Early in John Brandon’s fourth novel, Ivory Shoals—a spirited remaking of the prodigal-son parable set in the American South during the final days of the Civil War—twelve-year-old Gussie Dwyer has come to collect the savings his recently deceased mother, Lavina, entrusted with her long-time employer, Rye. Rye delays this encounter, leaving the boy to wait awkwardly in the barroom, a foreign space reserved for hardened men and the working women looking to entertain them. Out of economic desperation, Lavina had turned to prostitution to support her family.

Here’s this kid—an orphan, trying to get what’s owed to him from a man whose living comes from profiting off the vices of others, money his mother earned so that he might survive. In over his head, Gussie relies on the wits his mother instilled in him: “to be sparing of those deemed vile and leery of angels.” Of course, Rye concocts fabricated expenses Lavina owed, leaving nothing but a meager couple of coins to impart. Satisfied with cheating an orphan, Rye assumes their business complete; he doesn’t believe Gussie has the gumption to do anything more. Rye will not be the last adult who learns underestimating Gussie can be a costly error.

Cut from the same cloth as Portis’s Mattie Ross and Twain’s Huck Finn, Gussie shares their emotional fortitude and resilient psyche. Like the young misfits that populate Brandon’s previous work, Gussie is forced to navigate an adult world with little guidance. With Ivory Shoals, Brandon successfully combines a coming-of-age adventure tale with a complex study of class and honor, all while reimagining a classic story of redemption.

The structure of Gussie’s trek falls into familiar episodic patterns of hardship, hunger, and periods of loneliness. Yet Gussie never loses his hopes of improving his situation. The only clue he has to his paternal lineage is a forgotten pocket watch left behind after a brief affair. The eighteen-carat gold, rear-winding Waltham pocket watch engraved with the initials “M.J.S.” belongs to Madden Joseph Searle, a prominent inventor who, after his tryst with Gussie’s mother, returned to his home and unhappy family life on the eastern coast of Florida. Gussie writes a letter to Searle, informing him of his plans to meet him, his only living relative, and return the watch. Meanwhile, as his arrival there grows ever more imminent, domestic strife is building in his father’s house.

The Searle family fortune divides loyalties and fosters resentments. Although Searle still cherishes his time with Lavina, he has no idea he has another son. Searle has made his fortune in air-cooling, but he’s also put more into his pursuits of the mind than strengthening his familial bonds. His long-estranged wife left Searles and their son Julius to each other’s company. The two continue to strive for common ground only to grow farther apart as the years pass. When Gussie’s letter arrives, it’s intercepted and read with skepticism by Abraham, Searle’s most trusted servant and Julius’s companion. Concerned that his employer’s penchant for generosity is going to get him in trouble again, Abraham concludes something worse. Although Gussie has stated no interest in Searle’s money, he remains a potential heir— “A divider of inheritance. A mouth to feed and brain to school and overall deflator of wealth.” Gussie also represents something even more divisive: the son Searle always wanted, an engaged, inquisitive boy whose affections aren’t conditioned or rooted in entitlement.

Even for a man of Searle’s prodigious gifts, his accumulated capital provides a study in the consequences of amassing great wealth. While Gussie may be a bastard, witnessing the hardships Lavina endured while raising him in poverty has nurtured compassion in him. Meanwhile, despite their differences, Julius has stayed with his father because, even when he was young, he understood his father’s wealth afforded him comfort even if it deprived him of affection. Searle disdains the traits Julius has developed and sees service to the Confederacy as an opportunity for him to build character: “Searle had not been able to accept raising a coward, had not wanted an idle fop the carrier of his bloodline, and might now, as a result, have no son at all.”

So, instead of using his influence and connections to keep his son from going to war, Searle shielded Abraham instead. Abraham— the product of neglectful parents—has exchanged a lifetime of servitude for an existence far more comfortable than the squalor he knew growing up. The family hired Abraham because Searle’s then-wife demanded a live-in-staff, much to her husband’s embarrassment. While Abraham faces no financial hardship, and avoided serving in the war, he has no agency—his only concerns are his employer’s. “He’d rather be mean than weak. Would rather make his own fortune than continue tending another’s.” Only upon Searle’s death will Abraham’s service end; with Julius in charge of the estate, he might regain personhood. Abraham stays in correspondence with Julius as much out of affection for the young man as self-interest. He encourages Julius to return home from exile, where he has eluded military service living in excess, resenting his father while anticipating his inheritance.

[Searle] knew Julius was alive and most likely uninjured. Uninjured bodily, yes, but Searle’s fear was that the boy, no boy but a young man now, was so stung of soul by his father’s sending him off to war—a milieu that so grossly ill-suited him, a punishment for being the person God and Ruth Purifoy had made him—that he’d never show himself at the estate again.

Unbeknownst to anyone save his beleaguered lawyer, Searle has kept secret the threat of an impending lawsuit brought on by the family of his long-dead former mentor, whose name was attached to many groundwork patents associated with the air-conditioning machines they developed. In Searle’s penchant for ignoring family matters while never losing focus on his work, he never considered that expanding on his mentor’s ideas would constitute legal infringement. The prospective lawsuit could drain his fortune, forcing him to sell his estate to “settle the damages,” according to the aggrieved party. Like his son Julius, Searle has failed to see his vast wealth as finite or imagine the potential for upending life changes until they arrive on his doorstep in the person of Gussie.

A stylized departure from his previous works, Brandon embraces the flourishes of 19th century vernacular and period details while effortlessly blending them with the familiar themes of Gussie’s growth while on the road. Brandon has a knack for putting his young characters in situations they’re unprepared for, taking on oversized roles, squaring up against conflicts only to slowly realize they’re out of their depth and in over their heads. Flailing only to finally rise to the occasion, these characters are the primary source of the enormous heart and riotous humor that distinguish his fiction. Long-time fans of Brandon will relish this raucous yet moving road novel even as resolutions come too quickly. Although Gussie’s journey tested the beliefs Lavina instilled and the hard-won wisdom he gained along the way, Brandon leaves the reader with vicarious parental anxiety: will Lavina’s lasting influence be enough to guide Gussie into adulthood if Searle can’t provide the type of environment to help him thrive? We feel the uncertainty that no doubt plagued Lavina on her death bed, as she considered the future instore for the good-hearted Gussie left to fend for himself. Is this kid prepared for the world?

Like many of us old enough, Brandon understands the real peril of the coming of age story, is it never ends. No matter the stage of life, we wonder if we have enough grit to maneuver the twists and trials the adult world throws our way.

***

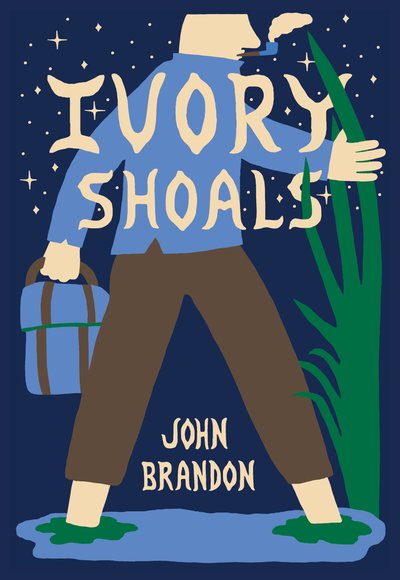

Ivory Shoals

by John Brandon

McSweeney’s; 256 p.

Tim Hennessy is a bookseller who lives in Milwaukee, WI. His writing appeared in Publishers Weekly, Tough, Mystery Tribune, Midwestern Gothic, Crimespree Magazine, and the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, among other venues. He edited the Milwaukee Noir anthology from Akashic Books and is the fiction editor at Tough.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.