,000 years of settled Holocene storytelling, all we know how to do is sit back and watch? No longer cautionary tales, ubiquitous post-apocalypse scenarios embed themselves in the cultural psyche as first-person shooter fantasies. Zombies and other monstrous infected offer distraction from the hardship of scratching survival from blighted soil. But who are the zombies really as we stand by idly watching our governments double down on fossil fuel production, ignoring the grip the fossil fuel industry has on our democracy?

Civilisation is all about communication – complex language, and the ability it gives us to co-ordinate on a vast scale, is the superpower of the human species. And yet while the technology exists to solve the climate crisis, words and stories are failing to drive enough people to action on this critical issue.

It’s time for the creators of these stories – myself included – to try a new approach. We need to move away from pessimistic apocalypse-porn and do the difficult but important work of imagining credible solutions. Optimism is often dismissed as flimsy and insubstantial, overwritten by cynicism – the easy default, worn as a form of armour: I’m not dumb enough to fall for that one. But isn’t this the greatest imaginative act of all – to envision a better future for the species?

We need more stories focused on collective responses, not an isolated hero battling for survival. Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Minister for the Future is one example of popular climate fiction that unpacks the complexities and strategies required to bring about global systemic change.

Science fiction is an inherently hopeful genre, presuming some form of inhabitable tomorrow will exist. But unless authors like myself eschew the easy thrills of the end-of-days adventure novel, we aren’t offering a blueprint to a better world, just reinforcing a blinkered, self-fulfilling prophecy about humans being too selfish and stupid to save themselves.

That might make for an entertaining climax, but it’s not one I want to live through.

Cat Sparks is an award-winning author based in Canberra. She has a PhD in climate fiction from Curtin University and was previously fiction editor of Cosmos Magazine.

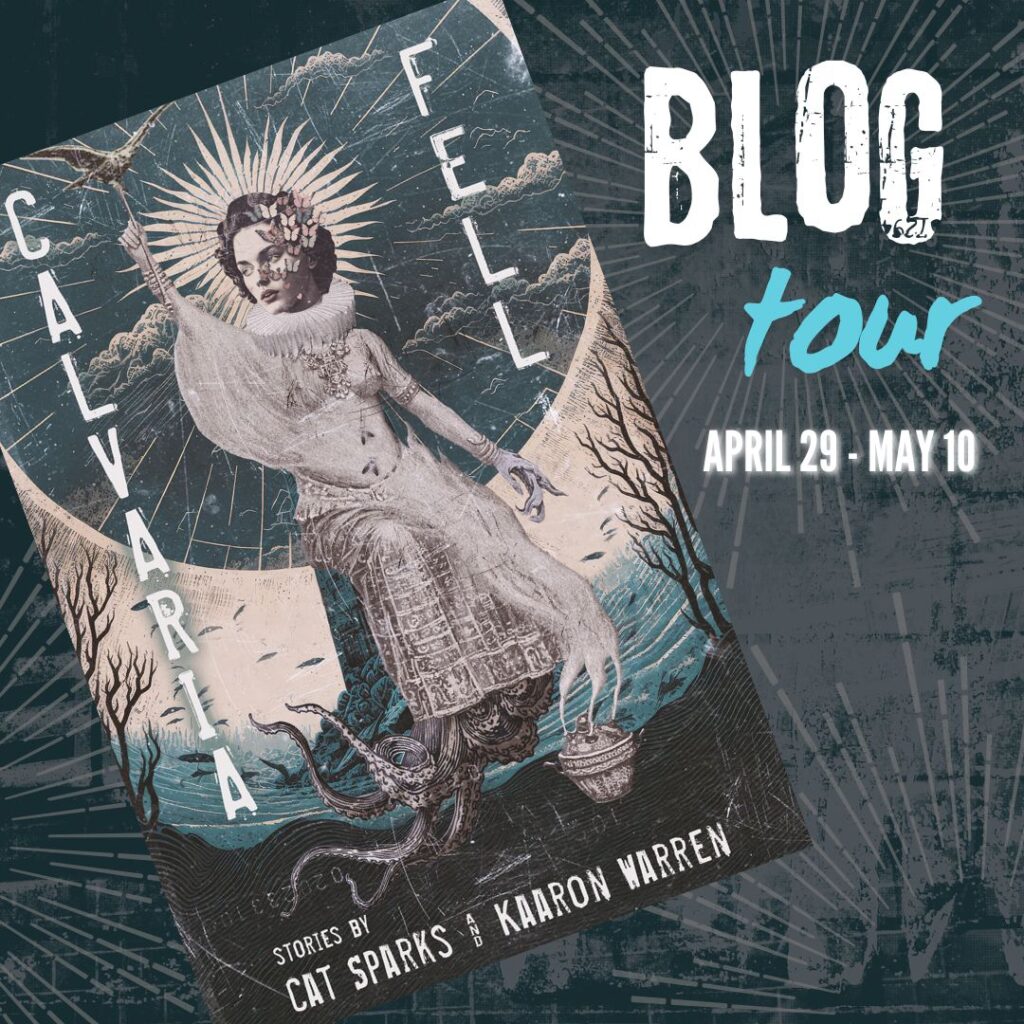

This essay is part of the blog tour for Kaaron Warren and Cat Sparks’s collaborative collection Calvaria Fell, published by Meerkat Press. You can also enter to win a $25 gift card from Meerkat Press as part of the tour.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.