Deep Blue

by Martha Anne Toll

1963. Katya detoured to St. Patrick’s Cathedral before ballet company class. Not to attend Mass—she didn’t need to mouth words and hymns that punctuated her childhood—but for sanctuary and anonymity.

Genuflecting before she started down the great center aisle, Katya took a pew on the left toward the altar, where she could avoid Fifth Avenue’s street noise and bathe in the rainbow of colors refracted through rows of stained-glass windows. She felt alone in the cavernous space, less a child of her parents than an autonomous woman. St. Patrick’s bore no resemblance to the small parish church of her childhood. It wasn’t Mama that Katya recalled from church, it was Mama’s absence, her early death, as much a part Sundays as the colorless windows over the pews.

Sound burst from the cathedral organ, as if the gate to paradise had been flung open. Massive chords streamed from above, filling the cathedral as surely as light from the stained-glass windows. The organist began practicing the same few phrases; the nave sufficiently empty that Katya could hear him turning his sheet music back to start a section over again and again; not so different from the discipline of barre work, Katya thought.

She leaned against the wooden pew. What was she doing with John? Kissing him! What was she playing at?

How could she not have disclosed her relationship with Mr. Yanakov? Mr. Y was her choreographer. He had molded her, shaped her into his Prima Ballerina. She was his muse, his collaborator, his bedmate. Theirs was more than a relationship; it was a way of life.

Mr. Yanakov was shorter than Katya. When he kissed her, she experienced the fire and brimstone that were creativity’s underbelly. In the studio he pushed her to her limits and beyond, stretching her legs, bending her torso, hovering over her on the floor. It wasn’t often that he kissed her. It was rare, in fact.

Whereas John.

He was tall but not imposing. So natural, as if they fit.

With Mr. Yanakov, she tested steps that might cohere, but might just as easily be the fleeting offspring of their charged partnership. On good days, they were a flowing, dancing stream. When Katya and Mr. Y were fully synchronized, the mirrors bounced two reflections: Katya’s, and a second that was her outline, waiting to be sketched in.

Whereas John.

His asked questions aimed at the heart of things. He wanted to know her, not an object of his invention.

Mr. Yanakov’s mind catapulted ahead and simultaneously reversed, scooping up—what? His past? She knew so little about it and didn’t share hers. He never inquired, as if she hadn’t existed before he rechristened her Katya Symanova from Katherine Sillman.

Whereas John.

All they’d done was talk—about her, about him. About their families—skirting over pain, while acknowledging it too. For he gave off an immensity of caring. In an Olympian feat, he had converted the horrors of his experience—he had entertained the Kommandant, survived because his mother pushed him toward the SS guard, saying he could sing—while she and baby Max went to the gas chambers.

John was a fountain of goodness. He had taken her on the Circle Line, the water slapping against the boat while they enjoyed Manhattan’s skyline together. He’d smiled at her delight, leaned across the table at Le Ballon Français, his attentiveness like light.

Mr. Yanakov’s furious energy ignited his couplings with Katya, which were not preceded by tender kisses or idle banter but by the relentlessness that characterized their art.

Then again. There was something more between John and Katya than talk, and it wasn’t only their kiss. (That glorious kiss, as if he had found all of her!) It was her certainty that when John watched her dance, he received the messages she transmitted. It was her dancing, her work, no matter what the critics said; her choreography was embedded in every piece that bore Mr. Yanakov’s signature.

And yet. Mr. Yanakov’s ballets were emblazoned on her limbs. Even if she couldn’t trust him, she owed him fealty. He had spurred her to excellence, summoned her inside his creative process, insisted on a dedication to their art that matched his. Trained her body, made his ballets on her, and given her the stage. Together they innovated movement.

Sweet Jesus. Boris Yanakov was that much to her.

The organist paused, pulled out all the stops, and struck a monumental chord. His pedaling reverberated throughout the cathedral, joyous and celebratory.

Katya and John had had conversations different from any she’d experienced, as if she were part of a couple like ones she’d jealously observed, who shared a friendship, who confided in each other with the regularity of morning dew. Conversation as pleasurable as melting into a penché, as exciting as a grand jeté knifing the stage. John was affectionate and serious. He had journeyed through hell and back again.

Arpeggios spilled over the balcony, looping and intertwining, traveling the keyboard; music aimed toward God. If only she could have time with John. She gazed at the gilded sanctuary before her—fluted stone columns fanning out like the corps extending developés in unison; the windows above, such a deep blue, she was convinced they contained an essential truth. Here was one she understood: she could pretend to linger over dinner, or at the door to her apartment building, but Boris Yanakov—not her grueling schedule or the exigent demands she placed on her body—rendered any contact with John a lie.

The thought of meeting Mr. Yanakov at the end of his trip abroad shot peppery fear through her. She may be in a vaunted position with the great man, but he owned her name and her future. To see John was injudicious and wrong. Mr. Y was her means to dance. She needed dance in order to be.

She bent down on the red kneeler, her head pressed against folded hands.

In John’s arms, a belonging.

❖ ❖ ❖

After class, Katya peeled off her leg warmers and stuffed them into her bag. “You look like the cat that ate the canary,” Maya said, throwing a dress over her leotard.

“Shh.”

“You’re a blushing teenager.”

“Don’t tease me. He’s too special for that.” They picked up their bags and walked outside. “We’re meeting for a picnic dinner in Central Park.”

“Cute. Will you please unload Boris the Dictator?”

“Maya!”

“Now’s your chance to hotfoot it out of here.”

“I’d never dance again,” Katya said.

“Are you insane?” They crossed the street and headed north on Sixth Avenue. “You could work anywhere.”

Work was sitting at a typewriter in an office, like Aunt Mary. Or Daddy’s dreary accounting practice—days succeeding days like drips from a rusty tap. The studio, on the other hand, was sacred space. Sinking into pliés was reciting a favorite prayer. Katya’s calling was to channel heat during floor combinations, to irradiate patterns from invisible ink—generating movement that only she and Mr. Y could see. If the fiery surge Katya felt when she leapt onstage was work, then she wanted to work forever.

“They’d hire you in London or Paris in a heartbeat,” Maya said.

“I don’t want to go to London or Paris.”

“Fine, how about Copenhagen? Or San Francisco? They have a company.”

“Too far from my dad.”

Maya stopped at the corner of 59th and Columbus and faced Katya. “What is the matter with you? It’s this guy, isn’t it?”

“I don’t even know him.”

“I can see it in your face. You’re head over heels.”

Katya couldn’t bear to hear her say it. What was she going to do? “I have to be able to make ballets.”

“Oh for heaven’s sake. The amount of fourteen-carat ding-dongs I’ve gone out with—you haven’t heard the half of it. I’d kill for a good man. If this guy is for real, you’re crazy to let him go. What about love?”

Katya shrugged her shoulders. “I can’t think about it.” Wasn’t love as fluffy as pink cotton candy? What about trust and reliability? (She couldn’t trust Mr. Yanakov.) What about the reliability of her own body? She would age—it would age—and then what? “Aunt Mary says you can only trust yourself,” Katya said, without much conviction.

“Don’t get all romantic on me. We wouldn’t want that. My parents can’t shut up about me finding a husband. They act like two lovebirds who found their perfect mate,” Maya said. “God knows, they’re not perfect. But still. There’s so much drudgery in what we do. Wouldn’t you rather settle down? Let yourself go, eat what and when you want? Stop hurting? Sleep in or go to the movies?”

“Not really,” Katya said.

What if Maya was right? What if Katya was head over heels?

Maya sighed. “See you tomorrow.” She turned west on 59th. “Don’t be stupid,” she said, calling to Katya over her shoulder.

❖ ❖ ❖

The evening was balmy. Katya lay next to John on a blanket. “Is it too early to see a star?”

“Let’s stay until we do,” John said.

“We’ll see one even in New York?”

“With you here? I think so.” He reached over and held her hand.

He felt warm and cool at the same time.

“I brought a bottle of wine,” he said. “Shall I open it?”

“No,” she said, too firmly. “I mean no, thank you, not for me. I don’t drink.”

“Not good for your profession?”

“No. Well, yes, that’s true.”

“I’ve upset you,” he said, propping himself up on his elbow and looking at her tenderly. “I’m sorry.”

No one spoke with such caring. “It’s a beautiful evening,” she said.

He brushed the back of his hand down her cheek.

She touched her cheek where his hand had been, feeling soothed even though she hadn’t known she needed soothing. “I avoid alcohol,” she said. “There’s no reason you would know,” she added. “My mother drank.” She couldn’t—didn’t want—to leave it unsaid.

“Ah. No wonder. I should have been more thoughtful. Especially as a psychiatrist. I’m trained to listen.”

“I’ve never met anyone as thoughtful as you.” He was haloed in compassion. “My mother was drunk when she was killed.” It felt urgent to share her deepest confidences, as if intimacy with John was preordained. “She was hit by a truck crossing Northern Boulevard. I was seven, a little girl on the jungle gym when Aunt Mary came running across the playground at recess. I could tell something was terribly wrong.” She rubbed her stomach to dissipate the sick, twisty feeling at the recollection.

“How awful,” John said, gazing at her as if she was all that mattered. “That’s an abandonment in more ways than one.”

“An abandonment.” How did he know? “It makes everything worse, doesn’t it? Much less benign than a regular accident, not that that’s benign. I was fifteen when Daddy started talking about Mama’s drinking. I had no memory of it. It was like she died a second time. As if she left me on purpose.”

“No one would leave you on purpose,” John said.

“I don’t think that’s true,” Katya said, anguished over the searing reality of her choreographer, who had declined to invite her to his guest appearances in Europe.

What about the man beside her? What was she going to do?

“Heartbreaking,” John said, wrapping her in a full embrace.

“It changed me when I found out,” Katya said, her face in his chest, clutching his shirtsleeve as if it were a life preserver. “Made me feel like I couldn’t rely on anyone.”

“I can’t stand that,” he said, holding her tighter.

“Daddy blames himself. He says if he’d been paying attention, he could have stopped her.”

“It’s an illness,” John said. “Drinking.”

Katya looked up at him.

“That’s the latest science. Illnesses are not something we can control,” he said.

Was he sent to deliver mercy? “That would put it in a different light. Very different.”

She turned toward the sky. “Look! A star!”

“What did I tell you?” he said, leaning over to kiss her.

Martha Anne Toll‘s debut novel, THREE MUSES, won the Petrichor Prize for Finely Crafted Fiction and is forthcoming September 2022. “Deep Blue” is an excerpt from THREE MUSES. Please visit Martha at www.marthaannetoll.com and tweet to her @marthaannetoll.

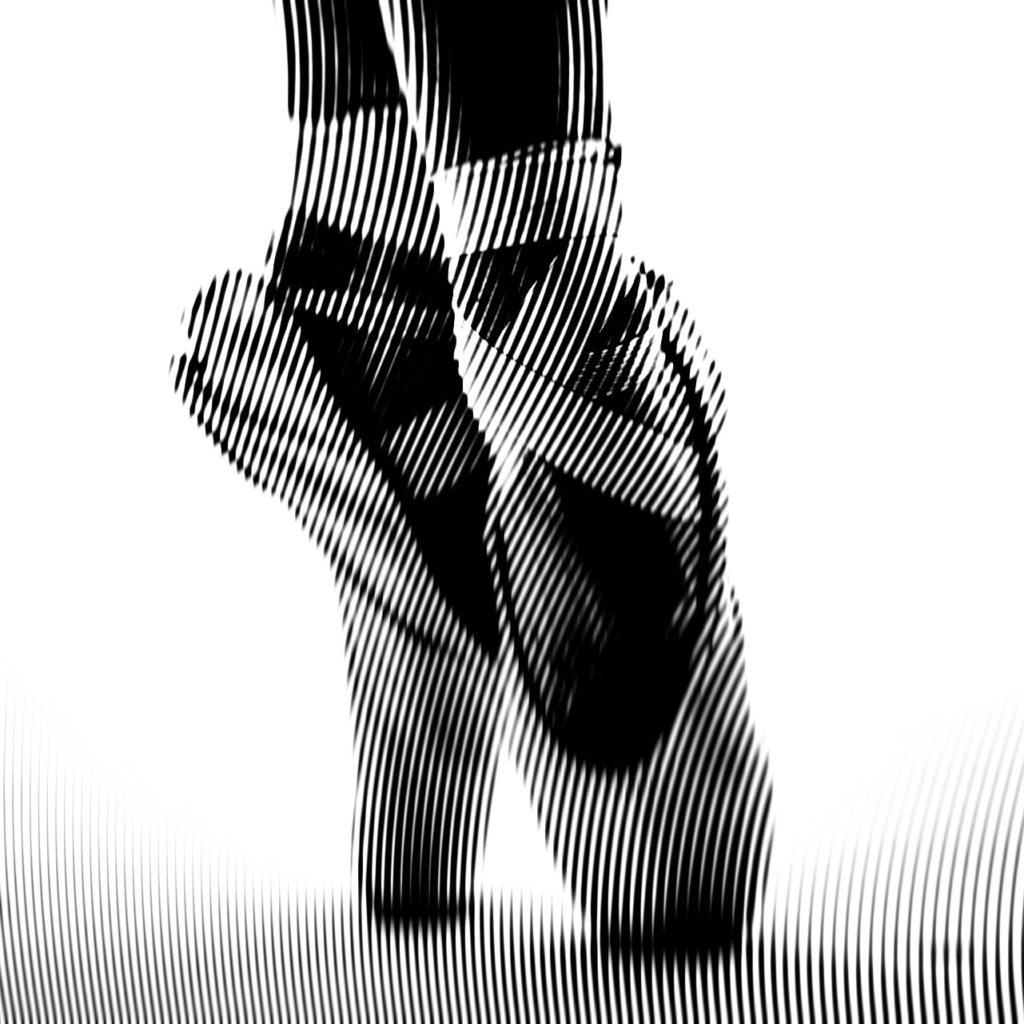

Image: Nihal Demirci/Unsplash

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.